Fear is the foundation of most governments.

—John Adams, 1776Every Pebble Can Blow Us Sky-High

A reconsideration of The Wages of Fear, directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot.

By J. Hoberman

Yves Montand and Charles Vanel in a scene from The Wages of Fear. © Album / Art Resource, NY.

The Wages of Fear, directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot and first shown at the Cannes Film Festival in the spring of 1953, is movie as doom show: the four principal characters have signed on to a suicide mission, driving two truckloads of nitroglycerin across three hundred miles of winding, mountainous, badly paved roads. After a lengthy setup, the movie itself becomes a fuse of indeterminate length. “You sit there waiting for the theater to explode,” the New York Times critic Bosley Crowther ended his review when The Wages of Fear opened in early 1955 at the posh Paris Theater in Manhattan.

An evocation of human existence under threat of instant annihilation, The Wages of Fear is no less a manifestation of nuclear anxiety than the Japanese monster movie Godzilla (1954) or even Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964). In its way, The Wages of Fear—in production when the United States tested the first hydrogen bomb at Enewetak in the Marshall Islands—is cinema’s original articulation of that angst. Given its flirtation with total obliteration, the movie could have been titled, after Sartre’s 1943 magnum opus, Being and Nothingness.

On August 8, 1945, two days into the Atomic Age, Sartre’s then friend Albert Camus editorialized in the Resistance newspaper Combat that “the civilization of the machine has just achieved its ultimate degree of savagery... We find ourselves confronted with a new source of anguish, which has every likelihood of proving fatal.” at anguish undoubtedly factored in the pessimistic mood Life magazine reported shortly after among French intellectuals, including a grim apostle of Dolorism prone to glowering at pretty Parisians and sneering, “In twenty years you’ll be garbage in a coffin,” and members of the “cult known as existentialism.” Some eighteen years later, Life revisited the scene and determined the cult had become “the mainstream of artistic creation...Like it or not, we are all consumers of existentialism.” In unleashing a movie that can be considered, along with Sartre’s No Exit and Camus’ The Plague, as an existentialist allegory, the man who made The Wages of Fear proved himself both a consumer and a creator.

At the height of his career, Clouzot personified a commercial cinema of quality, having produced and directed France’s two great post–World War II, pre–Nouvelle Vague international hits, The Wages of Fear and the marital thriller Diabolique (1955), as well as the classic middlebrow art doc Le mystère Picasso (1956). Born in 1907 to a bookseller in Niort, France, Clouzot was a prodigy who gave piano recitals at age four and wrote plays as a child. He studied law and political science in Paris, broke into films as a scriptwriter, and spent several years in Germany (before and after the Nazis seized power) as a director of dubbing at the UFA studio. Then, bedridden in a series of tuberculosis sanitariums, Clouzot furthered a twentieth-century education: “While resident there, I saw how human beings worked.” He also presumably saw how human beings died.

Clouzot was discharged before World War II broke out, but poor health kept him out of the French army. His directorial career began under the German occupation and was marked by scandal. Made in 1942, his first feature, L’Assassin habite au 21 (The Murderer Lives at Number 21), was a dark comedy that presented what might have been cinema’s first subjectively presented murder—an implication of the spectator that suggests an often-noted affinity with Alfred Hitchcock. Clouzot’s second film, Le Corbeau (The Raven), released in 1943, showed a provincial village terrorized by a writer of poison-pen letters that drove some people to suicide and others to crime.

As brilliantly nasty as anything Clouzot ever did, Le Corbeau was remade in Hollywood by Otto Preminger under the title The 13th Letter (1951) and made a profound impression on the young François Truffaut, who later wrote that it “seemed to me to be a fairly accurate picture of what I had seen around me during the war and the postwar period—collaboration, denunciation, the black market, hustling.” But although the movie can be read as a portrait—if not a critique—of the Nazi occupation, it was financed by a German company and approved by the German authorities; moreover, it was shown in Belgium and Switzerland under the provocatively generalizing title Province française.

Le Corbeau was directed from a script that had been written and registered in 1937, well before the occupation. Still, after liberation, Clouzot was accused of collaborating and was expelled from the French film industry—a lifetime ban that wound up lasting only two years. In 1947 he made the showbiz noir Quai des Orfèvres (released in the U.S. as Jenny Lamour) and was fully rehabilitated when the movie received the director’s prize at the Venice Film Festival; he was all but canonized when its follow-up, Manon, won the festival’s Golden Lion two years later. After making two less consequential films, Clouzot secured the rights to Georges Arnaud’s 1950 best seller Le salaire de la peur (The Wages of Fear). Hitchcock was also interested in Arnaud’s novel, but evidently the patriotic author would sell rights only to a French filmmaker.

It was a novel with a whiff of sulfur. Arnaud was a pseudonym for Henri Girard, who had been charged during the occupation with three grisly murders, including those of his father and aunt. Eventually acquitted, he relocated to Venezuela, where he was variously a prospector, a smuggler, a bartender, and a truck driver.

A French-Italian coproduction with multilingual dialogue and international casting, The Wages of Fear was part of a postwar attempt to create a European cinema positioned against Hollywood. It succeeded. The movie was Clouzot’s greatest triumph, a huge hit in Europe—the only movie ever to win the top prize at both the Cannes and Berlin film festivals—and especially successful in France, where it sold half again as many tickets as the Hollywood super-production Quo Vadis (1951).

Immediate theater of cruelty, The Wages of Fear begins with a fatalistic flourish of flamenco guitar chords and a close-up of four tethered cockroaches—the insects of the apocalypse and the playthings of a half-naked child, frisking in the dusty plaza of some wretched South American hellhole (actually reconstructed in the South of France). “Shakespeare, when his blackest bile was running, could hardly match this image as a metaphor for existence,” Time magazine would primly note in a remarkably hostile review. Sam Peckinpah must have agreed, having appropriated it for the opening shot of his nihilist Western The Wild Bunch (1969).

Located in an unidentified country that strongly suggests Venezuela, the godforsaken pueblo of Las Piedras (The Stones) is an ugly, buzzard-ridden dump populated by beggars, urchins, cynical soldiers of fortune, native layabouts, and random washashores who amuse themselves by idly stoning dogs or holding spitting contests in a sleazy cantina. Las Piedras is less a town than a composition in mud, misery, and torpor. There is no shade from the sun, yet the place is overshadowed by oil derricks built by the American petroleum conglomerate with the acronym SOC (as in Esso sí?).

People must have committed some terrible sins to be consigned to this hell, which has suffered massive unemployment since SOC took charge of the port. But if the largely unseen Americans control Las Piedras, the reigning prince is the tremendously unsympathetic Mario, a natty loafer played by pop idol Yves Montand. With his carefully knotted bandanna and jaunty cigarette wedged in the corner of his mouth, he suggests the ultimate left-bank apache. The beautiful, abject barmaid Linda (Clouzot’s wife, Brazilian actress Véra Clouzot, née Gibson-Amado) confirms Mario’s alpha status by entering on her knees, scrubbing the cantina floor in a tank top cut nearly as low as his, then happily crawling over to nuzzle his hand.

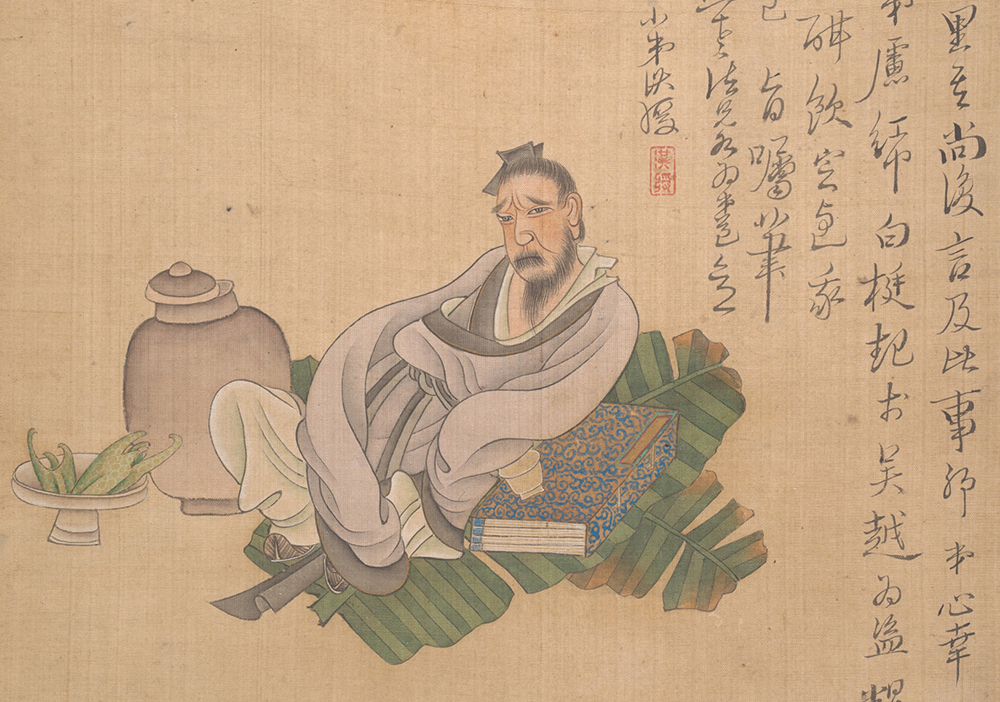

Self-portrait of Chen Hongshou as a dejected scholar (detail), 1627. Four years earlier, Chen’s first wife died and he failed the provincial examinations. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Wan-go H.C. Weng, 1999.

Although nobody appears to have signed up, Las Piedras might be the last derelict outpost of the French Foreign Legion. The movie is aggressively pan-European and openly racist both in its characters’ attitudes and its own use of National Geographic–style cheesecake in presenting the native extras. The dialogue is variously French, Spanish, Italian, and English, with the first serving as the language of love. A grizzled French gangster named Jo (veteran silent-film star Charles Vanel) lands in town, cruising Mario while both whistle the old, inordinately sexist Maurice Chevalier song “Valentine.” Mario immediately dumps Linda and jilts his roommate Luigi (the prolific Italian actor Folco Lulli), a bighearted paisan with a fatal lung infection, to hang out with the aging tough guy, showing him his pinups and sacred talisman, a metro ticket purchased at Place Pigalle.

The term Third World had just been coined in Paris by the economist Alfred Sauvy. The late 1940s through the early 1960s were a period of futile neocolonial wars—the Dutch in Indonesia, the British in Kenya, the French in Indochina and then Algeria—and American ascendance. “Where there’s oil, there’s Americans,” Mario notes. So it is in Las Piedras. Then a fire in a distant oil well, which can apparently be contained only by exploding the whole territory, creates a golden opportunity for the underemployed cream of the international scum brigade. Mario, Jo, Bimba (a German survivor of a Nazi slave-labor camp, played by Peter van Eyck), and Luigi are hired to drive the nitroglycerin over the mountains by the callous American boss O’Brien (William Tubbs, who had played a burly American priest in Roberto Rossellini’s 1946 film Paisan), two thousand dollars each if they can make it.

The payoff amounts to a ticket out of Las Piedras; the suicidal drive is the ultimate test of machismo. Yet the world clearly belongs to SOC. Before the movie ends, Clouzot even finds a way to literally rub his antiheroes’ faces in the reality of petro-imperialism in a sequence involving real oil that Life called “just about the most gruesome scene ever seen on film” and now seems a precursor of Werner Herzog’s recontextualized Gulf War eco-disaster documentary, Lessons of Darkness (1992), which also featured a lake of oil and flaming oil wells fought with fire.

Reporting from Cannes, Variety had speculated that Montand’s and Clouzot’s “commie leanings” might present a problem in the American market. (Actually, Montand, a committed leftist, was very suspicious of Clouzot, whom he considered a right-winger.) Indeed, Time read The Wages of Fear as a political allegory in which representatives of three NATO countries are “sent on a fool’s errand to pull U.S. chestnuts out of the fire.” Clouzot’s “idea is simple: hate America,” the newsweekly declared; his movie is “vicious and irresponsible” propaganda and “a picture that is surely one of the most evil ever made.” Why not call it godless too?

An hour into The Wages of Fear, the two trucks set off into a realm where, as one driver puts it, “every pebble can blow us sky-high.” Reveling in the pure dread of its basic situation, set in an indifferent universe, and featuring characters who can be vaporized at any moment, The Wages of Fear amply illustrates what has been called the five A’s of existentialism: alienation, absurdity, angst, anomie, and anxiety, even as it dramatizes every major existential trope—the condition of homelessness, the countdown to oblivion, the bridge over the abyss, the myth of Sisyphus (actually visualized twice, once when a giant boulder blocks the road and again when, having laboriously driven through a lake of oil, a truck slips helplessly back). Mario compares Las Piedras to a prison: it is easy to get to the town, but there is “no way out.”

The trucks speed through a nocturnal void or else a landscape marked with crosses, their drivers smoking like ends or bouncing apple cores off the skull and crossbones of a warning danger sign. The dialogue is relentless. “He’s just a walking corpse,” Mario complains of his partner, Jo. “And so are we,” the other drivers reply when all meet up along the boulder-blocked road. “I don’t feel like croakiing,” somebody says, provoking the reasonable answer, “Nobody does, but they croak anyway.”

When The Wages of Fear did finally have its American premiere, two years after its Cannes triumph, it was trimmed by forty-three minutes. Las Piedras appeared less squalid, all references to trade unions were omitted, O’Brien was less perfidious, and Jo’s sneering crack “Coca-Cola dans ton” (up yours) was suppressed, as were the suicide of an unemployed Italian worker—a scene in which Bimba expresses his dislike for women and refers to his role in the Spanish Civil War—and a conversation with a dying man pondering the “nothingness” hidden behind a Paris fence.

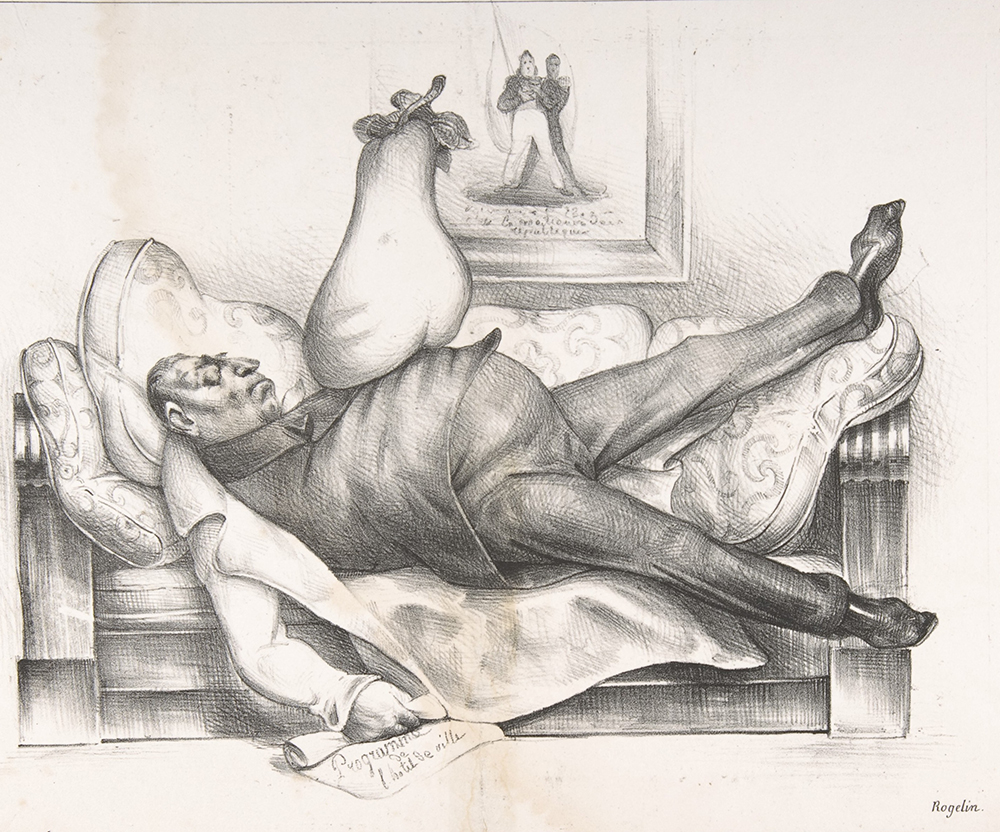

The Nightmare, by Honoré Daumier, 1832. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Edwin De T. Bechtel, 1957.

An early issue of Film Culture magazine published a detailed account of the excisions and suggested “a short film composed exclusively of the cuts” would provide “an animated fresco of the many prejudices and taboos that still haunt our cinema.” Some months after the movie’s U.S. release, the French distributor did show the press this fresco, described by the journalist Keith Irvine in The Nation.

Strange images appear, jumbled together. Curses are hurled as a jeep rushes down a tropical street, veering around a corner in a shower of mud. The dangling legs of a hanging man are seen. A naked little boy, with finger in mouth, stares innocently. There has been an accident of some kind. People run. A mestizo woman harangues an angry crowd. Somebody has been killed. An old man is struck on the mouth with a rock. ere is talk of trade unions, homosexuality, oil fires, life and death. What are we viewing? A surrealist film? Shots taken with a concealed camera? Reflections of the ferment in South America? No, this is a special presentation of scenes cut from the film Wages of Fear before it was distributed in the United States.

More than one contemporary critic found The Wages of Fear overblown and hackneyed. Manny Farber, who grouped Clouzot with such “water buffaloes of film art” as George Stevens, Billy Wilder, and Vittorio De Sica, considered the movie to be an inflated Warners action-drama, “a wholesale steal of the mean physicality and acrid highway inventions” of Raoul Walsh’s less prestigious 1940 truck drama They Drive by Night.

Still, enough remained to stun local critics. Even cut, depoliticized, and philosophically neutered, The Wages of Fear hit a raw nerve. The New York Herald Tribune called the movie a “pitiless thriller” with a “sadistic streak”; the Christian Science Monitor found it “unusually deplorable...cynically and heartlessly brutal.” Robert Hatch’s Nation review was painfully ambivalent: “I have rarely been so gripped by a picture, and never so disgusted with myself afterward,” he wrote. “In any moral sense, The Wages of Fear is a bad picture, cruel and essentially meaningless.”

Clouzot brazenly asserts the absurdity of the human condition. “Unlike Eurydice, the absurd dies only when we turn away from it,” Camus wrote in The Myth of Sisyphus. But The Wages of Fear refuses to allow us to avert our gaze. The courageous no less than the cowardly are condemned to an ignoble death. The movie includes a shockingly abrupt vision of a distant mushroom cloud. The offensive wise-guy ending asserts that life is meaningless and action is futile. The ultimate bang, a close-up of a corpse clutching a never-to-be-used metro ticket, is also a whimper.

Decades later, Hollywood director William Friedkin remade The Wages of Fear and capsized his career. Although hardly the disaster it was deemed when it opened in June 1977, only weeks after Star Wars reoriented the entertainment industry, Friedkin’s Sorcerer (named for one of the trucks) has characters even sleazier, driving vehicles more dangerously decrepit, for an oil company even more rapacious than in The Wages of Fear. Third World specificity is here archetypal. The natives are no longer displaced workers but restive primitives; nature is not indifferent but malevolent, the trees and vines seeming to reach out of the rainforest to snare the trucks.

Who lives in fear will never be a free man.

—Horace, 19 BCAs an exercise in jungle hubris, Sorcerer has affinities to Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (in production when Sorcerer premiered but not released until 1979). The sequence in which the trucks lurch mid-monsoon across a swaying bridge may be the most elaborately orchestrated of Friedkin’s career. His explosions are more elaborate and his ending is more fatalistic than Clouzot’s, but if The Wages of Fear dared to dramatize the human condition, Sorcerer was a lesser sort of existential adventure, a movie about showmanship and the hubris of its own making.

Clouzot had a larger point to make: fear feeds on fear. “It’s catching like smallpox,” one principal explains. “And once you get it, it’s for life.” Clouzot’s film is consecrated to the wages Camus earned from his experience of World War II and his dread of what might follow. In the 1946 article “The Century of Fear,” published in Combat, Camus wrote that fear “signifies and rejects the same fact: a world in which murder is legitimate and human life is considered futile.” So it is in our home, or rather, prison, Las Piedras.