A Jewish man with parents alive is a fifteen-year-old boy, and will remain a fifteen-year-old boy till they die!

—Philip Roth, 1969Brotherly Love

Norman Maclean fights his brother.

When you are in your teens—maybe throughout your life—being three years older than your brother often makes you feel he is a boy. However, I knew already that Paul was going to be a master with a rod. He had those extra things besides fine training—genius, luck, and plenty of self-confidence. Even at this age he liked to bet on himself against anybody who would fish with him, including me, his older brother. It was sometimes funny and sometimes not so funny to see a boy always wanting to bet on himself and almost sure to win. Although I was three years older, I did not yet feel old enough to bet. Betting, I assumed, was for men who wore straw hats on the backs of their heads. So I was confused and embarrassed the first couple of times he asked me if I didn’t want “a small bet on the side just to make things interesting.” The third time he asked me must have made me angry, because he never again spoke to me about money, not even about borrowing a few dollars when he was having real money problems.

We had to be very careful in dealing with each other. I often thought of him as a boy, but I never could treat him that way. He was never “my kid brother.” He was a master of an art. He did not want any big-brother advice or money or help, and, in the end, I could not help him.

Since one of the earliest things brothers try to find out is how they differ from each other, one of the things I remember longest about Paul is this business about his liking to bet. He would go to county fairs to pretend that he was betting on the horses, like the men, except that no betting booths would take his bets because they were too small and he was too young. When his bets were refused, he would say, as he said of Izaak Walton and any other he took as a rival, “I’d like to get that bastard on the Blackfoot for a day, with a bet on the side.”

By the time he was in his early twenties he was in the big-stud poker games.

Circumstances, too, helped to widen our differences. The draft of World War I immediately left the woods short of men, so at fifteen I started working for the United States Forest Service, and for many summers afterward I worked in the woods, either with the Forest Service or in logging camps. I liked the woods and I liked work, but for a good many summers I didn’t do much fishing. Paul was too young to swing an axe or pull a saw all day, and besides, he had decided this early he had two major purposes in life: to fish and not to work, at least not allow work to interfere with fishing. In his teens, then, he got a summer job as a lifeguard at the municipal swimming pool, so in the early evenings he could go fishing and during the days he could look over girls in bathing suits and date them up for the late evenings.

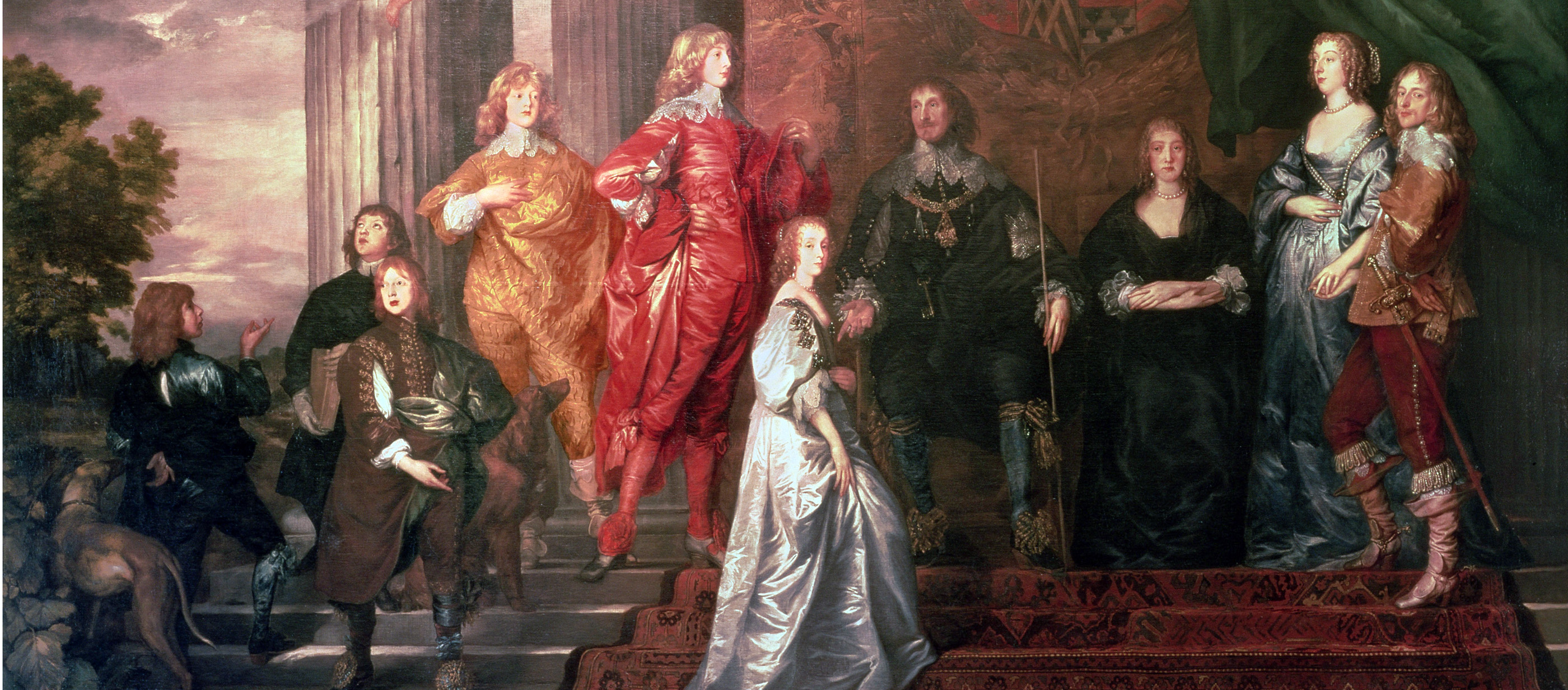

Philip Herbert, Fourth Earl of Pembroke, and His Family, by Sir Anthony van Dyck, c. 1635. The Earl of Pembroke’s Collection.

When it came to choosing a profession, he became a reporter. On a Montana paper. Early, then, he had come close to realizing life’s purposes, which did not conflict in his mind from those given in answer to the first question in The Westminster Catechism.

Undoubtedly, our differences would not have seemed so great if we had not been such a close family. Painted on one side of our Sunday school wall were the words, god is love. We always assumed that these three words were spoken directly to the four of us in our family and had no reference to the world outside, which my brother and I soon discovered was full of bastards, the number increasing rapidly the farther one gets from Missoula, Montana.

We also held in common the knowledge that we were tough. This knowledge increased with age, at least until we were well into our twenties and probably longer, possibly much longer. But our differences showed even in our toughness. I was tough by being the product of tough establishments—the United States Forest Service and logging camps. Paul was tough by thinking he was tougher than any establishment. My mother and I watched horrified morning after morning while the Scottish minister tried to make his small child eat oatmeal. My father was also horrified—at first because a child of his own bowels would not eat God’s oats, and, as the days went by, because his wee child proved tougher than he was. As the minister raged, the child bowed his head over the food and folded his hands as if his father were saying grace. The child gave only one sign of his own great anger. His lips became swollen. The hotter my father got, the colder the porridge, until finally my father burned out.

Each of us, then, not only thought he was tough, he knew the other one had the same opinion of himself. Paul knew that I had already been foreman of forest-fire crews and that if he worked for me and drank on the job, as he did when he was reporting, I would tell him to go to camp, get his time slip, and keep on down the trail. I knew that there was about as much chance of his fighting fire as of his eating oatmeal.

We held in common one major theory about street fighting—if it looks like a fight is coming, get in the first punch. We both thought that most bastards aren’t so tough as they talk—even bastards who look as well as talk tough. If suddenly they feel a few teeth loose, they will rub their mouths, look at the blood on their hands, and offer to buy a drink for the house. “But even if they still feel like fighting,” as my brother said, “you are one big punch ahead when the fight starts.”

There is just one trouble with this theory—it is only statistically true. Every once in a while you run into some guy who likes to fight as much as you do and is better at it. If you start off by loosening a few of his teeth, he may try to kill you.

I suppose it was inevitable that my brother and I would get into one big fight which also would be the last one. When it came, given our theories about street fighting, it was like the Battle Hymn, terrible and swift. There are parts of it I did not see. I did not see our mother walk between us to try to stop us. She was short and wore glasses and, even with them on, did not have good vision. She had never seen a fight before or had any notion of how bad you can get hurt by becoming mixed up in one. Evidently, she just walked between her sons. The first I saw of her was the gray top of her head, the hair tied in a big knot with a big comb in it, but what was most noticeable was that her head was so close to Paul I couldn’t get a good punch at him. Then I didn’t see her anymore.

The fight seemed suddenly to stop itself. She was lying on the floor between us. Then we both began to cry and fight in a rage, each one shouting, “You son of a bitch, you knocked my mother down.”

She got off the floor, and, blind without her glasses, staggered in circles between us, saying without recognizing which one she was addressing, “No, it wasn’t you. I just slipped and fell.”

So this was the only time we ever fought.

Perhaps we always wondered which of us was tougher, but if boyhood questions aren’t answered before a certain point in time, they can’t ever be raised again.

© 1976 by The University of Chicago Press. Used with permission of The University of Chicago Press.

Norman Maclean

From A River Runs Through It. Maclean’s father taught his two sons to fish and to believe in God, a pedagogy summarized at the opening of this novella: “In our family, there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing.” The University of Chicago Press in 1976 released the book, the first work of fiction the house ever published. When Maclean died at the age of eighty-seven in 1990, he left unfinished a study of Gen. George Custer and of the Mann Gulch Fire of 1949, the latter published posthumously as Young Men and Fire.