The drunken man is a living corpse.

—St. John Chrysostom, 390Crashing the Party

Late night at the symposium.

Socrates’ speech finished to loud applause. Meanwhile, Aristophanes was trying to make himself heard over their cheers in order to make a response to something Socrates had said about his own speech. Then, all of a sudden, there was even more noise. A large drunken party had arrived at the courtyard door and they were rattling it loudly, accompanied by the shrieks of some flute girl they had brought along. Agathon at that point called to his slaves, “Go see who it is. If it’s people we know, invite them in. If not, tell them the party’s over, and we’re about to turn in.”

A moment later they heard Alcibiades shouting in the courtyard, very drunk and very loud. He wanted to know where Agathon was; he demanded to see Agathon at once. Actually, he was half carried into the house by the flute girl and by some other companions of his, but at the door he managed to stand by himself, crowned with a beautiful wreath of violets and ivy and ribbons in his hair.

“Good evening, gentlemen. I’m plastered,” he announced. “May I join your party? Or should I crown Agathon with this wreath—which is all I came to do, anyway—and make myself scarce? I really couldn’t make it yesterday,” he continued, “but nothing could stop me tonight! See, I’m wearing the garland myself. I want this crown to come directly from my head to the head that belongs, I don’t mind saying, to the cleverest and best-looking man in town. Ah, you laugh; you think I’m drunk! Fine, go ahead—I know I’m right anyway. Well, what do you say? May I join you on these terms? Will you have a drink with me or not?”

Naturally they all made a big fuss. They implored him to join them, they begged him to take a seat, and Agathon called him to his side. So Alcibiades, again with the help of his friends, approached Agathon. At the same time, he kept trying to take his ribbons off so that he could crown Agathon with them, but all he succeeded in doing was to push them farther down his head until they finally slipped over his eyes. What with the ivy and all, he didn’t see Socrates, who had made room for him on the couch as soon as he saw him. So Alcibiades sat down between Socrates and Agathon, and as soon as he did so, he put his arms around Agathon, kissed him, and placed the ribbons on his head.

Agathon asked his slaves to take Alcibiades’ sandals off. “We can all three fit on my couch,” he said.

“What a good idea!” Alcibiades replied. “But wait a moment! Who’s the third?”

As he said this, he turned around, and it was only then that he saw Socrates. No sooner had he seen him than he leaped up and cried, “Good god, what’s going on here? It’s Socrates! You’ve trapped me again! You always do this to me—all of a sudden you’ll turn up out of nowhere where I least expect you! Well, what do you want now? Why did you choose this particular couch? Why aren’t you with Aristophanes or anyone else we could tease you about? But no, you figured out a way to find a place next to the most handsome man in the room.”

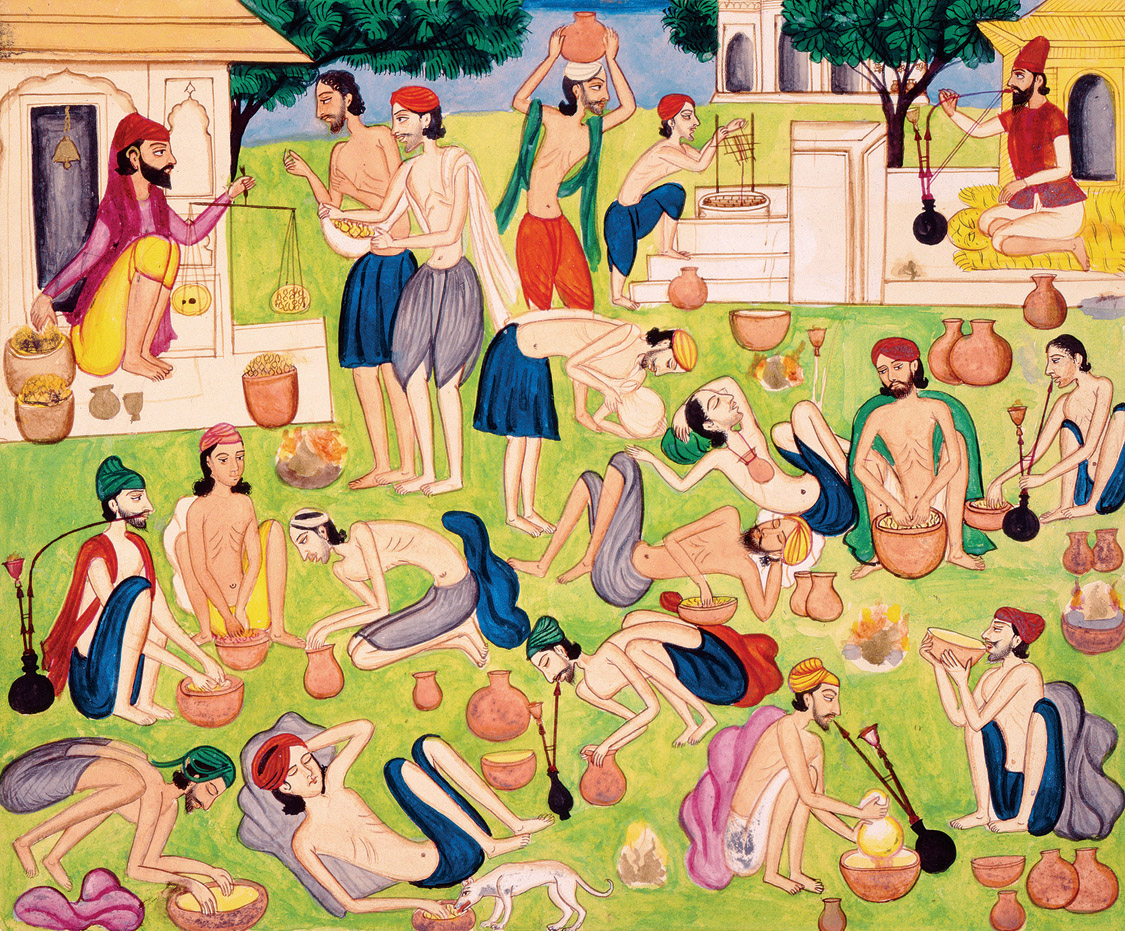

Depiction of the manufacturing and use of narcotics, Punjab, India, c. 1870. © British Library Board. Bridgeman Images.

“I beg you, Agathon,” Socrates said, “protect me from this man! You can’t imagine what it’s like to be in love with him: from the very first moment he realized how I felt about him, he hasn’t allowed me to say two words to anybody else—what am I saying, I can’t so much as look at an attractive man but he flies into a fit of jealous rage. He yells, he threatens, he can hardly keep from slapping me around! Please, try to keep him under control. Could you perhaps make him forgive me? And if you can’t, if he gets violent, will you defend me? The fierceness of his passion terrifies me!”

“I shall never forgive you!” Alcibiades cried. “I promise you, you’ll pay for this! But for the moment,” he said, turning to Agathon, “give me some of these ribbons. I’d better make a wreath for him as well—look at that magnificent head! Otherwise, I know, he’ll make a scene. He’ll be grumbling that, though I crowned you for your first victory, I didn’t honor him even though he has never lost an argument in his life.”

So Alcibiades took the ribbons, arranged them on Socrates’ head, and lay back on the couch. Immediately, however, he started up again, “Friends, you look sober to me; we can’t have that! Let’s have a drink! Remember our agreement? We need a master of ceremonies; who should it be?…Well, at least till you are all too drunk to care, I elect…myself! Who else? Agathon, I want the largest cup around…No! Wait! You! Bring me that cooling jar over there!”

He’d seen the cooling jar, and he realized it could hold more than two quarts of wine. He had the slaves fill it to the brim, drained it, and ordered them to fill it up again for Socrates.

“Not that the trick will have any effect on him,” he told the group. “Socrates will drink whatever you put in front of him, but no one yet has seen him drunk.”

The slave filled the jar, and while Socrates was drinking, Eryximachus said to Alcibiades, “This is certainly most improper. We cannot simply pour the wine down our throats in silence: we must have some conversation, or at least a song. What we are doing now is hardly civilized.”

What Alcibiades said to him was this:

“O Eryximachus, best possible son to the best possible, the most temperate father: hi!”

“Greetings to you, too,” Eryximachus replied. “Now what do you suggest we do?”

“Whatever you say. Ours to obey you, ‘For a medical mind is worth a million others.’ Please prescribe what you think fit.”

“Listen to me,” Eryximachus said. “Earlier this evening we decided to use this occasion to offer a series of encomiums on Love. We all took our turn—in good order, from left to right—and gave our speeches, each according to his ability. You are the only one not to have spoken yet, though, if I may say so, you have certainly drunk your share. It’s only proper, therefore, that you take your turn now. After you have spoken, you can decide on a topic for Socrates, on your right; he can then do the same for the man to his right, and we can go around the table once again.”

“Well said, O Eryximachus,” Alcibiades replied. “But do you really think it’s fair to put my drunken ramblings next to your sober orations? And anyway, my dear fellow, I hope you didn’t believe a single word Socrates said: the truth is just the opposite! He’s the one who will most surely beat me up if I dare praise anyone else in his presence—even a god!”

Plato

From “The Symposium.” Plato composed this long dialog about a drinking party some time after 386 bc, but the dramatic date is one year before Athens launched the disastrous Sicilian expedition, a large-scale naval offensive against Syracuse that Alcibiades had proposed. On the eve of setting sail, he was accused of drunkenly defacing a number of the stone statues called herms, was then tried in absentia, and sentenced to death. He defected to Sparta, which defeated Athens in the Peloponnesian War in 404 bc. Socrates was put to death five years later.