A garden must be looked into, and dressed as the body.

—George Herbert, 1640Funhouse Goddess

It has never been easy to decipher what nature is trying to tell us, but that hasn’t stopped us from filling in the blanks. A look at the sexual politics of natural law theories.

By D. Graham Burnett

The Empire of Flora, by Nicolas Poussin, 1631. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany.

Nature has a way of showing up unannounced. And I don’t just mean those episodic depredations of storm and flood, or even that field mouse you found in the pantry of the beach house this spring—the one that had chewed its way through the top of the olive oil bottle to die in panicked ecstasy, treading the golden elixir into an extra virgin froth. No, I mean sometimes Nature actually shows up, as in: Poof! There she is.

Take the story of

Alain de Lille, who was wandering along one fine day in the twelfth century muttering to himself about Ovid, when, suddenly, down from the sky sweeps a crazy crystal chariot drawn by celestial doves and bearing a towering, magnificent maiden queen. Around her head whirl the very stars and planets, and upon her billowing robes an overcome Alain seems to see the medieval equivalent of an IMAX nature documentary: over there, on the scrim of her diaphanous cloak, a montage of the bird kingdom, where falcons wheel and clip herons in midflight, and ostriches roam over desert sands; over here, on her seamless mantle, some Jacques Cousteau–style footage of whales disporting themselves in the deep, escorted by dolphins and a host of finny friends; and finally, on the linen tunic gathered up against her shapely body, a drive-in movie of life upon the terrestrial earth, where lions and tigers stalk their jungle prey, nervous rabbits bound along a hedge, and graceful deer graze upon the dales.

As this cosmological funhouse goddess—Natura—drops to his side, Alain swoons in queasy terror; but just before he blacks out and face-plants at her feet, he finds himself momentarily fantasizing about the hidden picture show probably playing on her panties. Typical. That’s a defrocked monk for you.

Not that it was a totally unreasonable fantasy—after all, who could miss that gaping tear right down the middle of her dress?

Thus begins one of the great phantasmagorical allegories of the Western canon, De Planctu Naturae, or The Plaint of Nature, a text that put the commandments of God on the lips of nature, whence they’d be heard murmuring for the better part of the next eight hundred years. Alain de Lille didn’t invent the idea that “nature,” rightly understood, teaches us how to live and what to do, but he gave dramatic shape and voice to this proposition, which would organize much of the intellectual life of Europe well into the nineteenth century. When nature showed up, it was generally time for a lesson—about politics, about sex, and, above all, about sexual politics.

It’s 1690—are you curious about how to arrange your government? Beehives and beaver dams offer plausible models, both stamped with the authority of the Creator—so Early Modern thinkers studied them closely as they reasoned about novel political forms (and they were very worried when they found out the “King Bee” was a Queen). By the 1770s, newly discovered Tahiti seemed like the ideal place to meet a “natural man,” who would presumably be able to instruct Enlightenment philosophes in something like “natural politics.” But then “natural woman” was so distracting! Over the next two decades, fantastical descriptions of the social and sexual practices of the island helped drive nails into the coffin of the Ancien Régime, while the Grub Street pornographers cashed in. Back in the era of Bleak House, more than one waistcoated bourgeois gentleman, smoking his pipe before a crackling coal fire, found himself musing about the moral justifications of an increasingly dog-eat-dog economy. Well, there was good news: it turns out dogs do eat dogs down on the African savannahs. Darwin’s theory of the developmental and progressive effects of deadly competition in the wild very quickly did double duty as a means of extending cosmological sanction to the weed-out abuses of late Victorian capital. Darwin had some things to say about mate selection too.

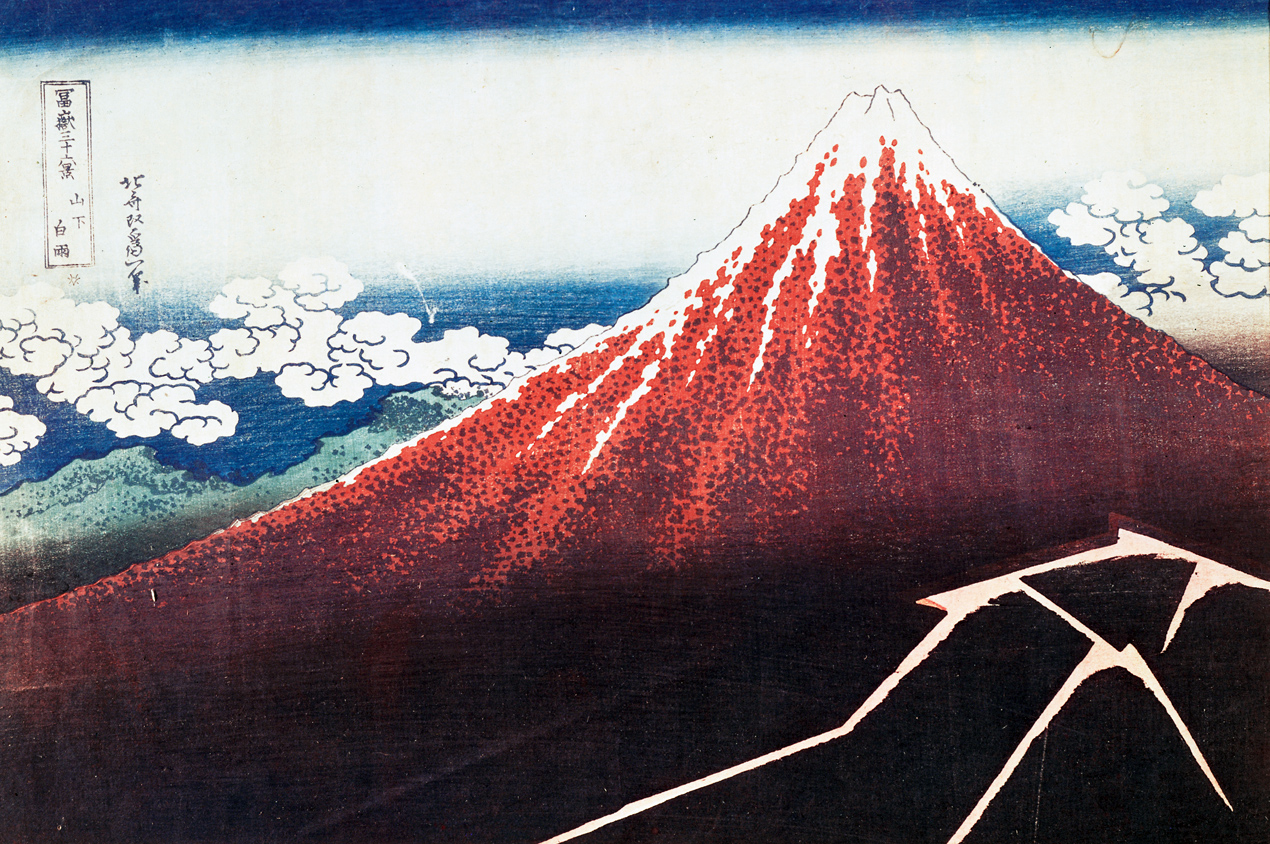

Lightning on Mount Fujiyama, by Katsushika Hokusai, c. 1823. Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois.

These ways of reasoning and arguing have never really died, despite a number of excellent arguments against them (Mill comes to mind). From the cataleptic Bible thumpers of our heartland railing against legal sanction for “unnatural” domestic arrangements, to evolutionary psychologists in Cambridge, Massachusetts, lecturing us soberly about game-theoretical models of monogamy, plenty of folks continue to think, explicitly or implicitly, that we learn the way things should be by looking at the way they are—that is, in nature. What’s nature trying to tell us? How would we know? Who’s in a position to say? These are fundamental questions that haunt the philosophical traditions of Christendom and the secular societies it has spawned. The efforts to answer them amount, in the end, to the history of science, since this is the body of practices, institutions, and instruments that evolved to hear what Alain’s psychedelic angel was saying.

Alain himself had it relatively easy: no chem lab, no calculus, no tedious hours at the microscope trying to discern the divine order inscribed in natural phenomena. All that would come later and give headaches to other students of the “Book of Nature” (which turned out to be just as hard to decipher as its equally important shelfmate, the Book of Scripture, with which it was supposed to agree). Working in the tradition of Boethius—whose Consolation of Philosophy introduced a twenty-foot woman named Philosophia and let her solve some thorny metaphysical problems directly—Alain could just bring Nature on stage, give her a face and a voice, and then listen.

In fact, he even got to smooch with her. Coming to, he finds himself in Nature’s arms, and she is kissing him on the lips and weeping. “Why so sad?” he wants to know; and, “Who tore your dress, anyway?” In reply to which Nature tells her story.

She is, she explains, the vice-regent of Almighty God, who created the whole universe, replete with diverse animals and plants, all configured in a vast system of balance and harmony. The original creation is God’s, of course, but the business of actually running the system is hers, and she is centrally responsible for ensuring continuity of form through the cycling generations of birth and decay. He made the rules, He can enforce them, and His is the empyrean realm of eternity. But here, in the created world, she is His law and minister. As she puts it to Alain, “He made me the mistress of His mint, to put the stamp on the different classes of things.”

An important post, to be sure. And this responsibility—to see to it that everything “breeds true”—seems to hearken back to the roots of the very word “nature,” which hails from the past participle of the Latin verb nasci, to be born. This deep etymological tie between the processes of birth and the whole concept of nature goes a long way toward explaining the durability and ubiquity of feminized figures of the natural world: we might say that “mother nature” is a notion that hides in the word itself.

Unfortunately for all of us, however, Alain’s (virgin mother) Nature found the work on the whole a little overwhelming and decided to enlist some helpers. And here was where things started to go seriously wrong, since this Christianized Pandora (or Olympian Eve, if you prefer) chose as her adjutant the love goddess Venus, together with that little do-gooding tyke Desire. Not a great idea. Pretty soon there was a lot of loving going on.

Which brings us to that tear in the dress. Weeping Nature has come down from on high in all her glory for the express purpose of decrying mankind’s monstrous assaults on her person: human beings’ assaults on the nature of things. A twenty-first-century reader turns the page hoping to learn about some sort of twelfth-century conservation ethic (perhaps reflecting anxieties that new agricultural techniques and urbanization were transforming the medieval environment), only to discover that Nature appears to think the “ecological” crisis of the universe, circa 1170, is that everyone is having too much sex, especially too much sex for fun, and also weird, deviant sex—why, men are even having sex with men, and then sometimes women are…. Pointing to her shredded tunic, Nature moans, “Many men arm themselves with vices, and in their violence they lay cruel hands on me, tear my clothes to ribbons which they carry off as trophies, and then they drive me, whom they should clothe in honor and reverence, stripped naked like a harlot, into a common brothel.” Human lust was destroying nature.

In Alain de Lille, the grand conflation of “is” and “ought,” of the laws of nature and the laws of God, turns out to be largely concerned with what goes on when the lights go off. This particular slip has recurred with nearly perfect reliability right down to last semester, when I had a serious and thoughtful Catholic student in my office dilating on “natural law” by means of a kind of higher hand jive. Why is it that so often when God is heard to speak through nature, He seems to be going on about our genitals? It’s difficult to believe He finds the subject so compelling.

Lest any of this seem, well, medieval, a word about where I picked up my first copy of De Planctu Naturae. Not, as it happens, in a bookstore. Rather, I plucked it from a box of trash laid out on a street corner in New Haven back in the 1990s. I have excellent evidence that this well-thumbed paperback had been discarded by our neighbor, who was in the middle of clearing out his apartment for a move. Where? To D.C., where he would be clerking on the U.S. Supreme Court in those middle years in the wilderness between Bowers v. Hardwick and Lawrence v. Texas.

Had this young Christian thrown it out because he had finished with medieval homophobia? Or because he was taking it to a higher level? There’s no way to know for sure, but “natural law” is alive and well among the conservative justices of the court. Several of them, like Alain, seem to hear Nature loud and clear, and she is still weeping. Moreover, despite the fact that most of the surface of the globe is rapidly being converted into either a strip mall or a factory to produce the things that sell in strip malls (with what look like catastrophic consequences for the global climate), she would appear, on their account, still to be weeping about men playing footsie in public lavatories.

Historians have done a great deal of work to dig up and string together the shifting iconography of Natura out of the Middle Ages, through the Renaissance, and into the Early Modern period. The story is complicated, the stemma of texts demanding, the scholarship rigorous. Moreover, vast historical changes cannot easily be epitomized by a few marginal illustrations. But for our purposes it suffices to say that Alain’s figure was on to something: Nature was stripped of her royal robes across those years, and her newly exposed body stimulated revolutionary thinking about who she was and what was to be done with her.

The Harvard historian Katherine Park has shown clearly that, by the sixteenth century, regal figurations of Nature had mostly gone the way of plainchant, replaced by pseudoclassical images of buxom nudes whose breasts (sometimes as many as a dozen) frequently drip, ooze, or spray a sustaining milk. Was this an image of power and dignity? Perhaps. Of fertility? It would seem so. And yet, that flaunted nakedness—nature au natural, as it were—was bound to give the lads ideas.

Lads like Francis Bacon. The writings of Bacon, that quasi-upstanding Jacobean prosecutor, incandescent philosophical fantasist, and obligatory Dead White Whale-Male of the Scientific Revolution, have long featured prominently on the syllabi of historians trying to explain modernity. His call for a hands-on “experimental philosophy” gave scholastic mumblers a kick in the pants, and his vision of Adamic man restored to dominance in the worldly garden (by means of science and technology) bound power and knowledge in a newly messianic-cum-practical program. That he appears to have died of a cold caught while experimenting on a frozen chicken did not tarnish his legacy, though it made him a less alluring martyr for science than, say, his rough contemporary Galileo.

Back in 1980, in an influential and controversial book entitled The Death of Nature, the feminist scholar and environmental historian Carolyn Merchant made Bacon the bogeyman of a polemical story about how nature went from being understood as a soulful, honored earth-mother to being pillaged and exploited as the slave-bitch of Anglo-European capitalism. Gendered imagery lay at the heart of the change. As Merchant would have it, Bacon performed a kind of Nietzschean “transvaluation of all values” upon the traditional image of nature. Forget the mother stuff, forget the queen stuff: she was a woman, after all, and when you go to a woman, you bring your whips. “Nature must be taken by the forelock,” Bacon wrote at one point, in an arresting passage that Merchant adduced in slam-dunk support of her argument.

And what was supposed to happen next? Bacon was pretty clear: it was the obligation of the natural philosopher to probe nature’s body, to rifle her secrets, and to make her yield him fruit. Here, that lamented assault of Alain’s De Planctu Naturae—man’s transgressive attack on Nature’s flesh—was being refigured as a veritable theory of knowledge. Modern science was born in sin, as the rape of nature.

Or so Merchant argued. Not everyone bought it. After all, Bacon personified nature a number of ways, not all female (for instance, he liked to use the goat god Pan too and did not recommend grabbing him by the hair), and in a few places it was Bacon’s English translators who had used the “she” pronouns for the feminine Latin term natura when a plain old “it” might have been more appropriate. Moreover, while it was true that Bacon used some racy language when describing how men ought to win Nature over, it wasn’t all caveman courtship: in various passages he seemed to suggest that Nature had to be wooed and persuaded. This remained an eroticized epistemology, to be sure, but it didn’t telegraph strip mining and thermonuclear weapons quite like the original Merchant thesis. And it gets even more complicated: conceding that Bacon did talk here and there about Nature in ways that to us now read distressingly like advocacy for sexual violence, several historians went on to point out that back in the seventeenth century there were a number of different ways of thinking about rape. What cretinous woodcutters did to milkmaids in the fens was not to be confused with what knights did with maidens in romances—and, more importantly, neither of these was to be confused with what the Romans did with the Sabine women. That, like the rape of Europa by Jupiter, was to be understood first and foremost as a heroic tale of nation creation—a foundational moment for a powerful people. It was more a raptus—a sort of semiconsensual kidnapping with privileges, undertaken for a “good cause”—than a garden-variety sex crime. Was Bacon invoking this sort of thing when he goaded men to take up nature in their strong arms and create a brave new world? Maybe. After all, this was the man who penned a little heroic treatise entitled The Masculine Birth of Time.

Where does this leave the Merchant thesis? If at its most extravagant, The Death of Nature represented the unlikely intersection of late-1970s Take Back the Night activism and old-fashioned intellectual history of the Scientific Revolution, the core claims of the text have nevertheless survived, and changed the way historians talk about science, nature, and gender. As Merchant put it in summary, “Sexual politics helped to structure the nature of the empirical method.” Few scholars would now disagree. Moreover, the empirical methods of science have, in return, substantially structured the sexual politics of modernity.

Nature, sex, politics, science: the true, all-time genius of this quadrilateral problematic was, improbably enough, a neurotic French traveling salesman from Besançon named Charles Fourier. Having begun with one kinky dream about natural order, I’ll end with another, since the arc from De Lille to Fourier (via Bacon) nicely traces our eccentric fantasy life with nature over the last millennium.

Fourier, who recoiled from the madness of the French Revolution into a bachelor seclusion of exuberant and paranoiac graphomania, eventually spawned, on the strength of a handful of queer pamphlets, a global cult of dizzying scope and zealotry. His followers—from the steppes of Russia to the hill country of Texas to the jungles of Brazil—swarmed together in improbable utopian communes and flirted with free love, all as part of an elaborate scientific experiment. The aim? To transform society, of course, but beyond that humble mission, to restructure the geophysics of the earth and ultimately the solar system. All it would take was good loving—and not the kind that Jesus talked about.

Fourier’s masterwork, The Theory of the Four Movements, is quite possibly the weirdest book of the nineteenth century, and arguably the most visionary. Like Alain before him, Fourier announces at the outset that Nature herself has paid him a visit:

Before me, humanity wasted several thousand years in a foolish struggle against nature; I am the first to have bent the knee before her, by studying attraction, the organ of her decrees. And she has deigned to smile upon the only mortal to have idolized her, and has revealed to me all her treasures.

Same plot, different century, it would appear. But Nature’s message to Fourier could not have been more remote from that to Alain. Where Alain’s demiurge wept that men and women could not contain their desires, into the ear of a lonely provincial Frenchman of straitened means, the shimmering goddess whispered a significant correction: she was weeping because men and women contained their desires.

Assuming a loving God who’s trying to speak through nature, it followed that our desires are His very clearest instructions. And even if they are bizarre (Fourier briefly touched on foot fetishes, dress-up fantasies, and a variety of other unconventional appetites), they must all fit together somehow in that “divine order” that the theologians had been ratcheting on about since the age of the Church Fathers. You can sort of understand Fourier to be calling their patristic bluff: “Loving God? Divine Plan? Nature as Norm? Okay, my friends, let’s try to make this work, given what we know about life down here….” In view of his answer, Fourier was either a satirist of super-Swiftian proportions or one of the most devout men ever to live. That you can’t quite decide which is testimony to his uncanny literary gifts.

To hold the ancient elements of natural theology together (a project Voltaire, Hume, and others had loudly declared absurd), Fourier sketched a world that was trying to become something very different if we would only get out of the way—of ourselves and of the operations of nature. Instead, we had created this monstrous thing known as “civilization,” in which everyone was forced to hold hands, chitchat, and go slowly bananas in a whirlpool of spiritual, material, and sexual frustration. By thus refusing to give full scope of satisfaction to our polymorphous desires, human beings had sinned mightily, were every day sinning mightily, contra naturam. And for this continuous transgression against her wishes, Nature herself was relentlessly punishing us in the grandest ways.

Cosmic ways. It was Fourier’s contention that a vast cosmological harmony pervaded the universe and that a subtle and powerful force of “attraction” organized not simply the material world (that was Newton’s theory of gravitation, which Fourier admired but thought merely the tip of the iceberg) but the entirety of the organic and social world as well. The result was countless latent correspondences, pervasive action at a distance, and the propagation of waves of dissonance that expanded outward from mankind in invisible destructive ripples. For instance, why was it that beavers—so happy in the wild—generally refused to breed in captivity? Fourier knew. Clearly, when they got near us, they could feel our miserable sex lives, and our bad vibe poisoned their amours. This basic problem could be extended from zoology right through to astronomy since planets also had reproductive cycles, which were a little like those of plants: they released spermatic pollens that mingled in outer space and seeded new galaxies. According to Fourier, our own earth (itself as depressed as those captive beavers, and for the same reason) had been for thousands of years unable to jet its luminous spray at the stars because of the pullulating presence of millions of humans, all grotesquely disregarding the palpable calls of nature.

“Conversions Seven, Urban California,” from the series "Ciphers: Decoding the Growth Machine," by Christoph Gielen, 2004. Chromogenic print, 40 x 50 inches, edition of 4. © Christoph Gielen, courtesy Jovis Verlag, Berlin.

But there was hope. If “civilization” could be destroyed; if human beings could learn to act in accordance with the natural laws of what Fourier called “passionate attraction”; if they could be configured in the social constellations for which they were intended (vast monasteries of love and work and play where everyone’s vices, properly nested among their counter-vices and all given entirely free rein, would instantly become virtues), then everything would start to line up. Literally. The axis of the planet would tilt, shifting the optimal zones of cultivation into the regions where there was more good land (after all, why, if God loved us, would He leave millions of acres of good land under the ice of Siberia?). Captive beavers would fecundate, as would the planet itself, flowering a sunny polar corona that would gently warm the whole globe to a fertile paradise. Loathsome toil at the plow would cease, and work would become casual Edenic berry picking, leaving endless time for artistic creation, amorous intrigues within the communes, and periodic love wars between the nations. No more war-wars, needless to say. But the youth would still need the pomp and glory of campaigns, so it seemed likely to Fourier that adolescents would now and again form up in vast armies of love, descending on Asia, say, in a conquering carnival of sexual acrobatics and great costumes. Imagine a cross between the Red Army and Cirque de Soleil.

One other thing. Hermaphrodites. Not timid ones, but big, mean ones. They wouldn’t last forever, but evolution might need to generate them for a time in order to transform the social order and enhance our sense of gender equity:

To put an end to the tyranny of men there would have to be a century of a third sex, both male and female, and stronger than the male. This new sex would prove by the rod that men, as much as women, are made for its pleasure.

For Fourier, whose writings are one continual euphoric spasm of optimism, the “plaint of nature” was soon to become the “plaint of misogynists.” They visit him suddenly from the future, their trousers torn, weeping: nature, sex, politics, and science. Squared.

I suspect Fourier is not getting much airtime at the Supreme Court these days, but it might make sense to send the justices a copy. So far he seems to be right about the global warming part anyway. Bacon’s mistreatment of nature would seem to be to blame for all that, but it’s nice to think that maybe, just maybe, the cause lies in an improvement in the global quotient of sexual satisfaction. Beats the hell out of blaming it—à la Alain de Lille—on homosexuals. Doubtless there is a Bible thumper out there right now, in some strip-mall house of worship, making that very claim.

It has never been easy to decipher what nature is trying to tell us, but we have never stopped listening, never stopped looking for signs, and never stopped figuring masks from which we can take dictation, or behind which we can hide as we lecture each other about our desires. Nature does indeed have a way of showing up unannounced. We do the talking.