The unknown is the largest need of the intellect.

—Emily Dickinson, 1876Queer Theorem

Dark rooms, deadly machines, and dangerous theories—toward a life beyond mechanistic science.

By Samantha Hunt

The Deer, by Gustave Courbet, c. 1865. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rubel Collection, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997.

Haul

It can take so many years to understand all the truths of a single moment. Our dates were older fisherman. If I hadn’t been young and dumb, I would’ve understood that our dates were also drug dealers. That the reason for this fancy meal far from our town was to celebrate getting away with it all, breaking the law in a big way. I was a gangster’s moll who didn’t know my date was a gangster, who didn’t even know he was my date. I thought he was a friend of my cousin’s. Courses and cocktails kept coming.

Dumb is not a fair adjective when I think of all the places dumb and discovery intersect: teenagers, new parents, failed experiments, luck. At fifteen I was so curious about the world, negotiations often felt like bargains made with death. A curiosity close to killing.

How many truths can exist in one small space? A kiss, a meal, an occupation, a body, a bomb, a desire, an essay, an experiment. Camera A. Camera B. Camera Z. Camera 533.

Flowers

Science is observational and evidentiary. Please accept this wild bouquet of evidence I have collected.

Wolves

At thirty-nine I became a mother in a huge way, three babies in two years, a multiple birth. It felt like a tidal wave surprised me, deposited these small humans in my lap. Having a baby is not unusual, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t the strangest thing ever. The shifts are tectonic and often obscured.

Explorer’s Map 2 (Topsy), by Gregory Block, 2016. Scorched aluminum cans, 48 x 63 inches. © Gregory Block, courtesy the artist.

If I wrote the full truth of what I was thinking the first years mothering three, a reader would wonder why no one dropped me off at a sanitarium, that place where they keep all the sanity. I don’t wonder anymore. I was not relieved of my mothering duties, because there was no one else to do them. My mom tried. My dad died young. My husband was also fighting to stay afloat. My siblings have their own lives and children. So another idea of truth was accepted: Samantha is fine. This kind of fine: I told my husband he was having an affair with my best friend. I told my mom I had cancer. I told my best friend wolves were circling my house and wanted to eat my babies. I told my sister there was a man living in my basement.

None of this was empirically true to anyone but me.

I told the lady who owns my local veggie restaurant that the twelve-year-old foster kid down the road from my house was evil. Instead of putting me to bed, saying, “Shush,” she told me, “You need to buy some mace. You need to buy a gun.”

What makes a new mother experience such an expanded reality?

Proximity to death, proximity to life. God, the abyss, the enormity of all wonder; science and nature is right there in front of our sleep-deprived eyes, but no one miraculously appears to explain the mystery of birth or even the mystery of hormones. In fact, all the world wants to know is: Boy or girl? Breast or bottle? When will you go back to work? Cloth or disposable? How did you lose all that weight?

Normalize what’s astonishing. Categorize and get back to work.

I’d growl, saliva and blood dripping from my jaws, my hair matted as any beast. I just made three deaths. I just made six eyeballs. I will never lose this weight.

Electrocuted

From the outside, it didn’t look like a great center of healing. Sleet was falling on top of old snow. Abandoned cars, trucks, tractors, busted refrigerators, and tools were strewn about the driveway and yard. A handful of metal utility sheds were stuffed with bits, bolts, and broken-down things.

The man who lived here had an interest in reproducing inventor Nikola Tesla’s work. Lately he’d been focusing on Tesla’s ideas about healing the body with electricity. I’d been invited to this house and laboratory because I’d written a book about Tesla. Though the place looked a bit like a junkyard, a friend with cancer had been receiving treatments here. He was also doing chemo. He was getting better. I was not sick, excepting the postpartum madness no one would acknowledge.

Two men met me in the driveway, or three men. I don’t remember how many men met me in the driveway. I don’t remember how I got inside. I worry these holes will make you doubt the truth of this story. These holes are the truth of this story.

Mortal Blush

What do you know? I mean, What do you know without your cyborg parts attached?

Brian Blanchfield wrote his 2016 book Proxies: Essays Near Knowing using no outside sources. He wrote what he knows in his body. The book contains essays on Owls, Peripersonal Space, Locus amoenus, Sardines, Confoundedness, Tumbleweeds, and Man Roulette. Proxies makes a person feel human again. It’s a corrective for a post-truth, technology-choked era because Proxies is really about what it means to have a body that is mortal, to live with our own damaged selves and the places where we fail. Blanchfield has included a twenty-page endnote amending, confessing, and celebrating the facts he got wrong. Here are the faults, the flesh, the holy wonder of our undigitized minds. Here’s the truth of our wrongness.

What do I know? I know my memory is flawed. I also know that one day when my children were babies, I drove to a mad scientist’s house where I exposed myself to 200,000–300,000 volts of electricity intentionally. I also know it didn’t kill me.

Calculation

When have you been closest to death? How many times have you almost died? Why?

Names Have Been Changed

I was invited into a large garage like the truck room of a fire station. Every bit of space, outside a number of cleared paths, was filled with bits of projects in media res. Spools and tools, rolls of wire, metal, saws, circuits, all the materials a modern inventor might require. There, dashing up and down the aisles, leading me from one project to the next like the most knowledgeable docent and overly excited child, was a man, healthy seventies, casually dressed, bald and shining, talking a blue streak as one who rarely receives visitors and must use this opportunity to fill me up with all the latest reports of his work.

I’ll call the man Les because I’m concerned about the legality of his experiments. Though I run the risk of sounding unreliable yet again, names have been changed.

Tesla

When I wrote my book about Tesla, I thought he belonged to me alone. I had never heard of him before. No one had ever taught me about him in school, and certainly no one had ever named a car after him. I knew only of Tesla the hair-metal band. When I discovered Tesla the poet-inventor, who built a motor powered by june bugs at age nine, and later harnessed Niagara Falls, and later concocted ways to photograph thought, it seemed I’d dreamed him into existence. Thus he belonged to me, only me.

Tesla worked independently in laboratories he built himself with little corporate or military interference. He invented radio. He invented our modern AC electrical system. But as he often failed to protect his patents—not believing a person could own thunder and lightning—eventually he could no longer afford a proper laboratory. He then made his inventions in his New York City hotel rooms, in his mind.

What’s the difference between invention and discovery? Is it just a question of ego? Or is it one of money?

Living with Tesla’s legacy and papers for more than three years of research, one hard thought kept cropping up. Everywhere I knew people who were making buildings, mugs, plays, paintings, sweaters, chocolate, operas, but I didn’t know any people, except children, who were trying to fly, who were grafting DNA for wings. I didn’t know anyone with a basement lab made for playing with protons. I wondered why we are well acquainted with the phrase starving artist while the term starving scientist does not even exist.

A Prince in a Dead Monarchy

Les began by telling me he is a prince in a dead monarchy. He produced an issue of Paris Match to prove it. He told me that when he was a child, he was visited by the ghost of a guru. He strolled me through his workshop, where I saw moments of small obsessions: a copper coil he’d been winding for months, freshly machined silver filings. Les was beaming, so I knew it had been a long time since someone had taken him seriously. Though his excitement was contagious, it did little to convince me of his stability.

How often was Tesla greeted by people who smiled at him as if he were a damaged child?

Then Les said, “It’s time to see the machine.”

Trailways

That same fifteen-year-old summer of my gangster date, I took an eleven-hour bus ride on a Greyhound. A woman seated in front of me turned back to confide, feeling she could trust me, that I might be able to help her. She said she had stumbled across a ring of Nazis. At first I thought she meant jewelry. She wondered if I might have some connections that could expose this hate group. As an early introduction to the paranoid mind, this woman carved out a new skepticism in me. She meant, Adults don’t all share one right, correct, proper reality. That was news. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe Nazis were active in America. I didn’t believe she was turning to me for help.

A few years later, in the early 1990s, renowned psychiatrist and Harvard professor John Mack published accounts of his patients’ alien-abduction narratives. The narratives shared common themes: sudden appearances, large eyes, beams of light, a spaceship, a physical examination, and, afterward, increased spirituality and environmental concern for our planet. When Mack was asked whether he believed his patients had been abducted by aliens, he told the BBC, “I would never say, Yes, there are aliens taking people. I would say there is a compelling, powerful phenomenon here that I can’t account for in any other way, that’s mysterious. Yet I can’t know what it is, but it seems to me that it invites a deeper, further inquiry.” While Mack wondered if these experiences were visionary or transcendental in nature, he also believed they were no less real in their immateriality. If the result was an increased love of humanity, love of our planet, does it matter if they are real or not?

The dean of the Harvard Medical School recruited a committee to investigate Mack’s clinical practice. The committee was chaired by Dr. Arnold Relman, editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, an esteemed, peer-reviewed publication dating back to 1812. The committee found Mack to be professionally irresponsible for giving “credence whatsoever to any personal report of a direct personal contact between a human being and an extraterrestrial.”

When the existence of the committee was made public, the academic community questioned the validity of the investigation. After plenty of public shaming, Mack’s academic freedom was eventually reaffirmed by Harvard. Though, of course, a cleared name never regains total clarity.

The Internet

I now receive email from men who also believe that Tesla belongs to them alone. Some of these men are angry that I, a woman, a nonengineer, speak for Tesla. Some of these men host ideas about life on Venus, the spirit molecule, free energy, government cover-ups and conspiracies. Some of these men are just glad Tesla has finally been recognized. I like the mad men the best. I imagine they have good dreams.

Morphic Resonance

In April 2008 British biologist Dr. Rupert Sheldrake was stabbed by a paranoid schizophrenic. The knife cut into his leg very close to the femoral artery. He had just finished delivering a talk about the “Extended Mind” at the International Science and Consciousness Conference in Santa Fe. This brush with death, with the body, makes a fine metaphor for the controversy and criticism that buffets Sheldrake’s career.

Sheldrake’s theory of morphic resonance explores the biological dimension of our connectedness. He studies telepathy. There’s a certain humility and democracy to his experiments. Why do people know when they are being stared at? Can you wake up a sleeping dog or cat by staring at it? Why do pets know when their masters are returning home? How do murmurations of starlings function? How do crystal formations know how to grow? How do we explain the sensation in phantom limbs? Why do you sometimes think of a friend right before she calls you? How do homing pigeons know their ways home?

Interviewed in the Guardian four years after the attack, Sheldrake described these phenomena as those “which people are generally fascinated by and made to feel stupid about.” Sheldrake studied biochemistry at Cambridge, where he won the university’s botany prize. He’s been a researcher at the Royal Society, a Harvard scholar, and a fellow of Clare College. Nothing to feel stupid about. Still, in battles waged on his Wikipedia page, he’s been called a parapsychologist and a pseudoscientist. Some critics have said his work lacks evidence, is inconsistent with established scientific theories, and contains magical thinking. He has even been called a “former biochemist,” as if a person could awaken one day having forgotten all he knows from the field of biochemistry.

Sheldrake survived the knife attack.

His most adamant critic was the late Sir John Maddox, a man who served for decades as editor of Nature magazine, yet another esteemed publication founded in the nineteenth century. In Nature, Maddox wrote a review of Sheldrake’s first book, A New Science of Life, published in 1981.

Even bad books should not be burned; works such as Mein Kampf have become historical documents for those concerned with the pathology of politics. But what is to be made of Dr. Rupert Sheldrake’s book A New Science of Life? This infuriating tract has been widely hailed by newspapers and popular science magazines as the “answer” to materialistic science, and it is now well on the way to becoming a point of reference for the motley crew of creationists, anti-reductionists, neo-Lamarckians, and the rest. The author, by training a biochemist and by demonstration a knowledgeable man, is, however, misguided. His book is the best candidate for burning there has been for many years.

On the BBC years later, Maddox again attacked. “Sheldrake is putting forward magic instead of science, and that can be condemned in exactly the language that the pope used to condemn Galileo, and for the same reason. It is heresy.”

Galileo is a curious choice if Maddox aimed to delegitimize Sheldrake because Galileo, the heliocentrist, was, of course, right. It’s hard not to read all this as schoolyard taunting, and surely the process of critique is beneficial for both sides to reconsider where they might be too attached to their preconceptions. But Maddox’s narrow-mindedness feels so inconsistent to his job as an editor and a scientist that I wonder if perhaps he intended this provocation to fire up controversy in order to bring attention to Sheldrake’s work, an act that the mantle of his prestigious post forbade. That is, ultimately, what his review did.

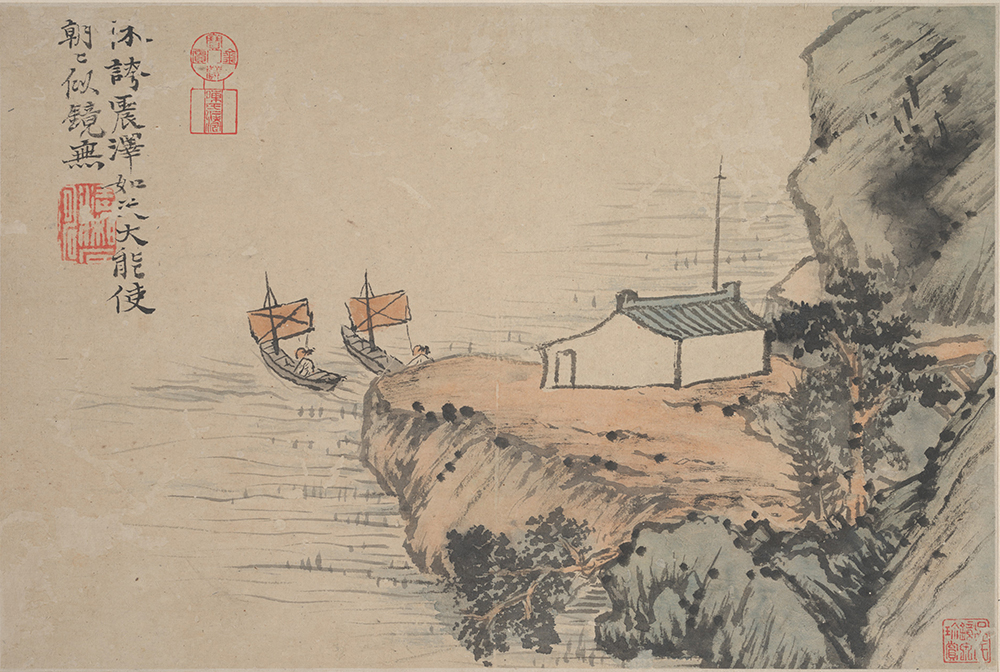

Leaf from the album Searching for Immortals, by Shitao, c. 1700. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of John M. Crawford Jr., 1988.

Richard Dawkins, the evolutionary biologist, atheist, and author, is another Sheldrake critic. The preface to his book The God Delusion quotes the philosopher Robert Pirsig: “When one person suffers from a delusion, it is called insanity. When many people suffer from a delusion, it is called Religion.”

As much as I enjoy considering the idea of group insanities, it seems that a better way to think about belief is to remember that it is a story, and stories imbue our every cell. Lives are controlled by fictions, such as memories, anticipated social narratives, paradigms, politics, and time. These are all fictions we think of as truths. And yet lives unfold because of the stories we decide to listen to, good or bad.

Baal

I’m compelled to make a strict distinction between multiple truths and fake news. Donald Trump insists there was massive voter fraud in the 2016 election. He tells the citizens of Philadelphia their crime rate is “terribly increasing,” or he spews his long-lived birther anthem, doubting Barack Obama’s homeland—a “truth” Trump finally retracted. He then insists his version of the story is the only version of the story and, like a child in a tantrum, refuses to listen to other voices or sources. He lies to comfort his fragile ego.

Compare this to Brian Blanchfield’s approach in Proxies. Blanchfield asks what one body, riddled with flaws and holes, knows, then confesses the errors in that knowing, encouraging more questions, more experiments, multiple takes and tries, new ways of reading the evidence. It is rigorous without being adamant. It is humble. It is tolerant of differences. It collects facts broadly.

Fake news is told by the insecure, who can admit no faults. Fake news, like a blind adherence to religion, insists, “This is the only truth! I am wearing blinders! And I am the only one who is right!” Fake news is scared. It practices an avowed insistence on a singular narrative, a singular egocentric, highly uninformed channel.

Edgar M. Welch, a young father and, so far, the most famous victim of fake news, luckily did not kill anyone when he showed up at Comet Ping Pong pizzeria heavily armed, ready to liberate the phantom children who were being held in the restaurant as sex slaves for Hillary Clinton. Mr. Welch told the New York Times after his arrest, “The intel on this wasn’t 100 percent.” Indeed. The intel on anything, everything, outside of death, will never be 100 percent. The only question is, Will we ever be brave enough to acknowledge that truth?

Magic

Science is also endangered by fakery and alternative facts. It is endangered when people say “magic” or “angels” or “intelligent design,” as these are code words for, Don’t ask further questions. Wonder can’t be explained. But still, things happen I cannot explain. The unexplainable needs to be where science begins. Maybe telepathy will one day seem as mechanistic as the moon. Maybe one day we will photograph thought or record the energy released by the dead, and even if we never do, I hope leagues of scientists spend their lives trying.

The problem I have with the supernatural is in the “super” part. Describing phenomena as supernatural robs the natural world of its due. I have visited Brookhaven National Laboratory and seen the work they are doing there. It is absolutely super. It is even beyond super, but it is never supernatural.

A promised idea of perfection in a removed heaven is hard to swallow when faced with the crystallization of snowflakes, the decomposition of dead leaves to humus, dead people to dirt, and the birth of our universe. What further heaven could people want than to become part of a tree? Distant heavens are a terrible threat granting permission to destroy the heaven we already have here.

Legos

What is to be gained in fundamentalist thinking, materialist science, and binary divides? What are the benefits in a slash-and-burn, mechanistic approach to science that says, If it doesn’t fit, if it is inconsistent with established scientific theories, get rid of it. Dawkins writes, “We are survival machines—robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes.” This idea of human machines has had devastating repercussions in the health-care industry.

Once I went to a specialist for headaches. He told me that he could help me with the pain in the back of my head, but when the pain was in the front of the head, I would have to visit another doctor, as if I were built of Legos. I conjured an image of Steve Martin’s medieval barber, Theodoric of York. “Why, just fifty years ago we would have thought your daughter’s illness was brought on by demonic possession or witchcraft, but nowadays we know that Isabel is suffering from an imbalance of bodily humors, perhaps caused by a toad or a small dwarf living in her stomach.”

I believe what I can feel, and I don’t feel like a machine. Sometimes I wish I were, but I’m not. I am affected by fictions in very real ways. The novels I inhaled as a girl, stress, the complex hero-making I work on my dad’s bones, and even here, the smallest example: last night I tossed and turned because my grandmother died recently and I miss her. I had been cleaning out her condo and had been stopped cold by the finality of her enormous stamp collection, a work she compiled from ages 5 to 101. I woke that night with such heaviness, worry, and dread of death. I blinked in the darkness. But in a matter of moments, I heard small footsteps coming down the hall to my room. One of my daughters climbed into bed beside me. There are multiple reasons why this might have happened, but I choose to believe my granny sent my daughter to comfort me. That reason feels best, most right. It is the finest story I can tell myself. I fell back asleep with her warm body beside mine.

Friday the Thirteenth

“Okay. Where is the machine?”

I followed Les outside.

What kept me moving forward in that moment? Was I operating under the influence of some entrenched horror-movie narrative? (See: fiction made real.) Had I become that girl on the screen who passes through one dark door and then the next, and everyone at the cinema is screaming, “No! No!” because the audience realizes the psycho killer is behind door number three waiting to chop our heroine to bits?

When they shout “Long live progress,” always ask, “Progress of what?”

—Stanisław Jerzy Lec, 1957In a small house at the back of Les’ property, there was yet another man, not an albino but nearly as pale, with long white-blond hair. He looked a bit like Edgar Winter. He smiled. Les smiled. I was led down into the basement, to a small room built within the larger room. There was a wooden bench and some wall pegs as one might find in a spa. “You can get undressed here.”

Both Les and the nonalbino headed back upstairs.

Witches

In Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers, Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English explore contemporary health care and the dangers in professionalizing the crafts of nursing and doctoring. They write, “We are mystified by science, taught to believe that it is hopelessly beyond our grasp. In our frustration, we are sometimes tempted to reject science, rather than to challenge the men who hoard it.”

The word hoard has never frightened me as much as it does here. First, it draws my attention to the fact that every scientist I’ve mentioned above is an older white man. Second, it causes me to imagine science as the property of a few, languishing in formaldehyde on a high shelf where only the stasis of preproven ideas is allowed. Dust settles. Science withers and superstition takes root among the uninvited, the non-peer-reviewed. When they are told their observations and evidence are not science, they will instead call these wonders magic.

An amateur painter produces a watercolor, and we name this person an artist. When I watch snow melt in the forest, am I not a scientist? And if not, why not? Is science afraid of the amateur, the nonprofessional?

My daughters’ backyard science experiments are strong, magnificent, and beautiful but often border on the poetic and imaginary. This morning one daughter asked, “What does the sun smell like?” To me, the nonprofessional scientist, this exploration of the sun’s odor seems vitally important. What will happen when access is denied to the nonprofessional, when dumb and discovery never have the chance to meet?

Lightning Orchestra

I undressed. Mildew, odd men, icy rain. I was about to electrocute myself for reasons I couldn’t totally understand yet. Still, I felt no more naked than I do already, which is to say, very naked, because with me in the basement, with me always, is the vulnerability my daughters brought. Their reckless little hands control my happiness and being. I am in love. I am at their mercy.

Yet here I was. I saw the door to the small room where the Tesla device of electronic healing was beginning to hum. I opened the door. If, as Dawkins says, my goal as a machine is to protect my genes, why was I there? Why can I not even remember who was taking care of my children that day?

I stepped inside the room. I didn’t want the vulnerability of mothering ever to equal fear. I wanted it to become openness. My children had blown my life open. What if I didn’t collect the parts but just remained open, broken, scattered, commodious? I closed the door behind me. A machine would go home and protect her gene pool, her progeny. A machine intent on survival wouldn’t walk into the unknown. Clearly, we are so much more than selfish gene machines.

Design for a Clock in the Form of an Elephant with an Indian Driver, from a 1315 edition of The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, by al-Jazari. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1955.

The room was totally dark. Real darkness erases the border of a body swiftly. I was uncertain where I began or ended until a rich light dawned. In front of me, behind a small safety railing, was a glowing violet mushroom. As I bathed in it, the light grew stronger. Eventually I walked closer to the light and the noise it made. I went hands first as one might approach an edge. As I advanced, blue lightning bolts shot from my fingertips; with them I could conduct a lightning orchestra. I’ll never forget that.

The room became thickly charged. Closer still, tiny baby-blue bolts shot not just from my fingers but from multiple neural pathways, like a map of acupuncture points. I was illustrated as energy, a simple body and so totally complex that after forty years living in it, I still didn’t know how it worked.

My hair, long and heavy, blew behind me. A strong wind was somehow gathering in that closed space. I don’t pretend to understand the engineering of the device or how that much power, 200,000–300,000 volts, was produced in a depressed basement. I don’t know why it didn’t kill me. Maybe it had to do with high voltage/low current, or with being insulated, or with the skin effect. I don’t know. I do know that I felt lucky to be there, an explorer seeing something very few people will ever get to see.

After fifteen or twenty minutes, I left the room and got dressed again.

A Monarchy of a Dead Prince

Did 200,000 volts of electricity change me?

If my body were made of rigidly packed sand, Les’ machine inverted me, held me up by my ankles. Each grain seemed subtly shifted, shaken, awakened. But subtlety is a problem when it comes to Western medicine. We wonder, Did it work? Did I get my money’s worth? We want our results to be dramatic, devastating even.

From a report in the New York Times: “Prescription fentanyl is used to treat cancer pain and as an anesthetic for surgery. Even small amounts of it can be deadly. The drug is so powerful that law enforcement officers have to wear gloves when searching for it, as just a tiny bit can get into the skin and, depending on the amount, can be fatal.” That ancient physician’s credo, Do no harm, is a joke under capitalism.

I left Les’ house. It was still an awful day, freezing purple rain.

Queer Science

One inquiry I get from Tesla fans is, “If Tesla were alive today, would he be medicated?” And the rejoinder, sometimes unspoken, is, “If he’d been medicated, would he have invented all he invented?”

Tesla manifested a handful of conditions we might now call mental illness. Despite housing a large population of New York City’s pigeons in his hotel rooms, he had a terrible germ phobia. He feared pearl earrings and human hair. He was also obsessively, compulsively controlled by the number three, living in rooms divisible by the magic number—3327 at the Hotel New Yorker. The question of a medicated Tesla suggests a swiftly narrowing, choking idea of what it means to be normal, that noxious, cruel word.

Science and health care need some breathing room. Queer theory—that field of critical inquiry commonly applied to politics, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, and the arts—could offer it. There is no black and white. No binary positions. No on or off, sick or cured, normal or deviant, failure or success. It is a theory that defies singular definition with an abundance of identities.

Computers are binary. Machines are binary. Humans are not.

What would be lost if we accepted a spectrum of science where the mechanistic and the materialistic existed at one end and utter mystery at the other? Queer physics, queer healing, queer chemistry, and all of it conducted by starving scientists and mad artists.

Random-Access Memory

Tesla failed a lot, probably more than he succeeded. He forecasted Samuel Beckett’s “Fail again. Fail better.” So the only problem was that after Tesla claimed to have spoken with Martians, much of his financing dried up. What might he have discovered had he had access to greater resources, if funding ever flowed to the extremes? For Tesla, it was never a problem of lacking imagination but rather convincing others that all the unseens—dreams, fantasies, fictions—made material effects in the material world. His best inventions, including the AC motor that continues to drive our modern electrical system, came to Tesla in a flash, as an immaterial vision painted on the air.

Fail Best

I had a digital recorder running on the day I spent with Les. At home I transferred the data to my computer, and a month later I spilled a cup of coffee on that computer. One truth forever erased. One more beautiful failure on my way to finding my truth. I was left to rely on my own original random-access memory.

So. That’s what I did, that is what I do. I asked the foster kid down the street, What do you know? I asked the paranoid woman on the Greyhound bus. I asked the mad scientist and the thirty-nine-year-old mother of three. I asked the mother of the mad scientist, What do you know? And Steve Martin. And you, I would ask you, What do you know?

And Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English and all their fellow scientists. What do you know? What do you know? What do you know? I asked the crazy people on the internet. They know a lot. A different lot, but a lot. I asked my daughters. I asked the aliens. I asked the vegetarian and Maddox and Dawkins and Galileo and Sheldrake. I asked the almost-albino and the man I imagined in my basement, and I asked the fifteen-year-old girl I once was, What do you know?

She said, “I know a lot more than I did before.” Then she told me a story about the night she went on a date with a fisherman who turned out to be a drug dealer who turned out to be a fifteen-year-old boy who turned out to be a memory and a time traveler and a chemist and a biologist and the child of some mother who one day asked herself, What do I know? What do I know?