Youth, youth, springtime of beauty.

—Anthem of the National Fascist Party, 1924Blaming the Parents

J. Edgar Hoover puts teens in time out.

This country is in deadly peril. We can win this war and still lose freedom for all in America. For a creeping rot of moral disintegration is eating into our nation.

I am not easily shocked nor easily alarmed. But today, like thousands of others, I am both shocked and alarmed. The arrests of teenage boys and girls all over the country are staggering. Some of the crimes youngsters are committing are almost unspeakable. Prostitution, murder, rape. These are ugly words. But it is an ugly situation. If we are to correct it, we must face it.

You read in the news columns of the most flagrant cases. The sordid movie-theater gang assault in New York. The vicious railroad-track murder in Houston. The tragic case in Michigan of the sixteen-year-old boy who killed his little sister after unmentionable cruelties.

These are not isolated horrors from another world. They are danger signals which every parent—every responsible American should heed. These are symptoms—of a condition which threatens to develop a new “lost generation,” more hopelessly lost than any that has gone before.

Consider: in the last year, 17 percent more boys under twenty-one were arrested for assault than the year before, 26 percent more for disorderly conduct, 30 percent more for drunkenness, 10 percent more for rape. And that despite the fact that many of this age group had already gone to war or were productively employed. For girls, the figures are even more startling: 39 percent more for drunkenness, 64 percent more for prostitution, 69 percent more for disorderly conduct, 124 percent more for vagrancy.

And these were only the ones who were arrested—the advanced cases.

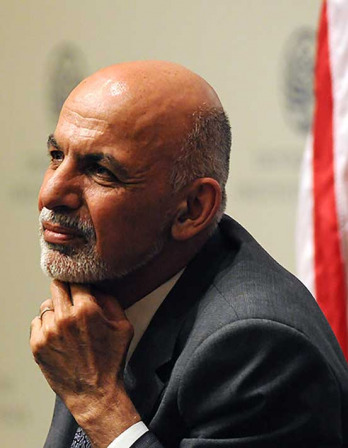

Thin Mints, by Julie Blackmon, 2014. Archival pigment print. © Julie Blackmon, 2014, courtesy of the artist and Robert Klein Gallery.

The other day a friend of mine, who is a police chief, saw a fifteen-year-old girl coming out of a tavern. She had obviously been drinking. The chief knew her, and knew her family—respectable, serious-minded people. Shocked, he took the girl home to her mother. He told me about it as an example of how even the best homes are being hit.

But to me, the rest of his story was even more significant. He had expected the child’s mother to be upset, and she was—but not in the way that he had expected. She was upset because of the indignity he had inflicted on the girl by bringing her home. Of course the girl had done wrong, she admitted; but she should have been allowed to look out for herself. That, the mother insisted, was the way to develop a child’s character.

And that, I insist, is the kind of crackpot theory which has laid the groundwork for our present surge of teenage trouble. For years, we have listened to some quack theorists and pseudopsychologists who have preached that discipline and control were bad for children—that they should be left uninhibited to work out their own life patterns, their own self-discipline. But you don’t acquire self-discipline if you never learn what discipline is: neither can life’s problems be worked out without experience which can be secured only through hard knocks or by guidance from the experience of others.

Now we are reaping the harvest. Fathers have gone to war or are working long hours. Many mothers, too, are working on day or night shifts. The youngsters are left to their own devices. And the tragic fallacy of the theory that self-discipline “just grows” is being demonstrated day by day.

Our FBI fingerprint files are full of the proof. Here is a case that is sickeningly typical: two girls, one fourteen, the other fifteen. Fathers in the army, mothers working in war plants. Left to themselves, they stroll the streets, get picked up by two boys, and are finally apprehended halfway across the continent in a stolen car.

Here is a boy whose mother is dead and whose father is so busy with his war job that he doesn’t bother with him. The boy sees something in a five-and-ten that appeals to him and steals it. He falls in with another youngster and breaks into a filling station. Then they get bigger ideas. They put an eighty-pound angle-iron across a railroad track, thinking to loot the wrecked train. Fortunately, somebody catches them in the act, and there is no wreck—except the wreckage of that boy’s life.

These are typical, everyday cases. They could have happened any time, because there always have been neglected children, unguided children, undisciplined children. The point is that such cases are multiplying to a point of crisis. It is time we asked ourselves: is this a wholesale breakdown in discipline?

The war greatly aggravates the situation—the unsettled homes, the confusion and the restlessness, the “last-fling” philosophy. Two boys and two girls go into a tavern and get some drinks. They get to talking about the big money to be made in the war plants in the city a hundred miles away. Why stay cooped up in this one-horse town? One of the boys gets a revolver; they steal a car and are on the way. They are finally caught only after a running gun battle.

I have heard people speak of young girls as being overenamored of uniforms. Too many are. And again, the consequences are often tragic.

Here is a sixteen-year-old girl who falls in love with a soldier. He is transferred. She starts running around with other men in uniform, then ends up in a house of ill fame.

That is a common progression—so common that it is adding up to a major tragedy.

And here is the more violent type of progression. A girl quits going to school and Sunday school, begins going to dives. She gets coarse and vulgar, while her parents stand by and do nothing, and when a policeman attempts to reason with her, she throws a brick at him. She is sent to a training school, then released. Within a few weeks she is back in the hands of the law again, for picking up men and blackjacking them.

Another effect of the war, of course, is that it is making it possible for many youngsters to earn more money than ever before. For youngsters who have been trained in no higher motives than self-gratification, that is merely an opportunity for loose living. Count the cheap places of entertainment in your neighborhood and study the ages of the customers if you doubt it.

I am not blaming the youngsters. I am trying, very definitely, to do exactly the opposite—to put the blame, where it belongs, on my own generation, which has failed in its responsibility to its children. We failed in the years before the war, in

that we let discipline slide, some deliberately as a matter of “theory,” the rest of us thoughtlessly because it was the trend of the times.

Obviously, wartime conditions call for extra guidance, extra control, extra discipline. Parents should take stock of the discipline—or the lack of it—in their families, and consider how it might be improved or tightened up. They should follow definite rules as to what young people may do, where they may go, and when—determined by the standard of whether or not it is good for the child. They should insist on obedience, and not shy away from penalties for wrongdoing. Children may not like it, any more than soldiers do, but it is the one way to make sure that both will react correctly in moments of decision and danger.

The average parent, I am convinced, is too easily overwhelmed by that old argument that “all the other kids are allowed to do it.” Somebody has to draw the line somewhere, or this justification can spread out like a chain letter. Of course different parents have different ideas about what their children should be allowed to do, but it is time that parents began to find some definite lines on which to unite.

We are fighting a war to establish the Four Freedoms for the generation now coming to maturity. We had better make sure that they have the self-discipline to live in a free world.

J. Edgar Hoover

From “Youth…Running Wild.” At the age of twenty-four in 1919, Hoover headed the Radical Division in the Justice Department, overseeing the Palmer raids that cracked down on supposed foreign subversives. In 1924 he became the director of the Bureau of Investigation, later renamed the FBI. In the 1950s, Hoover helped secure the conviction and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, developed COINTELPRO, and published Masters of Deceit: What the Communist Bosses Are Doing Now to Bring America to Its Knees.