Unexemplary words and unfounded doctrines are avoided by the noble person. Why utter them?

—Dong Zhongshu, 120 BCIn the Panthéon

History is written by the victors. So, too, in the world of ideas. Phillipp Blom on a group of thinkers far more daring than those enshrined in the Panthéon.

By Philipp Blom

Panoramic view of the interior of the Panthéon in Paris, photograph by Jean-Pierre Lavoie, 2005.

The metropolitan jungle breeds strange animals, none stranger perhaps than the UX in Paris, a group dedicated to preserving culture in subterranean fashion. For several years, members of the secretive organization ran clandestine cinemas and held parties in catacombs and disused Metro stations, but their crowning glory was a feat of “guerilla restoration.” Without the knowledge of authorities, a guerilla team called Untergunther expertly gained access to the Panthéon, one of the most important monuments of the French capital, and during hundreds of hours of nocturnal work, restored the nineteenth-century Wagner clock—which had not functioned for four decades. When the repairs were completed in 2006, they notified the Panthéon’s dumbfounded administrator.

The Panthéon is sacred ground in Paris—not because it was built as a place to worship the Almighty, but because the French revolutionaries turned it into a site for the burial and commemoration of, as the facade proclaims, the grands hommes of the nation. Rising high above the Latin Quarter and illuminated at night by fiery orange lights, the building with its imposing cupola stands also as an object lesson in the pitfalls of national memory and the challenges of writing history.

The Panthéon was built originally as the church of St. Geneviève after Louis XV had sworn to honor her should he recover from a grave illness. Because of the exorbitant costs of financing the monarch’s will and whim, construction was finished only in 1791. Meanwhile, the Revolution happened. The church was designated a mausoleum for the nation’s great men, the first of which, the count of Mirabeau, was admitted in 1791, only to be excluded three years later, when political allegiances had changed. History also is subject to changing administrations.

Since then the Panthéon has been the theater of many ideological battles, the center of consecration of the French sense of self and its many permutations. Félix Éboué, a member of the colonial administration, became the first black Frenchman to enter into the hallowed ground, in 1949; the first woman, Marie Curie, in 1995. The tomb listing reads like the greatest hits of French intellectual history—Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, André Malraux, Émile Zola. The most famous philosophers interred in the crypt are two stars of Enlightenment thought: Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who were thus honored already during the eighteenth century—despite the fact that the former spent his adult life in exile and the latter was not even French. Tourists often pose for photographs in front of their sarcophagi.

As with any compilation, it is as interesting to learn who did not make the cut as those who did. Denis Diderot, a contemporary of Rousseau, was repeatedly denied the honor—last in 1913, when the French Parliament voted against his panthéonization (you have to love the French for having words like this). As editor of the Encyclopédie and author of fiction, plays, and essays, Diderot was crucial to the spreading of the Enlightenment and the ideas that would lead to the Revolution. He is recognized as a great writer, but the nation’s highest elected body nevertheless cold-shouldered him. He was, and still is, thought to be ideologically unreliable, a little too risqué—too interested in philosophical ideas for a great literary man, too literary for a true philosopher.

His friend Baron Paul-Henri Thiry d’Holbach, a pioneer of secularism with many works to his name, welcomed into his salon the most brilliant minds of his age. Writing under pseudonyms, d’Holbach published book after book—among them Christianity Unveiled (1761) and The System of Nature (1770)—in which he spread the message of a radical Enlightenment and the possibility of a just and democratic world, despite the fact that the expression of such opinions was still subject to years of imprisonment or public execution. Diderot and d’Holbach showed courage as well as intellectual acuity. They are model citizens. Their bones, however, lie scattered and unidentified, in the ossuary of a little-known church on the Right Bank, the Church of Saint-Roch, in a parish that specialized at the time in burying men of doubtful reputation.

What makes memory so highly contested and the craft of the historian so fraught is often not a disagreement about facts. It is easy (at least in principle) to point out that something thought to be true is actually a construct—that, for example, we know William Tecumseh Sherman never wrote the words, “War is hell,” or that Patrick Henry never shouted, “If this be treason, make the most of it!” The most intractable memory wars take place over the purpose of the narrative constructed out of agreed-upon facts and about the values underlying those choices.

It is still common in Russia to describe Josef Stalin as a great statesman and to view the millions he had arrested, tortured, shot at dawn, starved to death, and sent to die in the Gulag as regrettable but acceptable collateral damage in the march toward a brighter future. Historians who hold this view do not dispute that he killed untold numbers of victims; they just believe that the mass killing of civilians can be good or at least necessary under certain circumstances. Chairman Mao, Pol Pot, and the Nazis thought the same, as did Napoleon Bonaparte and Julius Caesar.

Interior of a London coffeehouse, c. 1700.

Conflicting accounts of the past are shaped around cultural values and then congeal in communal memory. We know who we are because we know where we come from—or at least we think we do. Memory binds together families and communities and forms the soil in which the understanding of the present grows. It is essentially poetic, focusing its gaze on emblematic moments of the past, iconic images of identity and culture frozen in time, and cleansed of contradiction, of complexity and context.

The best history, I believe, attempts to counter this tendency by reconstructing the past before it was cast in amber, revealing its life cycles and contingency. Like the guerilla restoration practiced by Untergunther, it is a concerted effort to restore what has long been broken and has not received attention from the authorities—or has received the wrong kind of attention and has been amended so that the original is unrecognizable.

The task is crucial in a democratic society, because unchallenged myths end up informing not only personal perceptions but also political and collective decisions. They may have their origin in a fiction of sorts, but they pickle memory and shape reality. Around the turn of the eighteenth century, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe—bolstered by the earlier efforts of classical enthusiasts like Johann Winckelmann—created and popularized visions of nobility, guiltless sensuality, and bravery symbolized by ancient Greece. The poets’ resplendently pure version of antiquity became the inspiration for works of historicist architecture and art (the U.S. Capitol, Monticello); the study of Greek language and civilization from idealizing textbooks informed the sensibilities of writers and politicians; Byron even traveled to Greece to fight for Greek independence and recalled the past, “I dream’d that Greece might still be free;/For standing on the Persians’ grave,/I could not deem myself a slave.” The speeches by Pericles and Homer’s heroes still rang in the ears of French, German, and British officers called up in World War I. Restorers even “cleaned” vividly polychromic paint from statues and buildings, thus reinforcing this created idea of classical purity. How different ancient Greece may have been is still being discovered, and will be rediscovered in the light of every generation’s preoccupations and fears.

The source material needn’t even be that old or distant in order to become pliant in the hands of a poet. Friedrich von Schiller further enthused readers moved by eighteenth-century Romanticism and nationalism with his story of the heroic struggle of the sixteenth-century Spanish prince Don Carlos against his tyrannical father Philip II. We know Don Carlos through Schiller’s highly effective play as a noble young man fighting repression, a moving story that Giuseppe Verdi used as inspiration for his eponymous opera. Both Schiller and Verdi were invested in the fight for emancipation of their own countries. The fact that the historical Don Carlos was the mentally unstable and physically infirm result of centuries of Habsburg incest whose fits of rage and rampant sadism were infamous and who was locked up not because of his passion for liberty and free thought but because he had flogged a horse to death and threatened to murder his father is less well known. The idealized young man was a more resonant idea for the romantic sensibilities of Italians and Germans, and for a long time, Schiller’s creation usurped historical reality.

For the tourists posing in front of the graves of the great, the Panthéon is the face of French history, a history written in marble and inscribed in gold, complete with key terms and the names of men to be memorized. Memory co-opts the past to serve the interests of the present, and the dominant interpretation of a collective past becomes the story we tell about ourselves. In this case, it has decided for the moderates who were assimilated into the interests of the powerful and against the radicals and their more difficult message. This official history has been reinforced in books and classrooms, making intellectual gods of Voltaire, Immanuel Kant, and Rousseau. Diderot and d’Holbach, on the other hand, have lost the posthumous battle for public memory.

In their own day they were revered and reviled in equal measure, much visited and written about. D’Holbach’s famous salon could assemble on a single evening luminaries such as Diderot, David Hume (known then primarily as a historian, not as philosopher), the economist and anti-colonialist Guillaume Raynal, the novelist Laurence Sterne, historian Edward Gibbon, and Cesare Beccaria, the Italian legal reformer and opponent of the death penalty. The salon was not a philosophical school with rigid teachings but an ongoing conversation between scientists and poets, atheists and believers, philosophers and practitioners. Called “the personal enemy of God,” d’Holbach invited priests and other critics to his table and even kept a chaplain at his summer house, to say mass for his conventionally minded mother-in-law.

The radical enlighteners were well connected, but more importantly, their frighteningly radical writings were read and discussed throughout the Western world; The System of Nature, d’Holbach’s materialist masterwork, was on the Church’s List of Forbidden Books and had to be printed and distributed in secret. It still sold more than a hundred thousand copies during the second half of the eighteenth century. Condemned by the Church and hated by the Court, d’Holbach and Diderot were beacons of free-thinking and directly inspired America’s founders. Franklin is likely to have participated at the dinners and ensuing discussions; Jefferson read and admired Diderot, d’Holbach, Helvétius, and Raynal, as well as their intellectual predecessors (their works are still in his library). For the Declaration of Independence, he transformed the Lockean formulation for the pursuit of life, health, liberty, and possessions into the more properly Epicurean and Diderotean “pursuit of happiness.”

Their relative obscurity is not an unsolvable mystery if one compares their thinking to that of Voltaire and Rousseau, who criticized absolutist excess but not the authoritarian rule of the few over the many; they attacked the Church but sung the praises of the “highest being”; their views were solidly deist and authoritarian and lent themselves to justifying the power of a new, post-Revolutionary politics. Robespierre made Rousseau the patron saint of the new state, heaped him with praise, and had a bust of him carved from a stone taken from the Bastille.

D’Holbach and Diderot had a very different vision of human nature. Enthusiastic followers of their century’s tidal wave of new scientific discoveries, they decided that nature was evolved, not created; that it was all material and had no place for immortal souls; that it consisted of nothing but matter and that we are animals within it, a universe empty of sense and without God. In the oppressively clerical environment of their day, this last point took a good deal of their attention. In sharp polemics they attacked Christianity and religious faith in general, arguing that it was nothing but a primitive fiction designed to keep the poor in their place, a conspiracy of magistrates and priests.

Diderot and d’Holbach saw the truest and the highest goal of human nature not in reason, but in lust. Humanity’s existence is driven by lust, by Eros, by the search for pleasure. This sensualist approach had an important metaphysical consequence: in a world without sin, a world in which no suffering and wrathful God who has condemned all lust and demands suffering from his creatures on this earth in order to soften the blow of eternal punishment, the goal of life becomes the best possible realization of pleasure, the education of desire in accordance with natural laws. In a society without transcendental interference, this chance, the chance of the pursuit of happiness, must be given to all.

These views were ideological ipecac to just about everyone who sought to maintain or gain power, from the aristocracy to Revolutionary dictators such as Maximilien de Robespierre and Napoleon, all the way up to the Bourbon Restoration that followed. “Men will not be free until the last king is strangled with the guts of the last priest,” wrote Diderot—not the kind of message to appeal to the nineteenth-century bourgeoisie. Laissez-faire capitalism allowed a self-proclaimed Christian middle class to profit from the misery of the working poor, at home and in the colonies. They could not argue for their position with Diderot, who became ever more scathing about the justification of power, privilege, slavery, and colonial expansion. It was Voltaire’s moderate Enlightenment that offered them the necessary vocabulary and allowed them to see themselves as the guardians of civilization, Enlightenment, and religious values, put above the ignorant masses by divine providence.

The radical enlighteners had analyzed the emergent power structure. Their thought was evolutionist long before Charles Darwin; they defended the rights of slaves before William Wilberforce and of women before Mary Wollstonecraft. They wanted to see individual fulfillment in a morality built around lust and social justice in a society built on pleasure and free choice, not on pain and oppression. Their potent ideas were unsurprisingly intoxicating discoveries for latter-day revolutionaries; among d’Holbach and Diderot’s ardent readers were Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Sigmund Freud.

Censorship, condemnations, and the threat of arrest had been a fact of life for many of the guests at d’Holbach’s table, but they could not anticipate the cruel or unusual punishment that they might suffer after their deaths. The twisting of facts and relationships began as Voltaire and Rousseau were ceremonially laid to rest in the Panthéon and eulogized as the noblest minds of humanity. Forgotten were Voltaire’s political cabals, his role as creditor to the very potentates he apparently attacked, his highly ambivalent stance to the aristocrats who kept him rich and famous, and his cynical stance to religion as opium for the masses. Forgotten were Rousseau’s tantrums and his betrayal of friends, his tolerance of dictatorship. Two sarcophagi and countless busts and embossed books broadcast their grandeur and unimpeachable probity.

At the same time Diderot and d’Holbach have been denounced as immoral, ridiculed as talentless, kept out of some school syllabuses; their bones moldered in an anonymous heap, their books were printed only sporadically and in small editions. When spoken of, Diderot was softened into an eccentrically Gallic novelist and editor of a long-outdated encyclopedia, and d’Holbach was relegated to the status of a dim and boring precursor of Marxist theory. The salon and its guests were quickly forgotten: the Parisian house where for twenty-five years Europe’s most brilliant minds—“Sheiks of the Rue Royale,” Hume called them—met and debated still bears no plaque or visible recognition of any kind.

The grand narrative of a rationalist Enlightenment that freed humanity from superstition only to subjugate it once again, this time to the dictates of reason and rationalization, suited the interests and self-image of an economy driven by entrepreneurship and fueled by a cult of efficiency and cheap labor. We have inherited the truncated history and repeated it to one another, tacitly encouraging a narrowness of thought that bears little resemblance to one of the freewheeling exchanges over candlelight at d’Holbach’s salon.

Stalin had photographs originally showing him with murdered rivals edited, the offending figures removed—a commissar vanished here, Leon Trotsky disappeared there. Normally history does not go to such exacting trouble. The existence of a second, more radical Enlightenment tradition is not denied completely, but two centuries of historical bias have done their work, slowly but surely.

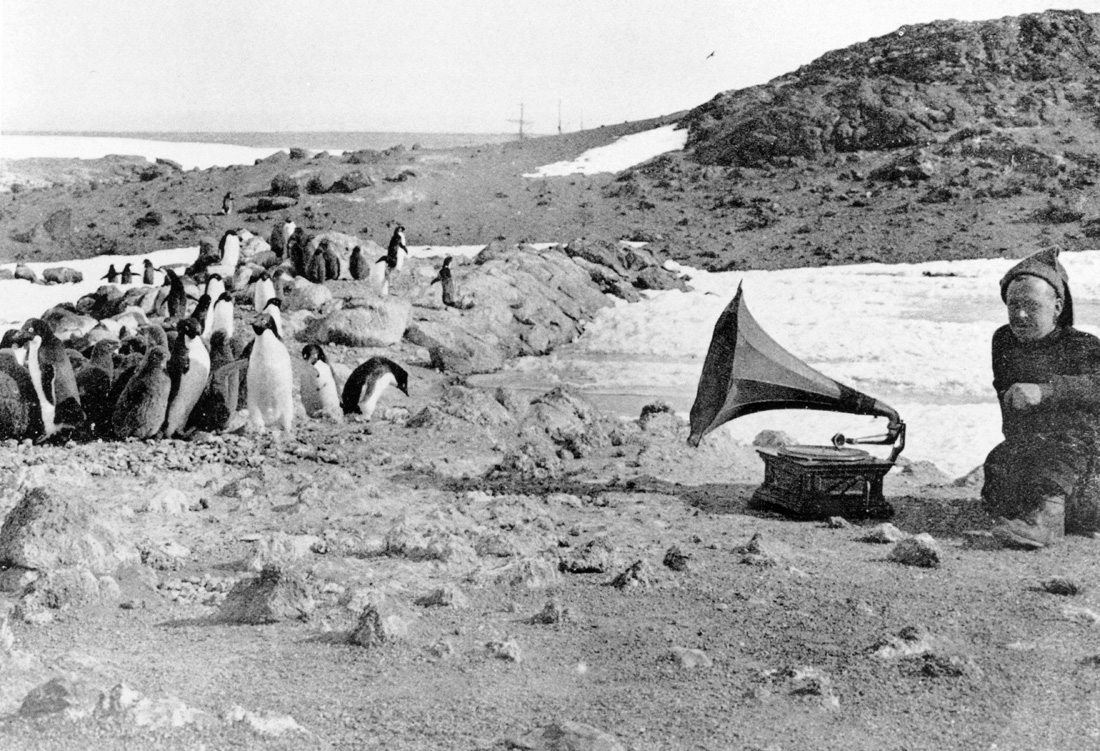

Penguins listening to a gramophone during Ernest Shackleton’s expedition to Anartica, 1907. The Bridgeman Art Library.

As interpreters, historians have more in common with musicians than with poets like Schiller. A historian faces the same challenges as a pianist: Ludwig van Beethoven, for example, was in the habit of putting exact metronomic markings above his pieces, and a musical fundamentalist would have solid ground on which to stand when claiming that this is exactly as fast as they ought to be played. But we have different instruments today requiring different techniques, and Beethoven himself, who ruined many a piano in his quest for more sound, might have preferred the weighty sound possibilities of a modern concert grand, or the power of a modern orchestra. Concert halls today are larger than any he ever heard his music played in; some are too resonant for playing as fast as he indicated because the music would turn into an acoustic blur, while the dry sound of a small room or a studio may demand a higher speed and therefore also a different phrasing. Musician and audience, finally, live in a world after Wagner, Brahms, Schönberg, Cage, the Beatles and the Stones—a myriad of associations and resonances that the composer and his contemporaries did not share. How then is it possible to mediate any kind of truth between Beethoven’s intent and today’s ears?

A musician is inevitably left with the task of translating the factual basis—the music, the score—into the reality of living art in a particular setting. Even in the best of circumstances, the result is not going to be the one truth about a work by Beethoven but one interpretation that may or may not be accepted by listeners because they find it fascinating, illuminating, and authoritative. The score in itself is dead and can be brought to life only as a subjective account informed by knowledge, craft, taste, circumstance, and personal style. The result is always mired in perspective, in a particular horizon, but that is not to say that it is arbitrary. It is always contingent, but not relativist in a postmodern way: it is based on facts in a score and relies on stylistic conventions, technical competence, and experience—and ultimately it must resonate with perceptions of the audience. An interpretation that obviously ignores pertinent facts will not be accepted by those who know them; but things can still be seen very differently, as illustrated not only by the debate about the relative merits of Voltaire and Diderot, but also when we ask whether Stalin was a great visionary hero or a monstrous criminal.

We have an anthropological need for narrative, call it a storytelling gene, which allows us to orient ourselves, to survive psychologically in a chaotic and manifestly unjust world in which good people suffer and criminals appear to live happily, children die of diseases, striving and gifted people are crushed while others callously succeed. Lived experience rarely allows us to assume that our actions have the intended result, and it would be unbearable without stories that impose order and meaning on experience, even if it flies in the face of the facts.

During World War II, young bomber crews looked up to the crews who had flown many dangerous missions and admired their experience, which had carried them safely home time and again. Later, researchers found that there was no statistical evidence that experience contributed to survival rates among bomber crews. Those who survived longest were simply lucky, and their luck reinforced the illusion of their invulnerability. For their comrades, however, it was essential to believe in their experience, in the idea that every mission completed made it more likely that they would live. It was the story they needed for their survival.

We could not project ourselves into the future, could not plan and hope without stories; we make life seem logical by telling stories about it. They project meaning and purpose into the world and for a few moments they lend beginning, middle, and end, catastrophe and catharsis, to the otherwise futile and overwhelming driftwood of experience. The stories we tell ourselves not only serve as existential consolation, they also determine who we are, how we act, which goals we pursue.

The narrative of the moderate Enlightenment still holds us in its thrall; even if it comes with its own constrictions in the way it makes us see ourselves. It is a story valuing the rulers over the ruled, men over women, mind over body, the “civilized” over the “savage.” It served a purpose and its proponents have become prophets. Successive generations of French writers and politicians have invested in this convenient memory and its monuments, history has been carved in stone and it looks as if it is there to stay.

Every man has a right to utter what he thinks truth, and every other man has a right to knock him down for it. Martyrdom is the test.

—Samuel Johnson, 1780It is ironic that Diderot himself regarded his posthumous reputation as his highest good (“the heaven of atheists” as he wrote), especially because he knew about the nature and the challenges of our need for stories. In his own novels, he never allows the reader to forget that she is reading a tale, that the narrator can intervene and hold the reader hostage: “You can see, reader,” the author warns at the very beginning of Jacques the Fatalist and his Master, “… it depends only on me to make you wait one year, two years, three years, for the tale of Jacques’ loves; I can separate him from his master and make him encounter all the hazards I like. What stops me from marrying the master off and making him a cuckold?”

The novelist is boss, the novel is his vehicle, and the reader’s longing to immerse herself in the story becomes an intricate game of expectation and power, of suspension of disbelief and constructive skepticism. Diderot knew that stories are necessary to our understanding and survival in the world, but that they are and remain just stories, a conspiracy to be entered into at one level, but analyzed at another in a constant dialectical motion.

In doing so, Diderot described the role of a good historian, and perhaps even a recipe for living a life of intellectual richness. That alone would have been reason enough to enshrine him in the Panthéon. But then he was never a systematic thinker, and his best work must be searched in the least formal contexts. Many of his best insights are written in offhand remarks and they unfold slowly in the minds of his readers. The most gregarious of men, he is still an author with few but fervent readers. Somehow, the invisibility of his remains in the ossuary of the obscure Saint-Roch Church suits him. Perhaps the French guerrilla restorers will one day burrow their way into his final resting place and arrange his bones in a more dignified way—secretly, they may already have done so.