Refrigerators and television sets, or even rockets sent to the moon, do not change man into God.

—Czesław Miłosz, 1960Isolation Booth

E.M. Forster on Zoom.

Imagine, if you can, a small room, hexagonal in shape like the cell of a bee. It is lit neither by window nor by lamp, yet it is filled with a soft radiance. There are no apertures for ventilation, yet the air is fresh.

There are no musical instruments, and yet at the moment that my meditation opens, this room is throbbing with melodious sounds. An armchair is in the center, by its side a reading desk—that is all the furniture. And in the armchair there sits a swaddled lump of flesh—a woman, about five feet high, with a face as white as a fungus. It is to her that the little room belongs.

An electric bell rang.

The woman touched a switch, and the music was silent.

“I suppose I must see who it is,” she thought and set her chair in motion. The chair, like the music, was worked by machinery, and it rolled her to the other side of the room, where the bell still rang importunately.

“Who is it?” she called. Her voice was irritable, for she had been interrupted often since the music began. She knew several thousand people; in certain directions human intercourse had advanced enormously.

But when she listened into the receiver, her white face wrinkled into smiles, and she said, “Very well. Let us talk, I will isolate myself. I do not expect anything important will happen for the next five minutes—for I can give you fully five minutes, Kuno. Then I must deliver my lecture on ‘Music During the Australian Period.’ ”

She touched the isolation knob, so that no one else could speak to her. Then she touched the lighting apparatus, and the little room was plunged into darkness.

“I have called you before, Mother, but you were always busy or isolated. I have something particular to say.”

“What is it, dearest boy? Be quick. Why could you not send it by pneumatic post?”

“Because I prefer saying such a thing. I want—”

“Well?”

“I want you to come and see me.”

Vashti watched his face in the blue plate.

“But I can see you!” she exclaimed. “What more do you want?”

“I want to see you not through the Machine,” said Kuno. “I want to speak to you not through the wearisome Machine.”

“Oh, hush!” said his mother, vaguely shocked. “You mustn’t say anything against the Machine.”

“Why not?”

“One mustn’t.”

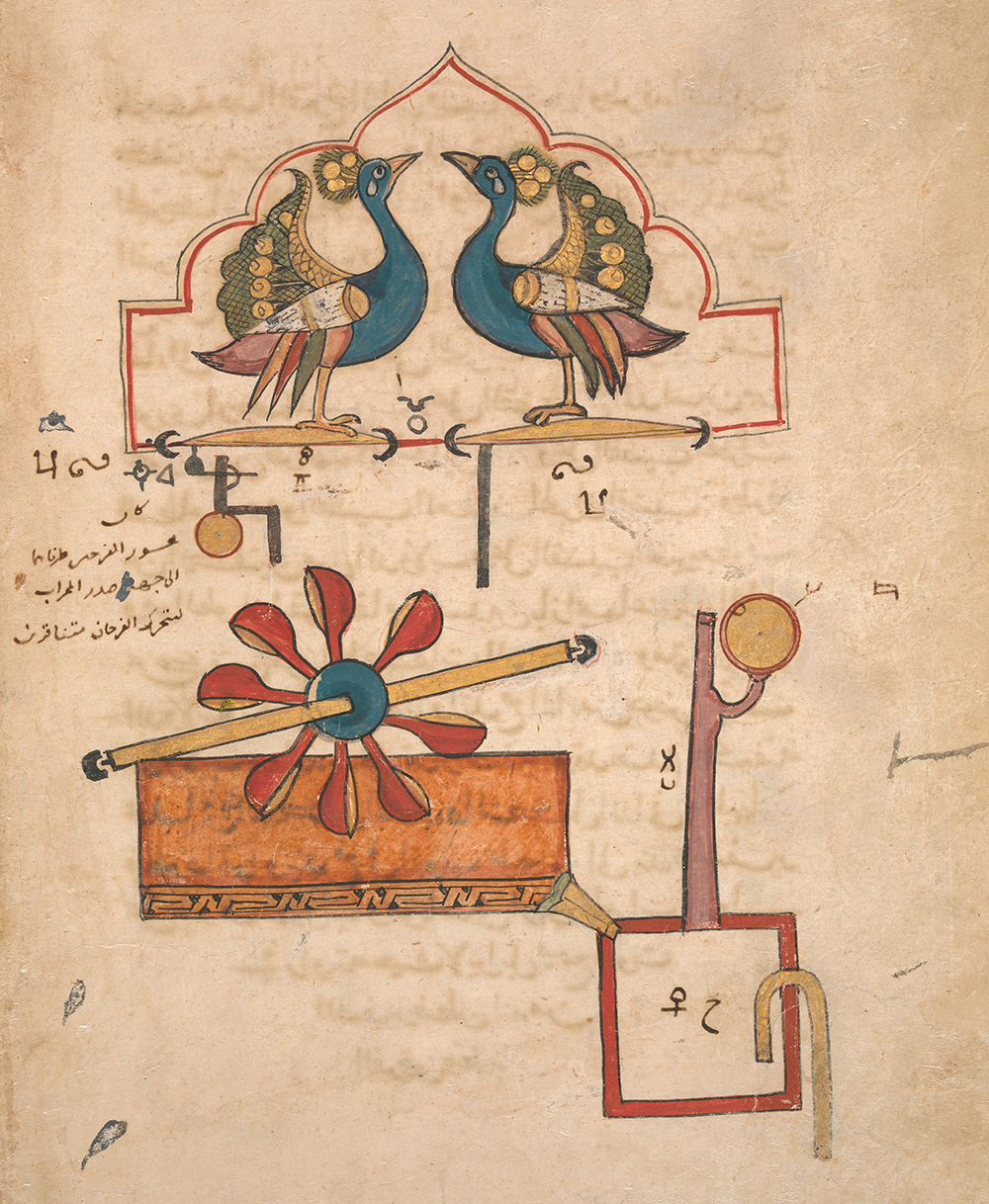

Water Clock of the Peacocks, miniature from a 1315 edition of al-Jazari’s Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1955.

“You talk as if a god had made the Machine,” cried the other. “I believe that you pray to it when you are unhappy. Men made it, do not forget that. Great men, but men. The Machine is much, but it is not everything. I see something like you in this plate, but I do not see you. I hear something like you through this telephone, but I do not hear you. That is why I want you to come. Come and stop with me. Pay me a visit, so that we can meet face-to-face and talk about the hopes that are in my mind.”

She replied that she could scarcely spare the time for a visit.

“The airship barely takes two days to fly between me and you.”

“I dislike airships.”

“Why?”

“I dislike seeing the horrible brown earth, and the sea, and the stars when it is dark. I get no ideas in an airship.”

“I do not get them anywhere else.”

“What kind of ideas can the air give you?”

He paused for an instant.

“Do you not know four big stars that form an oblong, and three stars close together in the middle of the oblong, and hanging from these stars, three other stars?”

“No, I do not. I dislike the stars. But did they give you an idea? How interesting; tell me.”

“I had an idea that they were like a man.”

“I do not understand.”

“The four big stars are the man’s shoulders and his knees. The three stars in the middle are like the belts that men wore once, and the three stars hanging are like a sword.”

“A sword?”

“Men carried swords about with them, to kill animals and other men.”

“It does not strike me as a very good idea, but it is certainly original. When did it come to you first?”

“In the airship—” He broke off, and she fancied that he looked sad. She could not be sure, for the Machine did not transmit nuances of expression. It only gave a general idea of people—an idea that was good enough for all practical purposes, Vashti thought. The imponderable bloom, declared by a discredited philosophy to be the actual essence of intercourse, was rightly ignored by the Machine, just as the imponderable bloom of the grape was ignored by the manufacturers of artificial fruit. Something “good enough” had long since been accepted by our race.

“The truth is,” he continued, “that I want to see these stars again. They are curious stars. I want to see them not from the airship but from the surface of the earth, as our ancestors did thousands of years ago. I want to visit the surface of the earth.”

She was shocked again.

“Mother, you must come, if only to explain to me what is the harm of visiting the surface of the earth.”

“No harm,” she replied, controlling herself. “But no advantage. The surface of the earth is only dust and mud, no life remains on it, and you would need a respirator, or the cold of the outer air would kill you. One dies immediately in the outer air.”

“I know. Of course I shall take all precautions.”

“And besides—”

“Well?”

She considered, and chose her words with care. Her son had a queer temper, and she wished to dissuade him from the expedition.

“It is contrary to the spirit of the age,” she asserted.

“Do you mean by that, contrary to the Machine?”

“In a sense, but—”

His image in the blue plate faded.

“Kuno!”

He had isolated himself.

For a moment Vashti felt lonely.

Then she generated the light, and the sight of her room, flooded with radiance and studded with electric buttons, revived her. There were buttons and switches everywhere—buttons to call for food, for music, for clothing. There was the hot-bath button, by pressure of which a basin of (imitation) marble rose out of the floor, filled to the brim with a warm deodorized liquid. There was the cold-bath button. There was the button that produced literature. And there were, of course, the buttons by which she communicated with her friends. The room, though it contained nothing, was in touch with all that she cared for in the world.

Tools belonging to firearms engraver Louis D. Nimschke, United States, late nineteenth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of the Robert M. Lee Foundation, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th anniversary, 2018.

Vashti’s next move was to turn off the isolation switch, and all the accumulations of the last three minutes burst upon her. The room was filled with the noise of bells and speaking tubes. What was the new food like? Could she recommend it? Had she had any ideas lately? Might one tell her one’s own ideas? Would she make an engagement to visit the public nurseries at an early date—say this day month?

To most of these questions, she replied with irritation—a growing quality in that accelerated age. She said that the new food was horrible. That she could not visit the public nurseries through press of engagements. That she had no ideas of her own but had just been told one—that four stars and three in the middle were like a man; she doubted there was much in it. Then she switched off her correspondents, for it was time to deliver her lecture on Australian music.

The clumsy system of public gatherings had been long since abandoned. Neither Vashti nor her audience stirred from their rooms. Seated in her armchair she spoke, while they in their armchairs heard her, fairly well, and saw her, fairly well. She opened with a humorous account of music in the pre-Mongolian epoch and went on to describe the great outburst of song that followed the Chinese conquest. Remote and primeval as were the methods of I-San-So and the Brisbane school, she yet felt (she said) that study of them might repay the musician of today: they had freshness; they had, above all, ideas.

Her lecture, which lasted ten minutes, was well received, and at its conclusion, she and many of her audience listened to a lecture on the sea. There were ideas to be got from the sea; the speaker had donned a respirator and visited it lately. Then she fed, talked to many friends, had a bath, talked again, and summoned her bed.

E.M. Forster

From “The Machine Stops.” Published in 1909, between A Room with a View and Howard’s End, this short story “is not simply prescient,” commented the art critic Will Gompertz. “It is a jaw-droppingly, gobsmackingly, breathtakingly accurate literary description of lockdown life in 2020.” A member of the Bloomsbury literary group, Forster shared a close relationship with Virginia Woolf, about whom he delivered a Rede Lecture after her death. “He says the simple things that clever people don’t say,” Woolf wrote of Forster in her diary. “I find him the best of critics for that reason.”