People commonly travel the world over to see rivers and mountains, new stars, garish birds, freak fish, grotesque breeds of human; they fall into an animal stupor that gapes at existence, and they think they have seen something.

—Søren Kierkegaard, 1843Take Nothing, Leave Nothing

How I came to be banned from the world’s most remote island, Tristan da Cunha.

By Simon Winchester

British overseas territory Tristan da Cunha, 2012. Photograph by Brian Gratwicke.

Seventeen hundred miles from what is customarily called civilization—in this case, the western shore of the Republic of South Africa—lies a tiny British-run volcanic island populated by fewer than three hundred people who lay claim to living in the most isolated permanent habitation in the world.

I am presently sitting five cables off this island, Tristan da Cunha, wallowing on the swells on a small boat that is hove-to just off the mole at the entrance to the harbor of Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, the island’s capital and only settlement. But while my fellow passengers will soon be landing—once the easterly gale blows itself out and the seas die down to an acceptable level—and so are excitedly preparing themselves to enjoy the fascinations that Edinburgh has in store (a visit to the fields where the islanders grow potatoes being the main advertised attraction), I will not be joining them.

For I have been sternly and staunchly forbidden to land. The Island Council of this half-forgotten outpost of the remaining British Empire has for the last quarter century declared me a Banned Person. I am welcome on Tristan neither today nor, indeed, as was succinctly put to me in a diplomatic telegram last year, “ever.”

It would be idle to suggest that I have been terribly incommoded. Though some may suspect sour grapes, I have to confess that there is little of great charm to Tristan. Such as it possesses derives almost entirely from its status: there is a very large hand-painted sign in the Edinburgh square saying, welcome to the remotest island, and once our visitors have had themselves photographed beside it, have exchanged pleasantries with various islanders over warm English beer at the rather underdecorated Albatross Pub, have studied the piles of canned pork sausages and sugar-rich candies on sale in the cinder-block shop, and have made the obligatory two-mile pilgrimage (on the island’s only road) to the fields where the potatoes grow, most will be eager to return to their waiting cruise ship, to wonder as the island fades away astern, why on earth anyone would wish to live there.

The latest census says that 275 people do. They belong to just seven eternally intermarrying families. Two of the families are the descendants of the civilian support staff of a military garrison that Britain established on the island in 1815 to help ward off any French loyalists who might try to rescue Napoleon from St. Helena, 1,500 miles to the north. An Italian ship was later wrecked on the island, bringing with it two further surnames. Two more family names came down from passing American whalers and one from a similarly wandering Dutchman, expanding a gene pool which remains to this day severely limited—and is said to be responsible for the curious similarity of the islanders’ appearances, and the numerous cases of asthma, retinitis pigmentosa, and other genetically influenced ailments that afflict the population.

Odysseus and his companions passing the Isle of the Sirens, Roman mosaic, third century. Bardo Museum, Tunis, Tunisia.

Utter isolation—just a scattering of supply ships and randomly appearing cruise liners happen by each year; there is no airfield—instills a healthy self-reliance into what is in any case a very singular culture. The men fish for lobster (a pair of which appear on the islands’ coat of arms), tinker with their boat engines, tend the herd of cattle and flock of sheep, dig the vegetable patches; the women knit (large woolen sweaters called “ganzeys,” socks to be put inside sea boots called “ammunitions”), perform most of the island paperwork, organize regular morale-lifting celebrations.

The older islanders incorporate nineteenth-century “thees” and “thous” into their speech—on hearing such chatter it seems perfectly reasonable that only sixty years ago all trade was performed by barter: to send a letter to England cost five potatoes. And though satellites have had their recent effect, it seems understandable, too, that until thirty years ago all contact with the outside world was by Morse code—fitful, unreliable, and subject to the vagaries of the ionosphere.

But London keeps its eye on this far corner of the Empire. Two British diplomats preside—colonial figures hardly cut from the same cloth as the old viceroys of India or governors of Nigeria or Hong Kong. The senior man is usually on the verge of retirement, having enjoyed rather too little distinction in his career, or else sporting a stated fascination with birdwatching, since there is a local and much celebrated albatross. His assistant is invariably an eager youngster—on this occasion an ambitious young woman who was leaving after six months for a long-sought and career-boosting posting outside Kandahar. There is usually rather little for the pair to do: the only signed order currently posted on the island’s official notice board refers to a power cut due for two hours the following Tuesday.

Once in a long while, though, there is a crisis. The event for which Tristan is perhaps best remembered was the eruption of its volcano in 1961, and the evacuation of the entire population. The 264 islanders—the population size has remained very stable for the last half century—were brought to England and put up in a disused army barracks in Hampshire. But the supposed delights of Western civilization—cars, elevators, cinemas, none of which the islanders had ever seen before—did not seduce them into staying: two years later all but fourteen went home. They rebuilt their ruined town and settled back to their uncomplicated routines of fishing for lobsters and knitting ganzeys. The Daily Mirror of the time said, admiringly, that by doing so the islanders had delivered to all smug Britons a much deserved and contemptuous slap.

I first went to the island in 1983, then again a little later. I was welcomed, though warily: the self-reliance of the islanders is matched by a fierce devotion to self-protection and privacy. They knew I was a writer: they warned me that anything I might publish would be read and analyzed for years to come. And though nothing untoward occurred while I was visiting (my time ashore I spent fully impressed with the idea of leaving only footprints and taking only snapshots) it was shortly after that second trip that I quite inadvertently committed the indiscretion which resulted in my lifetime prohibition.

At first blush it all sounds to have been innocent indeed. It stems from a somewhat bizarre British government decision, taken during World War II, to reclassify some of its more remote island possessions as ships. Tristan was transmuted into HMS Atlantic Isle, and its role was to patrol (from its rock-hewn state of immobility) for any German U-boats that might be lurking in the southern Atlantic. To compound the fantasy a small party of sailors was posted there to man the ship—one of them a young and apparently romantically minded lieutenant and littérateur manqué named Derrick Booy.

In the grand tradition that has long intertwined nice girls and sailors, Lieutenant Booy fell for one of the island’s prettiest, a slip of a lass then named Emily Hagan. He stayed only eighteen months on the island, and once the war was over he wrote a memoir, published in 1957. In it he made many tender mentions of Miss Hagan, and though his writings leave little doubt as to his own feelings, they are somewhat ambiguous as to the degree that his ardor was reciprocated.

Two paragraphs stood out as most pertinent. One recorded the pair’s first meeting:

The night air was an enveloping golden presence as we stood at the break in the wall. I was conscious of bare, rounded arms and the fragrance of thickly clustered hair. The lingering day was full of noises. As the sky darkened to a deep, umbrageous blue, speckled with starlight, and the village was swallowed by darkness at the foot of the mountain, from somewhere in that blackness came the throaty plaint of an old sheep, like a voice from the mountain. From that other obscurity, silver-gleaming below the cliffs, came the muttered irony of the surf. The girl waited only a few minutes before her full lips breathed “Goodnight,” and she slipped toward the house. “Shall I come to see you again?” I called softly. She may or may not have answered “Yes.” If she did, it was probably from politeness.

And the other notes the mechanics of their eventual parting, recorded after Lieutenant Booy had boarded the whaler that would take him out to his waiting navy ship, and away.

The watchers on the beach were all very still, the women sitting again in their gaily dressed rows, as if waiting primly to be photographed. None of them waved or cheered. They just sat watching. All looked very much alike, young and old. But there was one at the end of a row, in a white dress with a red kerchief, bright-red over smooth, dark hair. She sat perfectly still, staring back until she became a white blur. Then her head went down, and the woman behind her—a large one in widow’s black—put a hand on her shoulder.

Whatever her feelings for the jolly Jack tar, ten years later Emily Hagan was married to Kenneth Rogers, an islander who had been employed as a mess boy by the visiting naval party, and who after the war worked both as the island’s baker and a butcher. By the time I got to Tristan he was in his sixties, working as a part-time assistant barman at the Albatross. But the very moment I fetched up outside his tiny thatched cottage, notebook in hand, he knew exactly what I wanted. “To see our H’em’ly, I suppose,” he said, glumly. He knew just why. He didn’t want to let me see her. He placed himself four-square behind his garden gate, keeping it firmly latched.

The Argonauts, by Lorenzo Costa, c. 1488. Museo Civico, Padua, Italy.

He gave me a stern lecture, all the more touching by being couched in his elegant and ancient English. He said he wished I would purge from my mind all that I had read in the “navy man’s” book. The revelations, he said, had “hurt us all. It was all a long, long time ago, and we’d just as soon forget it.” He was courteous, kindly, firm. And two days later, just before I left the island for good, he came down the harbor to see me off. “Remember,” he said, “whatever you write will last for years; we back on the island will pore over it and analyze it a thousand times. Be careful what you write—for our own sakes.”

But I have to confess that, when it came to writing, I ignored him. I began work on a book about all of the remaining outposts of the British Empire—for my visit to Tristan was but part of two long years of wanderings that took me from Pitcairn to Diego Garcia, from Bermuda to the Falkland Islands, from Hong Kong to Gibraltar, and to all those other weather-beaten relics of Imperial Britannia. When I came to the Tristan chapter, I decided that I would in fact tell the story of Emily Hagan and Derrick Booy, in full.

It would be a very small part of a story about a very small island in an overlooked corner of the world. But as a story it was a good one—especially if I quoted from his book Derrick Booy’s two rather overwrought paragraphs. My rationale for doing so was simple: everything had already been made public; everything was in the prints; and in any case the story, told in an exquisitely gentle fashion, was just a near-beer account of a wartime love affair which, by all accounts, had been tender, unconsummated, and quite possibly entirely imagined. I thought that back on a Tristan which now seemed a very, very long way away, old Kenneth Rogers was being just too, too sensitive: the story was the thing, that was all there was to it. So I wrote the book; it was duly published. The reviews were kindly, the sales modest—and I thought little more of it.

Except that twelve years passed, and then out of the blue in 1998 I was invited onto a cruise ship on passage through the Southern Ocean. I had been asked to go along to talk to the passengers about various places I had visited: the Antarctic, South Georgia, Gough Island, Inaccessible, Nightingale—and Tristan. I did as I was bidden, without incident for the first two weeks of the voyage. Then on a Friday morning, during a half gale just north of the Antarctic convergence, I gave my talk about the history of Tristan. We arrived the following evening, and when we were comfortably at anchor off the Edinburgh mole, we were boarded, somewhat surprisingly, by a very large imperial policeman. He had a brief announcement to make: everyone would be permitted onto the island the following morning, but regrettably not—the ship’s passenger manifest had been radioed ahead—Mr. Winchester.

I had, he explained sternly, betrayed an island secret. I had been warned; I had actually been implored. But I had gone ahead, and now the islanders were every bit as hurt and upset as Kenneth Rogers had forewarned. The constable was implacable, immovable. And so the passengers, most of them greatly amused, filed past me down to the gangway, boarded their Zodiacs, and were swept off behind the riprap into Calshot Harbor—named for the village in Hampshire to where the islanders had been evacuated in 1961—and off to see the sights of Edinburgh. When they returned an hour or so later they shook their heads as one: why would anyone want to live there? And then they puzzled over my exclusion: it’s not as though you had killed someone.

Another invitation, from a second cruise line, dropped through the mailbox in the spring of 2008: it was for a voyage due to begin in the austral autumn of 2009, in March. This time, anticipating problems, I wired ahead. I asked the British chief resident envoy to Tristan, David Morley (whose career path had previously included postings to such out-of-the-way legations as Kaduna, Mbabane, and Port Stanley) if I were still banned. Surely not, I said I supposed. Twenty-four years had passed. Emily and Kenneth Rogers were now both dead. Surely by now I had purged my contempt?

Weeks passed until his telegram of reply. Sadly no, he finally reported. The Island Council had met, had formally considered the request, and had voted that, “You will not be able to land on this occasion or, indeed, ever.”

And so with that knowledge I boarded the MY Corinthian II (in Ushuaia, in southern Patagonia, a town where I had once spent three months in prison on spying charges during the Falklands War, but which by contrast still welcomes me warmly each time I happen by), and off we sailed, along the familiar sub-Antarctic milk run. I delivered without incident my lectures about the Falklands, on South Georgia, on the history of the Atlantic—and eventually, about Tristan da Cunha. And it was then that I told the passengers that I would not be going with them, and explained why.

By now I had built up something of a rapport with the passengers, and a gasp went up. Most seemed quite incredulous. Nearly all were American. Many happened to be lawyers. These last were especially exasperated on my behalf. Over dinner later they insisted that I sue. Freedom of speech, they chorused. Moreover—Tristan is British, and you are British: it isn’t even an immigration question. It is a simple assault on free speech. A village in Yorkshire, said one attorney who had spent time there, would not legally be able to ban someone from visiting because he had written that the village was ugly, or the inhabitants were unpleasant, or that the publican was having an affair with the vicar’s wife. So sue! Go to the Tristan High Court! The St. Helena High Court! The House of Lords! You’ll be bound to win. No problem!

I let the passengers press past me once again on their way down onto the gangway, and I watched with some melancholy as they filed into the Zodiacs. I stood on the bridge with the lugubrious German captain and borrowed his binoculars to watch the tourists make their way to the Albatross, to the slopes of the volcano, to the church, to the potato fields. And then I went back to my cabin, and for the next few irritating hours pondered my fate and thought about travel in general, and about such weighty matters as the sayings of Blaise Pascal, who once infamously wrote that all of mankind’s ills stemmed from his inability to remain peacefully at home in his living room. Then as dusk was falling, I emerged back onto the deck to greet the returning scrum.

And I found that I had in those few hours become both contrite, and a convert. Pascal, I concluded, had a point. I was now in fact quite certain that, whatever high principle might be involved, the islanders of Tristan were in fact quite right and I, as a clumsily meandering and utterly thoughtless outsider, was very, very wrong indeed.

For though I sedulously followed the rule of taking nothing and leaving nothing, it suddenly seemed to me that my very being on the island, and my later decision to record my impressions of that visit and the impressions of earlier visitors, had resulted in a series of entirely unintended and unanticipated consequences—consequences that were as inimical to the islanders’ contentment as if I had plundered or polluted there.

I had no understanding whatsoever that by repeating that naval officer’s memoir, I could hurt the feelings of anyone. To my clumsy, unthinking, touristic mind, the notion seemed quite absurd. To be sure, old Kenneth Rogers had explained it to me kindly—but I had chosen to ignore his warning, to dismiss his assertion of feeling. I had failed, even for one second, to consider what he and his fellow islanders might think—because I held to an unspoken assumption that as a visitor from the sophisticated outside, I knew better, and that I had something of a prescriptive right to do with him and his like, more or less as I pleased. (Repeating it here, a second time, as a didactic exercise, seems unlikely to compound the felony: even as he told of the renewed ban, the island constable who boarded our vessel assured me that few of the younger islanders now minded, and only a very small number even remembered. “And if it were up to me, I’d let you back.”)

Then came a cascade of similar memories, from earlier journeys. The woman from San Diego whom I met in a truly remote Amazon village, buying up everything she could see—a volcano-sized pile of old chairs and tables and statuettes assembled on raffia mats in the village square, the villagers looking on in eager anticipation of their good fortune from the sale of their castoffs—but who promptly walked out on the deal when told that the village had no facility for taking her Visa card. The Microsoft billionaire who arrived on Namibia’s Skeleton Coast with five helicopters full of bodyguards, and demanded that all available local lions be collected in one oasis so that he could see and picture them. The Texan who insisted on being pictured beside his golf club’s pennant on every Arctic and Antarctic stop he made, then teeing off and driving one ball—such a little ball, he would sweetly insist—into the sea.

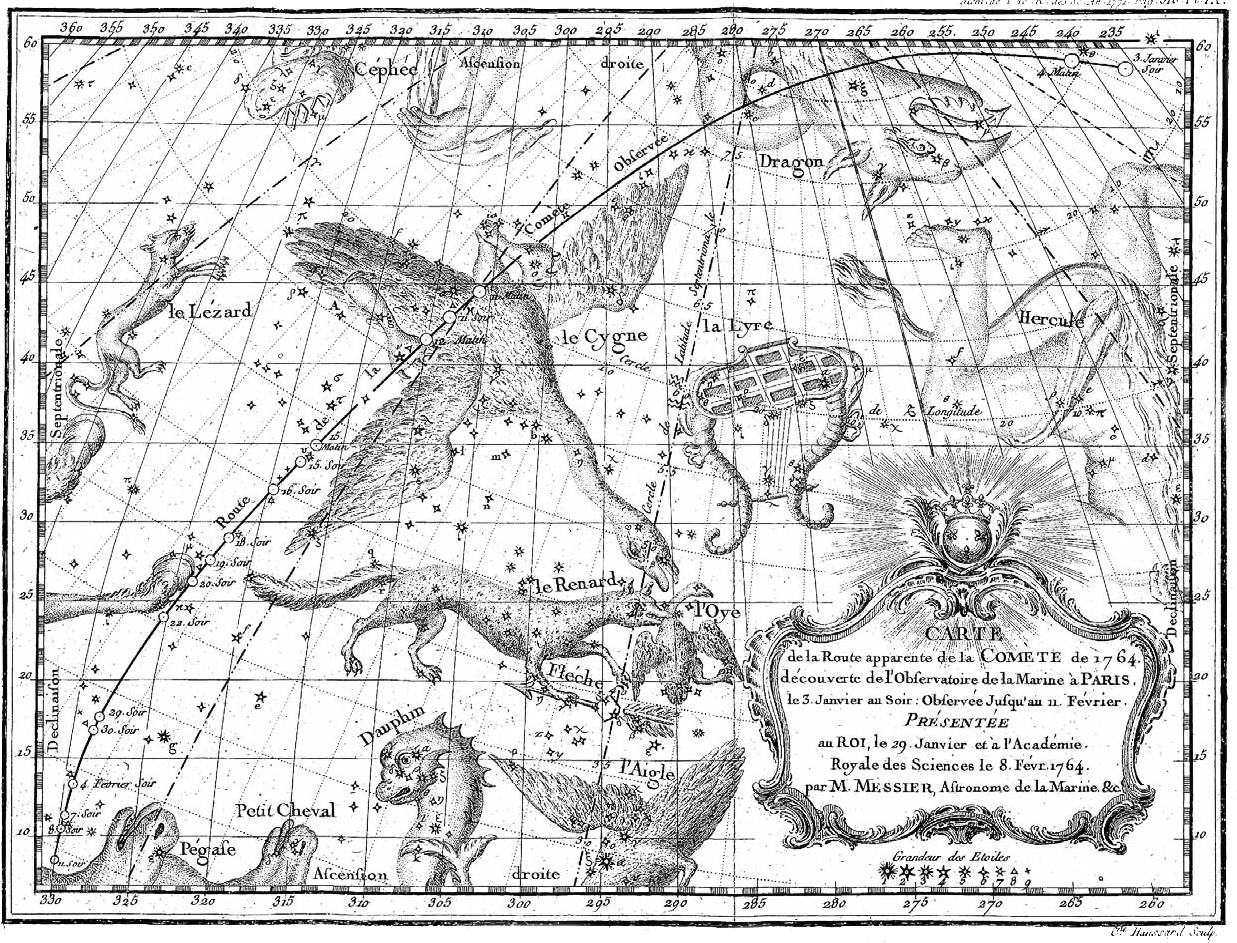

Star chart with the route of the 1764 comet, by Charles Messier, 1764.

We have an unceasing capacity to make ourselves nuisances, basically. Students of tourism science can and do construct elaborate theories from physics, of course, invoking such wizards as Heisenberg and the Hawthorne effect and the status of Schrödinger’s cat to explain the complex interactions between our status as tourist-observers and the changes we prompt in the peoples and places we go off to observe. But at its base is the simple fact that in so many instances, we simply behave abroad in manners we would never permit at home: we impose, we interfere, we condescend, we breach codes, we reveal secrets. And by doing so we leave behind much more than footfalls. We leave bruised feelings, bad taste, hurt, long memories.

Attractive-sounding mantras about footprints and photographs won’t fully resolve the problem. The only real solution, however impractical and improbable, is to hearken to Pascal’s much scorned adage, to resolve to resist the blandishments of the brochure, and stay away. Certainly the people of Tristan da Cunha would have been happier had I stayed back—and who would deny the rights of the people of Tristan, just as ourselves, to be left happy, and at peace?

Except that in the specific case of Tristan da Cunha, it is probably too late. The island has recently appointed a government tourist officer, and the community’s leadership has recently come formally to accept—rather later than most other places—that catering to the visiting curious is quite a reliable way of making what, back in the barter days of sixty years ago, most Tristanians knew little about—money. Tourism for the islanders, it was argued in Council, has the advantage of being less hazardous a road to riches than rowing out to catch lobsters, and a good deal more profitable than spending the long evenings knitting sweaters.

It has taken them some time, but now the most remote island in the world seems to have come fully round to opening its arms to the world’s immense traveling community, just as the people of Paris and Bangkok and Lima and London have done before them. That community is still swelling exponentially, and alarmingly: the 45 million Chinese who toured the world last year, for example, are expected by Beijing to reach 100 million by 2020.

The 275 islanders far off in the South Atlantic may share the hope that among those thousands who eventually throng to have their picture taken beside the famous Edinburgh signboard, there will be few tourists as thoughtless as I. But they shouldn’t count on it.