The Vehicle of Language

Poetry invites us to take an imaginative journey: from the flatness of practical language into the rhythms and sound systems of poetic speech.

By Billy Collins

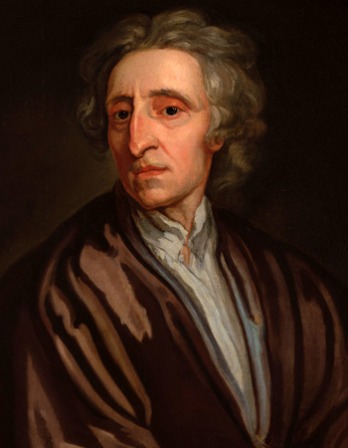

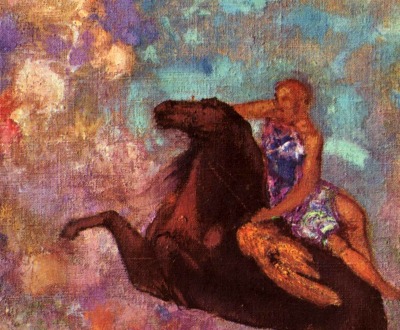

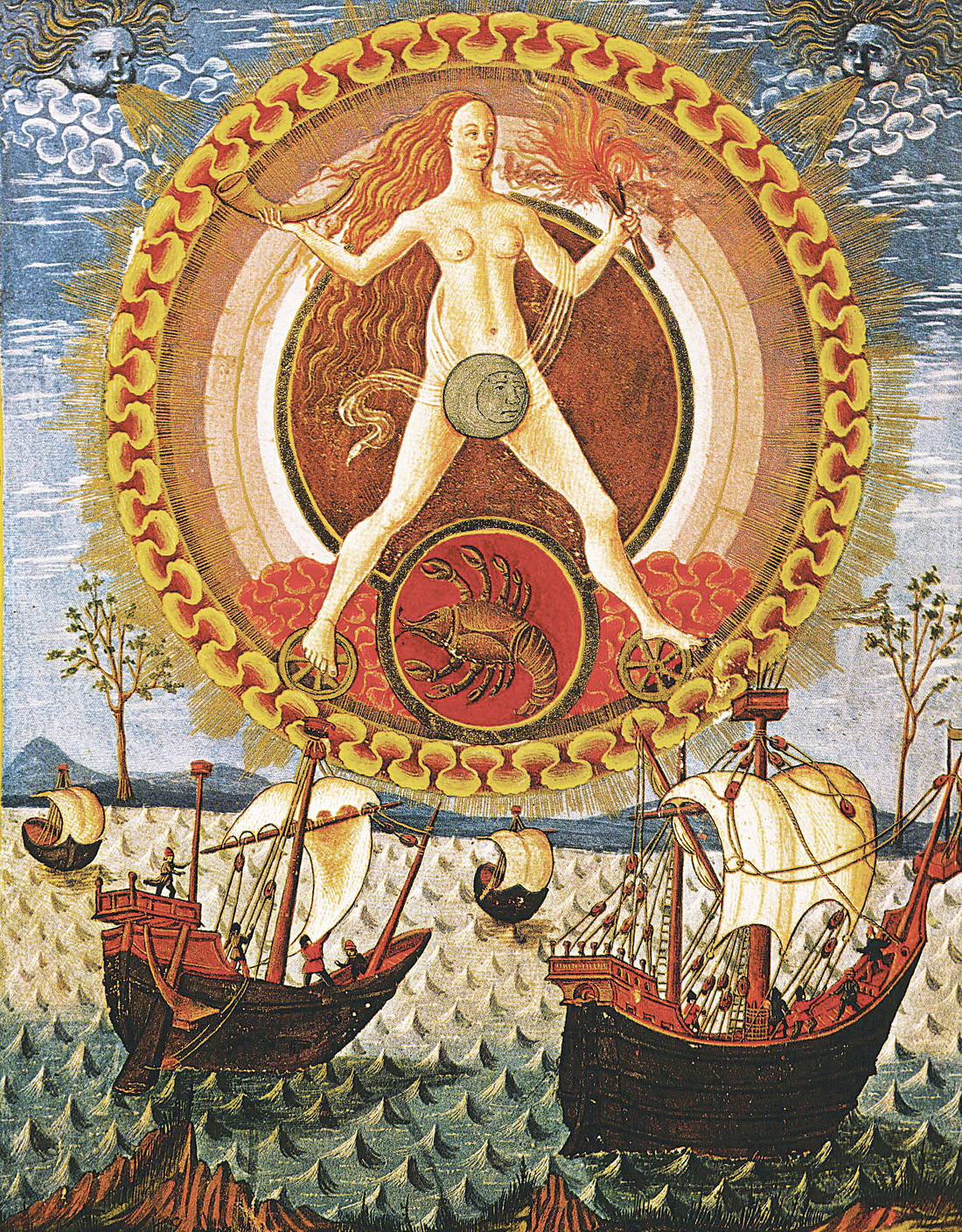

Muse on Pegasus, by Odilon Redon, c. 1900. Private Collection, Paris.

For any teacher of poetry with the slightest interest in reducing the often high-pitched level of student anxiety, one step would be to substitute for the nagging and ultimately pointless question, “What does this poem mean?” the more manageable question “Where does this poem go?” Tracking the ways a poem moves from beginning to end puts the emphasis on the poem’s tendency to travel imaginatively and thus to carry the reader in the vehicle of its language. Instead of asking what Matthew Arnold was “trying to say” in “Dover Beach”—as if he had failed—let us follow the poem’s steps as it finds its way from the tranquility of its beginning, “The sea is calm tonight,” to its climactic vision of the world as a frightening battlefield, a “darkling plain / Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, / Where ignorant armies clash by night.”

The imaginative journey of a good poem is the result of many contrivances ranging from rhetorical modulations to leaps of fanciful conjuring and sudden shifts in time and space—the kinds of hops that

Emily Dickinson may indicate with the dash. The point can be extended to suggest that these maneuvers are really what distinguish poetry from other forms of literary expression. A negative way to account for the unrivaled degree of imaginative freedom in poetry is to point out its exemption from both the rules of nonfiction, which would include—a reader would hope—logic, credibility, sequence, even research, as well as the rules that guide traditional fiction such as plot development, verisimilitude, consistency of character, and the like. Poetry—thank the poetry gods—is not obliged to show how a character goes about overcoming a set of obstacles to achieve a worthwhile goal, to echo a standard definition of the story.

The moon accompanies ships sailing under the sign of Cancer, from a manuscript of De Sphaera, fifteenth century. Biblioteca Estense, Modena, Italy.

The front of the classroom was where I first got interested in the notion of travel as a point of insertion in discussions of poetry. Students found it less intimidating to observe the various moves a poem makes as it journeys from its opening to its close than to reduce the poem to a thematic paraphrase, the kind that allows us to throw away the poem itself and get on with the rest of our lives. To view a poem as a journey brings us closer to the way the poet experienced the poem as it was composed, that is, as a series of maneuvers, the zigging and zagging of the poem’s progress, its tacking into the wind of an uncooperative diction to get where it must go. The poem is not a code of meaning, but a navigation from the gambit of its opening lines to the destination that was unknown but there all along. It is typical for contemporary poets to say that they don’t know where they are going when they begin a poem. The claim rests on the belief in spontaneity, as if anything were purely possible in the act of composing. But the consensus is that knowing where the poem is headed amounts to a degree of calculation that, given the romance of the immediate, dooms the effort to failure. The poet should begin by not knowing much, and he or she will profit, in the phrasing of William Matthews, by maintaining the benefits of their ignorance for as long as possible. Foreknowledge eliminates the possibility of surprise. As Robert Frost said, no surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader. An interesting question is how a poet can plan for surprise. You can’t cover your eyes with your hands and then ask, “Guess who?”

William Butler Yeats recognizes the vital importance of a sense of travel and surprise in poetry when he distinguishes between poems written by the will and poems written by the imagination. In a poem written by the will, the poet knows where he is going and flaunts his determination to get there. Here is an example of the approach—chosen almost at random by flipping through an anthology—called “Long Island Sound,” written by Emma Lazarus, the poet who put the famous inscription on the Statue of Liberty:

I see it as it looked one afternoon

In August,—by a fresh soft breeze o’erblown.

The swiftness of the tide, the light thereon,

A far-off sail, white as a crescent moon.

The shining waters with pale currents strewn,

The quiet fishing smacks, the Eastern cove,

The semicircle of its dark, green grove.

The luminous grasses, and the merry sun

In the grave sky; the sparkle far and wide,

Laughter of unseen children, cheerful chirp

Of crickets, and low lisp of rippling tide,

Light summer clouds fantastical as sleep

Changing unnoted while I gazed thereon.

All these fair sounds and sights I made my own.

You have heard of the man who mistook his wife for a hat? This poet has mistaken a body of water for a Christmas tree. Take all the nouns from the poem—breeze, tide, sail, moon, waters, currents, cove, sun, sky, children, crickets, cloud (which is kind of an impressionistic poem in itself)—and line them up on one side of the page; then take all the modifiers—fresh, soft, far-off, shining, pale, quiet, luminous, merry, cheerful—and line them up on the opposite side of the page. You have the makings of a good gang war, a rumble, the Sharks and the Jets, the Crips and the Bloods, the Adjectives and the Nouns. The smart money is on the Nouns.

But more to the point, the poem ends pretty much where it began only with a gesture toward lassoing all the images into the circle of the poet’s self. Lazarus’ poem reminds me of Oscar Wilde’s seemingly flip comment that, “All bad poetry springs from genuine feeling.” We have to be careful to notice that he is not saying that all poetry based on genuine feeling is bad. He is saying that the authors of bad poetry are invariably sincere. Poems like Lazarus’ carry the burden of their subject and intention from beginning to end. They cleave to the topic with the fidelity of a lawyer, composing a kind of poetry that is purposeful, heartfelt, and driven by purity of intention, but they fail to go anywhere and thus leave readers in the same place where they began. They fail to capitalize on the imaginative slipperiness and unpredictability of poetry. Such poems may be compared to a plane that takes off from Miami and, some time later, lands in Miami.

The poem that travels light, travels furthest. That is to say, for the poetic traveler, subject matter is at best provisional, a gate of departure, a thing to be jettisoned like horses in the horse latitudes, if the poem is to move. The subject of a poem is always its least original aspect. Willa Cather said about fiction that there are only a handful of human stories, but we keep telling and retelling them so desperately, it’s as if they had never been told before. And William Matthews only half facetiously pointed out that there are really only four subjects for lyric poetry:

1. I went out into the woods today and it made me feel, you know, sort of religious.

2. We’re not getting any younger.

3. It sure is cold and lonely (a) without you, honey, or (b) with you, honey.

4. Sadness seems but the other side of the coin of happiness, and vice versa, and in any case the coin is too soon spent, and on we know not what.

One poem of mine (come on, it was only a matter of time), called “Theme,” touches on the subject of poetry’s limited subject matters:

It’s a sunny weekday in early May

and after a ham sandwich

and a cold bottle of beer on the brick terrace,I am consumed by the wish

to add something

to one of the ancient themes—youth dancing with his eyes closed,

for example,

in the shadows of corruption and death,or the rise and fall of illustrious men

strapped to the turning

wheel of mischance and disaster.There is a slight breeze,

just enough to bend

the yellow tulips on their stems,but that hardly helps me

echo the longing for immortality

despite the roaring juggernaut of time,or the painful motif

of Nature’s cyclical return

versus man’s blind rush to the grave.I could loosen my shirt

and lie down in the soft grass,

sweet now after its first cutting,but that would not produce

a record of the pursuit

of the moth of eternal beautyor the despondency that attends

the eventual dribble

of the once gurgling fountain of creativity.So, as far as the great topics go,

that seems to leave only

the fall from exuberant maturityinto sudden, headlong decline—

a subject that fills me with silence

and leaves me with no choicebut to spend the rest of the day

sniffing the jasmine vine

and surrendering to the ivory governanceof the piano by picking out

with my index finger

the melody notes of “Easy to Love,”a song in which Cole Porter expresses,

with put-on nonchalance,

the hopelessness of a lovebrimming with desire

and a hunger for affection,

but met only and always with frosty disregard.

Poetry that wishes to surprise can often be seen looking for a way to shed its subject for another more compelling one, or, even better, to transcend subject matter entirely so that the poem enters a realm where neither writer nor reader can quite say what the poem is now “about.” Such poems take up where prose ends, and are worthy of the name poetry because they begin at the point where the possibilities of prose become exhausted. The only thing such poems are about is their own saying.

Here is a poem called “The Owl,” by Edward Thomas, a man whom Robert Frost considered his only friend, which makes a simple but startling maneuver:

Downhill I came, hungry, and yet not starved;

Cold, yet had heat within me that was proof

Against the North wind; tired, yet so that rest

Had seemed the sweetest thing under a roof.Then at the inn I had food, fire, and rest,

Knowing how hungry, cold, and tired was I.

All of the night was quite barred out except

An owl’s cry, a most melancholy cry

Shaken out long and clear upon the hill

No merry note, nor cause of merriment,

But one telling me plain what I escaped

And others could not, that night, as in I went.And salted was my food, and my repose,

Salted and sobered, too, by the bird’s voice

Speaking for all who lay under the stars,

Soldiers and poor, unable to rejoice.

The poem goes from the speaker’s deprivations—his hunger, coldness, and fatigue—to their alleviations—food, warmth, and rest—that the inn provides the traveler. But the poem also moves from the outdoors to the indoors and then back out again. From solitary winter travel, to the warmth of an inn, then, triggered by the incidental owl’s cry, back out again to a broader view of “all who lay under the stars, / Soldiers and poor, unable to rejoice.” The poem was written in 1915, so the soldiers are literally the infantry of World War I, but for us they are the soldiers of today and today’s homeless. This kind of three-part movement from A to B and back to A is a characteristic of many poems, and basic to the drama of the major Romantic lyrics of William Wordsworth and

Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Typically, these poems open with a speaker in an outdoor setting observing his surroundings. Something triggers a reverie and the speaker moves from the landscape inward to his own mind. Finally, he returns to the present scene, as if roused from a dream, and the landscape he now revisits is altered by the mood of his meditation.

For a poem that involves a more complex and more audacious set of maneuvers, here is “The Long Meadow” by Vijay Seshadri. It moves from the grand to the ordinary, here from the mythic to the personal, and it does so suddenly, even jarringly:

Near the end of one of the old poems, the son of righteousness,

the source of virtue and civility,

on whose back the kingdom is carried

as on the back of the tortoise the earth is carried,

passes into the next world.

The wood is dark. The wood is dark,

and on the other side of the wood the sea is shallow, warm, endless.

In and around it, there is no threat of life—

so little is the atmosphere charged with possibility that

he might as well be wading through a flooded basement.

He wades for what seems like forever,

and never stops to rest in the shade of the metal rain trees

springing out of the water at fixed intervals.

Time, though endless, is also short,

so he wades on, until he walks out of the sea and into the mountains,

where he burns on the windward slopes and freezes in the valleys.

After unendurable struggles,

he finally arrives at the celestial realm.

The god waits there for him. The god invites him to enter.

But, looking through the glowing portal,

he sees on that happy plain not those he thinks wait eagerly for him—

his beloved, his brothers, his companions in war and exile,

all long since dead and gone—

but, sitting pretty and enjoying the gorgeous sunset,

his cousin and bitter enemy, the cause of that war, that exile,

whose arrogance and vicious indolence plunged the world into grief.

The god informs him that, yes, those he loved have been carried down

the river of fire. Their thirst for justice

offended the cosmic powers, who are jealous of justice.

In their place in the celestial realm, called Alaukika in the ancient texts,

the breaker of faith is now glorified.

He, at least, acted in keeping with his nature.

Who has not felt a little of the despair the son of righteousness now feels,

staring wildly around him?

The god watches, not without compassion and a certain wonder.

This is the final illusion,

the one to which all the others lead.

He has to pierce through it himself, without divine assistance.

He will take a long time about it,

with only his dog to keep him company,

the mongrel dog, celebrated down the millennia,

who has waded with him,

shivered and burned with him,

and never abandoned him to his loneliness.

That dog bears a slight resemblance to my dog,

a skinny, restless, needy, overprotective mutt,

who was rescued from a crack house by Suzanne.

On weekends, and when I can shake free during the week,

I take her to the Long Meadow, in Prospect Park, where dogs

are allowed off the leash in the early morning.

She’s gray-muzzled and old now, but you can’t tell that by the way she runs.

From the vaguely mythological world of “one of the old poems,” we slip briefly into the unheroic present with its “flooded basement.” But then the poem gains altitude as it delivers its hero to a “celestial realm” where this “son of righteousness” must face a final test with only his dog for company. A single word is sometimes enough to turn a poem in a new direction, and here the lowly word “dog” rings a note of ordinariness that swings the poem toward its final destination, the charming, pedestrian final scene of the poet taking his elderly dog for an outing in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. All the high talk of myth and ancient drama, which may bring to mind the hero stories of Joseph Campbell, is abruptly replaced by the relaxed, colloquial voice (“when I can shake free”) of the contemporary speaker who downshifts the poem from the interaction of gods and heroes to the earthly immediacies of Suzanne and the aging mongrel, and the crack house where she was found.

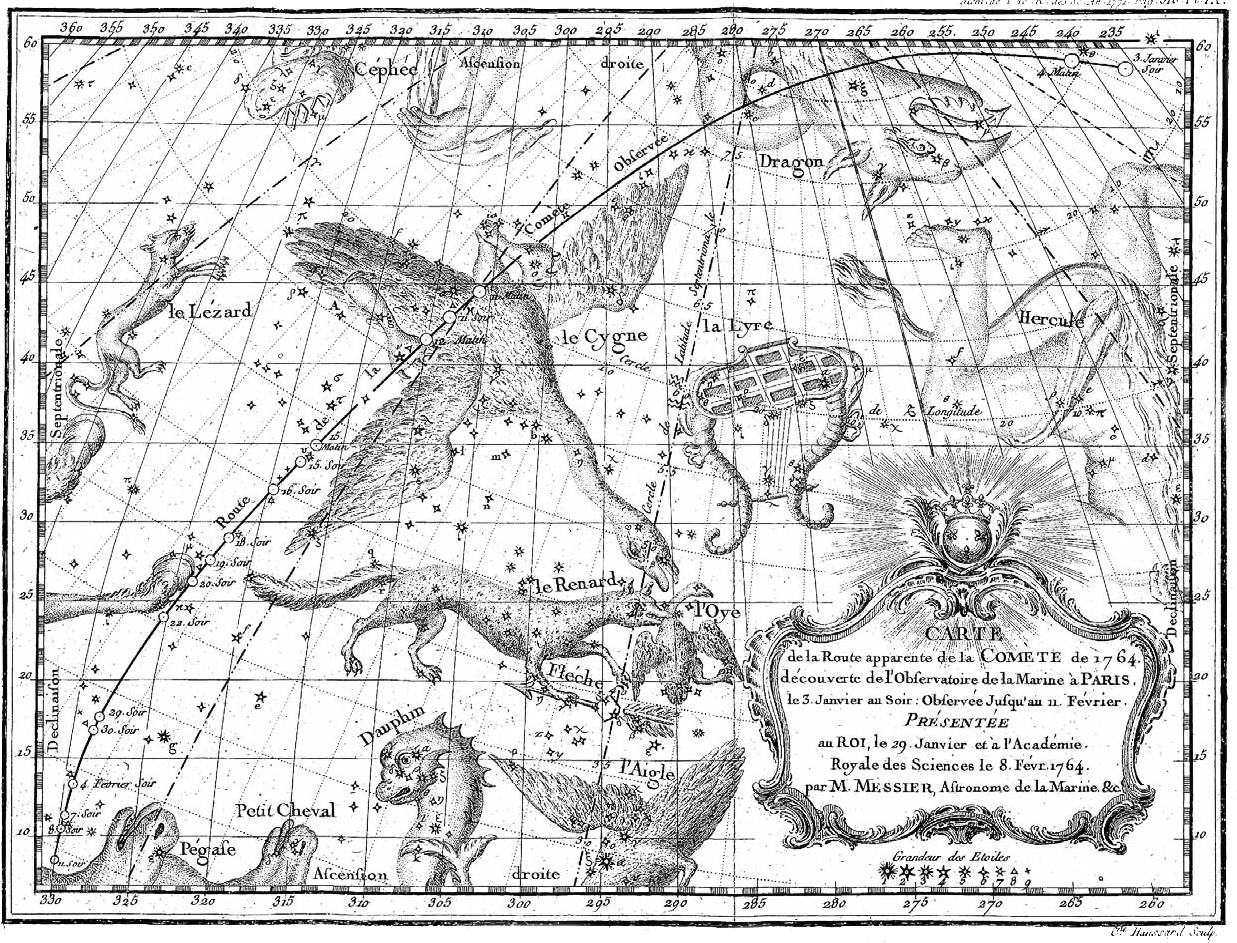

Star chart with the route of the 1764 comet, by Charles Messier, 1764.

This kind of “turn”—in Italian, la volta—has become a recognizable feature of contemporary lyric poetry. The first poetic form which virtually institutionalized the “turn” by making it an essential rule was the sonnet. Whether in its Italian or English format, the sonnet falls into two parts; to oversimplify, the first part says something and the second part reflects on the first part. It is as if after eight or twelve lines, the poet becomes stricken with self-consciousness and feels compelled to comment on what he just said. Perhaps it is no accident that the high-water mark of the sonnet occurred in the Renaissance when such concepts as individuality and authorship were just being foregrounded. Since then, much to the benefit of poetry’s readers and practitioners, the kinds of swervings that poems may execute have grown increasingly complex.

The Greek poet Yannis Ritsos strikes me as a verbal sleight-of-hand artist, who has an uncanny ability to find an invisible seam in his own poem and slip through it into a new dimension. One way he does this is by switching the terms of the comparison on which a metaphor or simile is based. After introducing an illuminating comparison, he sometimes becomes more interested in the secondary B term than the primary A term, more taken with the rose itself, say, than in its use in clarifying the subject of love. His short poem “Miniature” begins in a simple domestic setting but ends in a most unusual region:

The woman stood up in front of the table. Her sad hands

begin to cut thin slices of lemon for tea

like yellow wheels for a very small carriage

made for a child’s fairy tale. The young officer sitting opposite

is buried in the old armchair. He doesn’t look at her.

He lights up his cigarette. His hand holding the match trembles,

throwing light on his tender chin and the teacup’s handle. The clock

holds its heartbeat for a moment. Something has been postponed.

The moment has gone. It’s too late now. Let’s drink our tea.

Is it possible, then, for death to come in that kind of carriage?

To pass by and go away? And only this carriage to remain,

with its little yellow wheels of lemon

parked for so many years on a side street with unlit lamps,

and then a small song, a little mist, and then nothing?

This poem always leaves me blinking in wonderment. The final word “nothing” has the effect of making the rest of the poem vanish into thin air. Here we witness poetry’s fondness for slipping into the mysterious, but the way Ritsos does this is no mystery. The poem’s opening little scene of the woman and the soldier contains a simile. The slices of lemon are likened to the wheels of a tiny carriage. To this day, I cannot slice a lemon without thinking of this little carriage, just as every time I see a dogwood petal I think of Elizabeth Bishop’s image of each looking as if it had been burned at the tip with a cigarette. At the outset, the poem has the feeling of a story, but the story is interrupted by a series of abrupt, disturbing statements (“Something has been postponed. / The moment has gone. It’s too late now.”). Something unfathomable but irrevocable has occurred, and the resulting disequilibrium sets up the poem’s crucial shift: the carriage, originally just the subordinate part of a simile, becomes somehow real and thus replaces the initial subject of the poem. The tenor (the lemon) and the vehicle (the carriage) trade places and by this reversal of terms, the poet slips us into a purely literary dimension, yet one that seems as real as the poem’s opening scene of a woman and a soldier. The metaphor of the carriage becomes a kind of verbal hologram: the reader can walk inside of it but cannot feel the walls. The carriage is promoted from an attendant simile to the new subject of the poem with its new setting—a misty, dark street where a little song is silenced and all that is left is nothing. The reader leaves the poem and enters the “child’s fairy tale,” only now it is for adults.

By developing a disproportionate interest in some aspect of itself, the Ritsos poem manages to lose sight of its purported subject. Richard Hugo calls this the movement of a poem from its “triggering subject” to its “generated subject.” According to him, the poem should not know what its real interests are until it gets underway. The poem’s true subject is discovered, not preconceived.

Poetry invites us to travel into new realms: from the flatness of practical language into the rhythms and sound systems of poetic speech. More pointedly, from the degraded mass language of corporations, politics, and advertising into intimate speech. Poetry also invites us to enter its physical shape, for unlike prose, poetry does not fill the space of a page but rather occupies it the way sculpture occupies three-dimensional space. If prose is a continuation of noise, poetry is an interruption of silence, and the white space that surrounds the poem is a visual sign of that silence. Insofar as it is the only history we have of the human heart, poetry can carry us into the history of feeling and connect us to that largest of communities. But for me, the most direct, almost visceral, experience of travel provided by poetry arises from those conceptual and imaginative shifts and turns that push the poem off course into new fields of wonder and surprise. John Ashbery, one of the most surprising verbal travelers of our age, deserves the last word: “I think that in the process of writing, all kinds of unexpected things happen that shift the poet away from his plan, and that these accidents are really what we mean when we talk about poetry.”