“Abroad,” that large home of ruined reputations.

—George Eliot, 1866Enemy Aliens

The life of Austrian painter Paul Cohen-Portheim and the forgotten history of World War I internment camps.

By Andrea Pitzer

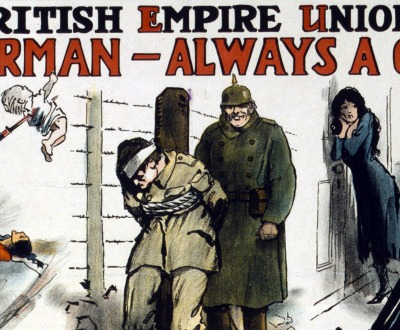

“Once a German—Always a German,” British Empire Union post–World War I poster, c. 1914–18.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

When Archduke Franz Ferdinand was shot point-blank in the neck on June 28, 1914, news of his assassination ricocheted from Sarajevo all the way across Europe before nightfall. In the ballroom of a Parisian amusement park that evening, Austrian painter Paul Cohen-Portheim asked a Viennese count what he thought was going to happen next. “Why should anything happen?” replied the count, surprised. Cohen-Portheim was comforted—there was no need to cancel his annual trip to England to paint the cliffs of Devonshire.

On June 28, it was possible to believe that the archduke’s death would have few repercussions, but by the end of July that illusion had collapsed. After several pleasant weeks in the English countryside, Cohen-Portheim traveled to London to discover that Serbia and his native Austria were at war. He considered withdrawing funds he had deposited at the local branch of his German bank, but the tellers assured him that a broader conflict was not expected. After a few days with friends in Richmond, an elegant suburb southwest of London, Cohen-Portheim returned to find that his money had effectively vanished.

Desperate for passage home when Germany declared war on Russia on August 1, Cohen-Portheim joined a crowd trying to enter the German consulate on Bedford Square. A diplomat stepped out from the doorway to say that two ships had been chartered but would carry only military reservists—everyone else was out of luck. Cohen-Portheim was stranded in suburban London with only ten pounds on which to live. He would have to survive on the kindness of his British friends.

On August 4, Britain declared war on Germany, and the next day Parliament passed the Aliens Restriction Act, transforming every foreigner born in Germany or Austria-Hungary into an “enemy alien.” Cohen-Portheim was required to register immediately at his local police station.

Octopus 1 (Codger), by Judy Fox, 2009–11. Terra cotta and casein paint, courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York.

As required by the new law, Cohen-Portheim visited a station near Richmond, only to be sent to another station, where officials should have given him a registration card listing the details of his newly restricted life: an enemy alien was not permitted to send letters to his family; he could not travel without permission more than five miles from the station at which he had registered; he could not own a camera, a car, an airplane, a motorcycle, or a carrier pigeon; he was forbidden military maps, clandestine signaling devices, guns, and ammunition. Cohen-Portheim, however, did not receive the new regulations, which he only learned after unintentionally violating any number of them.

For years, British newspapers had sounded the alarm about nefarious Germans, and in the eyes of many, registration of enemy aliens did not settle the issue. “Does signing his name take the malice out of a man?” cried the Daily Mail. As early as 1909, papers had reported (entirely imaginary) Zeppelin sightings on the British coast and warned of the threat posed by an expanding German navy. Newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe, owner of both the Daily Mail and the Times, further stoked the fear of invasion, warning that German waiters and barbers lurked at the heart of a hidden spy network.

During the first month of the war, reports of German atrocities in Belgium and France exploded into headlines—prisoners of war lined up before firing squads, children bayoneted, widespread civilian executions at Liège. But while some members of Parliament expressed outrage that not enough aliens had been rounded up at home, government ministers encouraged restraint. “To arrest all aliens wholesale, irrespective of their guilt or innocence,” declared Lord Chancellor Viscount Haldane, “was a policy as inhuman as it was inefficacious.”

But on May 7, 1915, a German submarine torpedoed the British ocean liner Lusitania, killing more than a thousand civilians. Anti-German riots erupted across the British Empire, from Johannesburg to Melbourne, striking at least three dozen neighborhoods in London alone. Looters ransacked German pubs and bakeries, stomping freshly baked bread and causing shortages the next day; children carted away stolen goods in wheelbarrows; windows were broken, dishes handed over to onlookers, pianos and harmoniums burned. In Liverpool, police took German enemy aliens into protective custody. The riots gave the government the chance to declare that mass internment was in the interest of enemy aliens themselves.

Less than a week after the Lusitania’s destruction, the government announced that all male enemy aliens of military age would be rounded up and sent to a camp on the Isle of Man. On the evening of May 24, 1915, a detective visited Cohen-Portheim and told the painter to turn himself in at the Richmond police station at ten a.m. the next day, saying, “Pack as if you were going for a holiday.” Cohen-Portheim filled two trunks in the hopes he would be gone a few days at most. In the morning, his last real friend in London accompanied him as far as the courtyard of the police station. From there he went by taxi to a camp in London’s East End, where a thousand German and Austrian men of fighting age squatted together in an open hall under a bombed-out glass roof. Given a metal disc with his prisoner number, Cohen-Portheim was relieved to learn he would only have to survive one night there.

At six a.m., armed guards marched the new prisoners through the streets of London to the train station. Crowds lined their path, spitting, throwing things, and shouting about Huns and baby killers. Cohen-Portheim was well aware of his pariah status. “Everybody felt something extraordinary was expected from him,” he wrote in Time Stood Still, his memoir of the almost three years he would spend as a prisoner in British internment camps. “But no one—except [British] soldiers—quite knew what to do in order to show his devoted patriotism.” At the train station, the prisoners’ nightmare suddenly reversed. They boarded a comfortable train to the coast, with a good meal and friendly civilian waiters. On arrival, soldiers took over again, ordering them onto a steamer, where they were locked standing-room-only into the hold while they sailed across the Irish Sea to Knockaloe Camp on the Isle of Man, which would eventually hold more than 23,000 enemy aliens.

Approaching Knockaloe in darkness, Cohen-Portheim saw a bright chain of arc lights on a hill, illuminating barbed-wire fences that stretched as high as eighteen feet. Thousands of inmates crowded inside the wire, initiating new arrivals by imitating their British tormenters: Huns! Baby killers! Cohen-Portheim’s feet sank into muddy clay. He surrendered his prisoner number and began to wait for the end of the war.

Jurist William Blackstone first defined the term alien enemy in his celebrated Commentaries on the Law of England in 1766. Summing up centuries of British common law, he wrote, “When I mention these rights of an alien, I must be understood of alien friends only, or such whose countries are in peace with ours; for alien enemies have no rights, no privileges…during the time of war.” The United States in 1798, anticipating war with France, created the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts, including its own Alien Enemies Act, which authorized the apprehension, arrest, or removal of males over the age of fourteen native to a country at war with the United States. (While nearly all of the Alien and Sedition Acts expired a few years later, the Alien Enemies Act remains on the books today.)

Before the First World War began in 1914, civilian internment had been used as a tactic during a handful of colonial wars in Africa, the Pacific, and Cuba. As administered by Britain, Germany, Spain, and the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, colonial internment camps held the seeds of nearly everything the camps would become in the next hundred years, from sites of detention to factories of outright genocide.

Spain established the first camps in colonial Cuba in 1896. Rural populations were forced into urban camps to cut off guerrillas from local aid. Their crops burned and homes lost, families slowly starved to death on the outskirts of Havana and other cities. In the Philippines, five years later, the United States military briefly set up its own camps during a brutal campaign against independence fighters, executing civilians and waterboarding suspects during interrogations, actions considered so brutal that officers faced court-martial for their conduct. Between 1900 and 1902, the British would build more than a hundred camps to intern Afrikaner families and black Africans during the Anglo-Boer War in South Africa. As in Cuba, widespread mortality resulted more from poor planning rather than deliberate abuse, but this mismanagement caused tens of thousands of deaths. In 1904, Germany would incorporate concentration camps into a strategy of deliberate genocide against rebellious Herero and Nama tribes in its territory of South West Africa (today Namibia), driving them into the desert, hunting down survivors, chaining them together, and delivering them to labor camps with staggering mortality rates.

The death toll from colonial concentration camps ran to more than 150,000. Word of those fatalities, amplified by aggressive newspaper coverage and early human rights campaigners, turned the camps into a source of national shame for the imperial powers that had adopted them. In December 1904, Germany rescinded its extermination policy in South West Africa, and the Reichstag soon cut funding to the territory. In England during the Boer War, members of Parliament denounced the British military treatment of civilians, asking if the rules of civilized warfare agreed on in The Hague in 1899, the year the Boer War began, were being followed.

In the Anglo-Boer War, the British government argued the Hague Conventions did not apply: the Boer republics were not signatories. Nor did the Hague Conventions wield any meaningful force in relation to the treatment of prisoners in other colonial camps. Eventually ratified by more than forty nations, including Britain, Germany, Spain, and the United States, the conventions were binding only between signatories who later went to war with each other. The colonial camps were technically law-abiding. Colonial subjects and powers were not at war, only an indigenous people against their governors; the prisoners were natives, not enemy aliens.

Vaslav Nijinsky performing the “Siamese Dance” from the ballet Les Orientales, Paris, 1911. © Private Collection, Archives Charmet, Bridgeman Images. Photograph by Eugène Druet.

In the first days of the Great War, Britain intended only to detain suspect enemy aliens as prisoners of war. Pressured by Parliament to arrest all enemy aliens, British Home Secretary Reginald McKenna resisted, saying he would proceed under the Hague Conventions, in which the military was responsible for designating enemy aliens for arrest. Internment, he noted, was reserved only for enemy aliens who were military personnel or seen as dangerous to the nation. After the Lusitania’s sinking, however, the political resistance vanished, all military-age enemy aliens were rounded up, and civilians were transformed into prisoners of war.

As declarations of war multiplied across the globe between signatories of the Hague Conventions, a complex bureaucracy of detention began removing groups of civilians en masse from society. The Hague Conventions authorized internment of prisoners in a “town, fortress, camp, or other place,” but stated that they could “only be confined as an indispensable measure of safety.” At the heart of wartime internment conditions was the requirement that prisoners of war “be treated as regards board, lodging, and clothing on the same footing as the troops of the government which has captured them.”

To understand the effects of mass internment during the First World War, the experience described by Paul Cohen-Portheim should be multiplied hundreds of thousands of times around the globe. In November 1914, Germany moved to arrest all British, French, and Russian men between the ages of seventeen and fifty-five, and by war’s end held more than 111,000 enemy aliens. During the same period, France interned 60,000 German and Austro-Hungarian civilians; Bulgaria rounded up more than 14,000 Serbian and Croatian noncombatants; and Romania held 6,000 civilians, mostly Germans and Austro-Hungarians.

By the war’s end, concentration camps in Britain had housed more than 32,000 enemy aliens. In Russia, foreigners from Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey were exiled to villages in the far reaches of the tsar’s empire, with roughly 300,000 enemy aliens deported or interned before the Bolshevik Revolution led to a separate peace early in 1918. After joining the conflict in April 1917, the United States would intern just over 2,000 enemy aliens, nearly all of them Germans, with a twenty-two-year-old J. Edgar Hoover at the helm of enemy alien registration.

In an era of widespread conscription, any male of fighting age was a potential soldier. Generals worried that able-bodied foreigners deported to their home countries on one day might show up on the battlefield the next, further discouraging any desire to make distinctions between civilians and combatants. Internees knew that compared to life in the trenches, a concentration camp offered relative safety, but internment had its own price. Even where they had spent decades as part of a community, foreigners’ businesses were ransacked or shuttered, or their assets seized by governments. Internees were not soldiers, but instead a new kind of low-grade hostage. Not expected to fight or die, they only endured.

Do not do unto others as you would that they should do unto you. Their tastes may not be the same.

—George Bernard Shaw, 1903In all, records from the First World War document more than half a million civilian internees. Death, however, trumped detainment. During the war, Britain alone lost more than 700,000 soldiers in combat, and fatalities across the globe, civilian and military, have been estimated at over sixteen million. In the wake of this vast carnage, it is perhaps no wonder that the internment of a few hundred thousand enemy aliens has largely been forgotten. Yet the First World War was a watershed moment in the treatment of civilians during wartime. In the summer of 1914, concentration camps were a defunct, disgraced concept. By the end of the war, they stretched across six continents. In only four years, mass detention of innocent civilians had been legitimized in every corner of the earth.

The morning after his arrival at Knockaloe Internment Camp in May 1915, Cohen-Portheim listened to the camp commandant’s assurances that prisoners would be treated with kindness and consideration—his heart rose briefly—but if they tried to escape, the commandant continued, they could also be shot. Cohen-Portheim did not know it, but despite the rough aspects of the camp, it had been designed to preclude the kind of suffering internees had faced during the Boer War.

In the summer, prisoners could lie on a grassy hill and stare at the sky. In a camp with no adults over fifty or under eighteen, and no women at all, there were no obligations for internees beyond morning and evening roll call. Cohen-Portheim was prepared to make the best of circumstances for the week or two he thought might reasonably pass before his release.

As prisoners settled in, their belongings arrived, but one of Cohen-Portheim’s trunks had disappeared. The one he received was filled with the holiday gear he had optimistically packed: bathing attire, white flannel suits, and evening wear, but not a thing of any practical use. He began to wear his white suit regularly, to the amusement of fellow internees. He used his remaining money to acquire two nails to hang his clothes on and two boards for a headrest.

Cohen-Portheim’s lot improved further when he found he could receive not just letters from his family, but small sums of money as well. Class division reared its head when those with funds were allowed to request transfer to a “gentlemen’s camp” at Wakefield in West Yorkshire. Hearing of better conditions there, Cohen-Portheim signed on, only to find the same cramped quarters, the same boredom, and the same omnipresent barbed wire.

Newspapers criticized exemptions for influential foreigners, but internment affected all classes and occupations around the world. In 1915, as James Joyce began writing Ulysses, his brother Stanislaus—and nearly Joyce himself—was imprisoned in Austria as a subversive. Leon Trotsky was intercepted as he sailed from New York City on his way to Russia to greet the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. He was interned for several weeks as a political prisoner in a camp in Nova Scotia, despite the fact that Russia and Canada were not at war.

As the war dragged on and new camps were constructed around the world, an administrative bureaucracy also developed: POW information bureaus were set up; censors processed letters; complaints were received. Under the auspices of the Geneva Conventions, the Red Cross and neutral countries worked as go-betweens, forwarding packages and trying to broker prisoner exchanges. Red Cross officials alone visited more than five hundred camps in thirty-eight countries. As the administration of social quarantine flourished, camp libraries grew to thousands of volumes. Technical courses meeting professional guidelines were approved as trade certifications; prisoners could work toward qualification for Oxford or Cambridge upon release and, in some cases, even university degrees. But all these activities merely served as dressing on the open wound of endless imprisonment.

In February 1918, Paul Cohen-Portheim neared his third anniversary in prison. A year later, the diagnosis of “barbed-wire disease” would be offered by Swiss doctor and Red Cross observer Adolf Lukas Vischer to describe the effects of ongoing internment on civilians and combatants alike. “Try to imagine,” Cohen-Portheim wrote, “though it is impossible really to understand without having experienced it—what it means, never to be alone and never to know quiet, not for a minute, and to continue thus for years, and you will begin to wonder that there was no general outbreak of insanity.” Despite the absence of overt abuse in most camps, the combination of monotony, unknown release dates, lack of privacy, sexual deprivation, and prisoners’ helplessness to alter conditions combined to foster profound mental illness. Cohen-Portheim could not later recall a single prisoner entirely free of the ailment.

Early in the war, politicians had tried to carve distinctions between the “friendly alien” and the “enemy alien.” But the entire project of determining and assigning loyalties to people en masse was useless. For all the businesses closed, livelihoods wrecked, families sundered, and funds spent on camps, mass arrests of enemy aliens in Britain provided no discernible benefit. Heading into the Great War, Germany’s spy network was ineffectual, with Britain quickly rounding up known agents in the first days of the conflict. Not one German national living in Britain at the start of the war was linked to any wartime act of espionage.

Men dressed in traditional “straw boy” costumes, Ireland, 1922. Photograph by A. W. Cutler. Also known as “mummers,” straw boys traditionally provide merriment at weddings and other celebrations. The Secret Album of Europe, Volume 44 of The Secret Museum of Mankind.

Cohen-Portheim was released from prison in February 1918, when he was included in a prisoner exchange brokered by neutral Holland. Returning to Germany later that year, he found food scarce, the economy in ruins, and the country stumbling into civil war. Given how often circumstances belied his optimism, he proved shockingly fair in his depiction of his time in the camps. Time Stood Still was published in 1931, and the New York Times would later describe his memoir of internment as a civilian All Quiet on the Western Front.

In the rubble of a devastated Europe, however, there was little reflection on concentration camps. A few prisoners had rioted or been shot; camps in Canada and on the Eastern Front had controversially used forced labor; but for the most part the concentration camps could not compare to the unprecedented tragedy of modern warfare that had maimed, gassed, and killed millions. By 1918, the imprisonment of civilians seemed unexceptionable. The most humane parts of the camps—the Red Cross packages, the classes, the libraries, the orchestral performances—had normalized the idea of wartime internment.

The attempt to standardize and humanize internment conditions had also rehabilitated the idea of concentration camps and eroded memories of the brutality of the colonial camps. Indeed, once the public had adjusted to the idea of imprisoning innocent foreigners preemptively, governments learned how to harness anxiety of a foreign danger—with the underlying fear of crime, degeneracy, and disease—and assign it to other target groups, often domestic enemies. The identification of a pariah class, the registration and rules limiting conduct, followed by mass arrests and civilian detentions; the roll calls and prisoner numbers, the barracks, the watchtowers, the armed guards…civilians everywhere had experienced it all before as a seemingly necessary tragedy in the service of a national cause. Camps had become part of a formal process of dehumanization.

Leon Trotsky would record his own experiences in the Canadian concentration camp and write a memo in 1918 after his return to Russia, suggesting similar use of camps for enemies of the Revolution. Vladimir Lenin quickly embraced the concept, and orders went out to employ camps alongside executions as tools in the mass terror he aimed to instill. The system would find its champion under Stalin, whose Gulag rose in part on the back of Trotsky’s few unremarkable weeks in an internment camp in Nova Scotia.

If internment during the First World War provided some inspiration for the camps that preceded the Soviet Gulag, anti-Semitic measures in Germany, including the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, began in a way that felt even more familiar: the identification of an alien civilian population, followed by registration, restrictions, arrests, and detention in camps.

Yet even as reports of atrocities began to emerge in the 1930s, the world responded to the Nazi camps of the Second World War as if they were the internment camps of the First. In 1943, in the wake of the deportation of Danish Jews to the ghetto-camp at Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia, the king of Denmark insisted that Red Cross representatives be allowed to speak with prisoners there. The Final Solution was underway, but the Nazis needed to keep occupied countries from open revolt, and so permitted a visit. A preparatory frenzy of flower planting and renovation ensued, followed by faked cultural events—all contrived to display the familiar, suggesting that the camps of the Third Reich were no different from camps administered by other nations during the First World War.

Moroccan army of Caliph Umar al-Murtada routing the army of Emir Abu Yusuf at Marrakesh, from the Rico Codex, late thirteenth century. Cantigas de Santa Maria, by Alfonso X.

They were, of course, profoundly different, but each country in the Second World War transformed the concentration camps of the First into a machine that served its needs. British internment of enemy aliens in 1940 repeated the errors of haste and excessive arrests from 1915. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, the United States interned not only Japanese aliens, but nearly seventy thousand of its own citizens with Japanese ancestry. In occupied France during the Vichy era, French policemen rounded up alien Jews into camps, from which they were sent to Auschwitz. Russia deported hundreds of thousands of Poles eastward, many to Arctic labor camps. But none of these systems compared to the Nazi death camps that would establish concentration camps as the signature horror of the twentieth century.

Cohen-Portheim would not live to see the outbreak of another world war. He died in 1932, a year after the publication of his memoir and a year before Hitler’s rise to power. Of his years boarded among strangers with little hope for release, he wrote, “I cannot honestly say that it has harmed me.” But evaluating the moral nature of the camps, he was less accommodating. If the faceless standardization and dehumanization of concentration camps in the Great War had not done him permanent damage, he nonetheless saw himself as the atypical patient who comes out of an epidemic healthier than before. His own good fortune, he wrote, “must not prevent me from considering a disease a disease nor induce my readers to think that I call good what in itself is evil.”