People will not look forward to posterity who never look backward to their ancestors.

—Edmund Burke, 1790Magical Thinking

Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward presented a twentieth century that was free of nineteenth-century drudgery.

By Ben Tarnoff

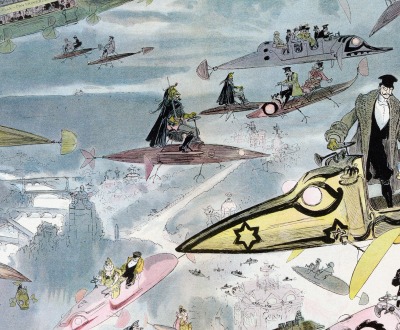

Le Sortie de l’opéra en l’an 2000, by Albert Robida, c. 1902. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Fiction rarely influences politics anymore, either because fewer people read it or because it has fewer things to say. Yet novels have affected America in large and unsubtle ways: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Jungle shaped the contours of the national current no less profoundly than our periodic wars and bank panics. More recently, Ayn Rand’s tales of triumphant individualism, Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead, inspired a resilient strain of free-market fundamentalism that continues to color our economic life. A Russian immigrant who adored her adopted country, Rand strove to become American in all things, and in the process became an especially American sort of storyteller: the kind whose stories are a means to a social or political end. It’s an honored tradition in American writing, one that acquits fiction of its perennial charge of uselessness by making it practical, identifying problems and offering solutions—pragmatic books for the purpose of the country’s self-improvement.

Few novels have sought to improve America as radically as Edward Bellamy’s bestseller Looking Backward, 2000–1887, published in 1888. Bellamy, like Rand, used fiction to popularize a philosophy, and with comparable results: Looking Backward sold nearly half a million copies in its first decade and appeared in several languages around the world. The book found many prominent admirers, among them

Mark Twain and William Jennings Bryan—the latter borrowed the language of his Cross of Gold speech from the novel’s final chapter. It inspired a political movement called Nationalism and energized generations of American progressives, from populists to New Dealers. More than a century later, it remains an indispensable zeitgeist book, an X-ray of the American body politic during the violent creation of modern industrial society, when many different futures felt possible.

Looking Backward is the story of Julian West, a wealthy young Bostonian who enters a hypnotist’s trance on May 30, 1887, and wakes up 113 years, three months, and eleven days later. Dr. Leete, an articulate citizen of the new century, greets him and explains, in the first of many leaps of logic required by the reader, that the hypnosis has perfectly preserved West’s body. He hasn’t aged an hour; Boston, however, has changed nearly beyond recognition. When West goes outside, he glimpses an idyll of tree-lined streets and majestic public buildings whose only familiar features are the Charles River and the islands of the harbor, gleaming through air clear of coal smoke.

Bizarre Figures, by Giovanni Battista Bracelli, 1624.

The following chapters consist mainly of expositive conversations between West and Dr. Leete—a technique beloved by science-fiction authors then and since—as the newcomer struggles to understand the enormous changes that have taken place since the nineteenth century. America is now a nearly perfect society. Prosperity is evenly distributed, people are highly educated, and crime, corruption, and poverty have disappeared. Humanity has reached “a new plane of existence.” Most miraculous is how this rebirth came about: through a bloodless social evolution, beginning in the late nineteenth century and concluding in the early twentieth. The industrial trusts of the 1880s were the first phase: they simply continued to consolidate until all of the country’s capital became the Great Trust—a single corporation, nationalized for the public benefit.

Predictably, West is skeptical. “Human nature itself must have changed very much,” he says. Not human nature, Dr. Leete replies, but “the conditions of human life,” as governed by the great social mechanism whose elaborate workings he spends the rest of the book patiently describing. As the nation is now the only employer, its citizens are its employees. For a term of twenty-four years, from ages twenty-one to forty-five, they serve in an “industrial army” that runs the economy. New recruits begin as common laborers before they select a profession; testing and training ensures that each finds the vocation best suited to his abilities. Compensation remains the same regardless of productivity, even for those too weak to work. This sum isn’t paid in dollar bills, but in nontransferable units allotted to each citizen’s “credit card,” exchangeable for clothing, food, and other necessities from state-run stores. Better workers are rewarded with promotion through the officer grades, ascending through a chain of command that culminates in the president of the United States. These positions confer prestige but hold little power. The system works like a perpetual-motion machine, with a minimum of human intervention.

Everyday life is more efficient and enjoyable, owing to a series of technological innovations. A nationwide network of pneumatic tubes provides for the rapid transport of goods. Music halls broadcast concerts by telephone directly into people’s homes. Housework has been abolished, liberating women from domestic drudgery. Electricity supplies heat and light, and the industrial army does everyone’s cooking and cleaning. When it rains, a single umbrella encloses the sidewalk, collectivizing a task once performed by thousands of private individuals—perhaps the book’s best metaphor for the contrast between the “barbarous” age of individualism and the enlightened present day.

Predictions of the future always carry the imprint of their present, which makes them useful for understanding the past. Science fiction in particular tends to betray its age as visibly as tree trunks or residual radiocarbon. An author may imagine inventions that fail to appear—pneumatic mail, for instance—but his deeper assumptions about the parameters of the possible are what date his work most strongly.

Looking Backward reads very differently today than it did when Bellamy wrote it. Its utopian premise strains under the sobering weight of the twentieth century—the real twentieth century, the century of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. The future produced nearly the opposite of what Bellamy had hoped. Large-scale social engineering led not only to utopian dreams but to genocides. Technology brought a better quality of life, but also made it easier to kill large numbers of people, whether with nuclear bombs or global warming. Bellamy expected moral progress to accelerate at the same rapid rate as science and industry; the last hundred years have made him look naive, even dystopian.

Yet what appears irrevocable in retrospect was anything but certain in 1888, and a vision that is eerily totalitarian today struck many Americans then as a plausible blueprint for a brighter tomorrow. Bellamy wasn’t blind to the inhumane aspects of modern industrial life. On the contrary: his book achieved popularity because it offered an elegant solution to the crisis of the late nineteenth century, when radically new forces remade a nation shattered by war, and set the tone for the social landscape we still live in.

The Civil War preserved the Union, and in the decades that followed, the American economy grew rapidly, sped by steam and steel. New technologies offered new opportunities to get rich, empowering a rising class of enterprising monopolists—men like Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie, and John D. Rockefeller, whose imperial accumulations of industry and infrastructure contrasted with the misery of the working poor who staffed their factories and furnaces and lived in slums. Many were recent immigrants; by 1880, more than a million industrial workers were children under the age of sixteen. An anemic political system, enfeebled by graft, did little to police the private sector, which periodically exploded in catastrophic financial panics. For members of Bellamy’s generation, the old principles and pieties inherited from their parents no longer applied; society had acquired a sharper edge, lacerated by antagonisms hardly imaginable before. Business and labor became bitter enemies. Wage cuts pushed more than a hundred thousand workers to join the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 before federal troops and state militia violently suppressed it, setting the pattern for many later clashes. In 1886, a bomb exploded at an anarchist labor rally in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, triggering a riot that fatally wounded at least twelve people. In the minds of many Americans, a toxic cast of characters had come to strut and fret their hour upon the public stage: venal politicians, vulturous capitalists, furious workers, murderous radicals. Democracy’s survival was an open question.

Everyone proposed a different solution. Quacks proliferated, peddling cure-alls. New ideas in philosophy, psychology, and social science made unorthodox thinkers like William Graham Sumner and William James nationally known. Henry Adams and Mark Twain pilloried the plutocracy; disciples of the nascent Social Gospel urged a society reorganized along Christian principles. Bellamy’s own politics drew upon several sources—Christianity, transcendentalism, and socialism, to name a few—but its origins lay in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts: the town where he grew up and later returned to settle. He recalled his boyhood home, in the years before its industrialization, as an American Eden: a classless, culturally cohesive community that suggests the Boston of Looking Backward. Then came the factories, and hordes of Irish immigrants to work in them. New sounds, smells, and sights bombarded the young Bellamy, traces of which surface in his fiction: “stenches,” “foul clothing,” the “perpetual clang and clash of machinery.” Born in 1850, he came of age with his country, and lost his innocence around the same time.

Bellamy’s personal past defined his proposed political future, a quality shared by an other eminent social prophet of the era, Henry George. Famous for his 1879 bestseller Progress and Poverty, George knew urban poverty firsthand as a struggling printer in San Francisco during the 1860s: for one impecunious period, he panhandled on the streets to feed his family. Turning to journalism, he observed a curious paradox. As the country became more prosperous, the rift between rich and poor grew. Land and capital tended to cluster at the top, making it harder for ordinary people to earn a decent living. Progress created poverty, and this counterintuitive insight formed the basis for his five-hundred-page treatise, which became a widely celebrated centerpiece of American socialism, blazing a progressive path through the dismal science of political economy and mobilizing the forces of reform much the way Looking Backward would nine years later.

“Flying Fireman,” color lithograph from the series Visions of the Year 2000, by Jean-Marc Côté, 1899.

For both Bellamy and George, a better future meant reconnecting with the country’s golden past, a sentiment shared by several generations of refbegan rmers and reactionaries since the early days of the republic. They longed to recover the lost legacy of the Revolution, the supreme moral heroism that inaugurated the American experiment.

They suffered from what might be called Founders nostalgia, a narrative of national decline that contrasts the impoverished present with the memory of American’s mythic creation. Americans had “drifted from their fast anchorage,” Bellamy wrote, gone adrift. The spirit of the Founders had been swept away by a torrent of thieves and speculators. Freedom now meant laissez-faire: the freedom to indulge in predatory accumulation, to exploit one’s fellow citizen. The ideals of the Revolution had been perverted to permit a buildup of power by the few—“despotism of the vilest and most degrading kind,” in George’s words—and this dictatorship of the rich posed as grave a threat to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as the British Crown had a century earlier. America needed to fulfill the promise of its founding by applying the principles of political democracy to its economic system. It needed to look backward and forward at the same time.

George found a remedy to return America to its democratic roots. He wanted to make land common property: not by collectivizing it, but by taxing its unimproved value—the value of empty land in its natural, undeveloped state. The “single tax” would curb speculation by eliminating the incentive to amass real estate for “nonproductive” purposes. Landowners would be forced to put their property to use: by building homes or factories, for example, thus lowering rents and creating jobs. Working would be rewarded; owning would be punished. George believed this would diminish the advantages of wealth and reverse the trend toward monopoly.

Bellamy drew the opposite conclusion. Rather than resist monopoly, he embraced it. Industrial capitalism produced more wealth more efficiently, he correctly observed. No other system could possibly satisfy “the demands of an age of steam and telegraphs and the gigantic scale of its enterprises,” as Dr. Leete explains in Looking Backward. At first those advantages exclusively benefitted the rich; soon they would come to benefit everyone. Civilization would outgrow inequality just as it had outgrown the handloom and the stagecoach. “All that society had to do was to recognize and cooperate with that evolution,” Dr. Leete explains, “when its tendency had become unmistakable.” Progress may bring poverty, but only as prelude to perfection.

Bellamy’s penchant for magical thinking began early in life. As a boy he read widely and expected a brilliant future, modeled along the lines of Napoleon, Muhammad, and Alexander the Great. Then he suffered a string of disappointments. Perpetually frail, he failed his physical exam at West Point, ending his dream of a career in the military. He enrolled in college, then dropped out; studied the law, gave it up. In 1871, at the age of twenty-one, he moved to New York City with the hopes of becoming a journalist. Even in his deepest gloom he felt glimmers of the self-confidence that would motivate his later writing. “Everyone to his taste,” he wrote, cloistered in his New York apartment, unnerved by the city’s bustle. “Mine runs rather to dreaming than to dollars, rather to fancy than fame. My mind to me a kingdom is, to which none other can bear comparison.”

It would be madness, and inconsistency, to suppose that things which have never yet been performed can be performed without employing some hitherto untried means.

—Francis Bacon, 1620The proclamation set the course for his career. After his brief stint in New York, he returned to Chicopee Falls, where he indulged his “reveries” by writing novels and short stories. He preferred to watch history unfold from a distance: “I can see such a situation clearer in my study than on the spot,” he said. If the isolation helped preserve Bellamy’s precarious health—tormented by tuberculosis, he fought a wasting disease and the attendant bouts of depression—it also gave his imagination freer reign. From his study, the world’s problems appeared very different than they did up close. What George saw as an economic problem, remediable by legislation, struck Bellamy as symptomatic of a broader moral malaise. The utopia he envisioned in Looking Backward provides not only a better quality of life, but a new mode of being. Its spiritual aspect is clear. As a young man Bellamy had defiantly embraced “dreaming” over “dollars,” and he made sure his ideal society filled both stomachs and souls. The Americans of Looking Backward unite in an economic, political, and spiritual union. They make society whole by merging their isolated selves. They achieve that American utopia first dreamt by John Winthrop when he promised to build a city upon a hill on the coast of Massachusetts Bay, and their earthly paradise owes much to the devout Protestantism of Bellamy’s parents and to the spiritual legacy of New England. It also reflects the tortured life of the author: a consumptive longing to escape his withering body, anticipating the millennial moment when his suffering and all suffering would be redeemed by the arrival of the New Earth. Looking Backward is a hymn to the democratic faith, a work of religious art that belongs alongside the sermons of Jonathan Edwards and the stained glass of John La Farge. What it lacks in literary merit it makes up in the scale and sincerity of its vision.

Ticknor and Company published Looking Backward in January 1888. The first “Bellamy Club” appeared that September. “Go ahead by all means,” Bellamy wrote to its founder, “and do it if you can find anybody to associate with.” Whether he considered his book a practical template for social change or what he once called “a fairy tale of social felicity”—he wavered on this point—he supported the movement it inspired with as much enthusiasm as his deteriorating health would allow. He named his system Nationalism, by which he meant the absorption of industry by the “national organism” for the purposes of economic equality. As sales of Looking Backward soared, Nationalist clubs sprouted across the country—there were 165 by early 1891—and two periodicals, the Nationalist and The New Nation, began circulating.

The notion that the problems of industrial capitalism would solve themselves—that the riddle, as Dr. Leete says, would provide its own answer—held a mystical appeal for many Americans. Bellamy advocated the conciliation of all classes without conflict. This demonized no single group and, crucially, absolved everyone of responsibility. Neither the capitalists nor the workers could be blamed; both performed their appointed roles as if guided by an invisible hand. The alchemy of this logic—its transmutation of a dismal present into a golden future—spoke strongly to the irrational needs of the American political soul, to its enduring love of magic over reason.

“The Evening,” right panel from the triptych The Golden Age, by Léon Fréderic, 1901.

Despite its popularity, Nationalism didn’t resonate with everyone. Its adherents came disproportionately from the middle class. They were doctors, lawyers, and priests. Like Bellamy, they were neither rich nor poor but somewhere in between. If they didn’t live as luxuriously as the robber barons, at least they didn’t have to endure the wretched wage-slavery of the factories and farms. They shopped in department stores and served on school boards. They hewed closely to Victorian tastes in clothing, courtship, and art. They were the “gentry” lampooned in Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad, the forerunners of George Babbitt, Rabbit Angstrom, and other Middle Americans. Looking Backward made sense to them because it projected a future not so much classless as monolithically middle class.

This explains the oddly preindustrial universe of Looking Backward. Loud, loutish workers of the sort that invaded the Chicopee Falls of Bellamy’s childhood are conspicuously absent. A factory never appears. Boston is bucolic, its citizens bourgeois. Their style of speech and sense of decorum has hardly changed since the nineteenth century. Dr. Leete’s daughter Edith obeys every convention of Victorian womanhood: tenderhearted, tearful. The courtship scenes between her and West, as they fall hopelessly in love, enact a ritual as bizarre to contemporary readers as bundling or barn raising—one encoded in the rules of sentimental romance, a popular genre among Bellamy’s middle-class readership.

Americans loved Looking Backward not only for its simplicity but also for its sentiment. By writing a novel with sympathetic characters, a love story, and a clear narrative arc, Bellamy gave his ideas an emotional momentum that sped their entry into the real world. What Looking Backward conveys, despite its limitless appetite for logistical detail and language that often veers from wooden to limp, is above all a feeling, a mood, the hard-won optimism of Bellamy himself, patiently awaiting the day “when heroes burst the barred gate of the future.” On how to hasten this future’s arrival, however, the book says little. A reader of Progress and Poverty could join George’s crusade for the single tax. A reader of Looking Backward found himself in the peculiar position of knowing the destination without having the least idea how to get there. This boosted its popular appeal and doomed its political future. The Nationalists supported reformist candidates and campaigned for public ownership of utilities, but these seemed relatively small-bore compared with the wholesale spiritual renewal envisaged by Bellamy. Exactly how and when this transformation would come about, no one knew.

Perhaps they lost patience, or turned to more practical pursuits. From its peak in the early 1890s, Nationalism steadily declined. By the time he published a sequel in 1897 called Equality, Bellamy no longer had the strength to lead his people to the promised land. As the tuberculosis wracked and shriveled his body, he confined himself to his bedroom in Chicopee Falls, accompanied only by his wife. “After all, dying is only moving into the next room,” he told her, a few hours before making his exit.

Bellamy believed that the valved, vaned leviathan that annihilated the past and annexed his hometown of Chicopee Falls with its factories could eventually create a better society. One hundred and twenty-three years later, those factories have come and gone, but many of the problems remain the same. The twenty-first century bears little resemblance to Bellamy’s future; the closer comparison would be to his present, to the late nineteenth century that the hero of his novel happily escapes. This was a society defined by tremendous income inequality, financial uncertainty, sleazy politics—in other words, much like our own. The contradictions of modern capitalism haven’t resolved themselves, as Bellamy assumed. Rather, they’ve become deeply embedded in American life, and the new economic world created after the Civil War has come to feel so natural, so inescapable, that even many of its staunchest critics have trouble imagining an alternative.

In 2011 inequality continues to grow, and the gulf between American rhetoric and reality, between the idea that all men are created equal and the hardening aristocracy of privilege and wealth, has become so familiar as to be almost invisible. The richest one percent now earn almost a quarter of the nation’s total income and own nearly half of the financial wealth. Economic growth since 1980 has overwhelmingly benefitted that top percentile, and tax cuts have helped preserve the disparity. The crisis of the late nineteenth century has been preserved nearly as perfectly as Julian West’s hypnotized body, awaiting another Bellamy to offer an escape route from the moral cul-de-sac of American capitalism.

For all his faults, Bellamy understood that telling stories, and not citing statistics, is what motivates change. He made a complex situation intelligible through narrative. He showed how society’s moving parts connected, and how their motion might be directed toward a higher purpose. If much of his novel is dated, it also expresses a breadth of imagination entirely absent from today’s politics, and a creative faith in the future that can’t fail to make one nostalgic.